Things have been quiet here for quite a while – mostly because I’ve been inundated with work (always a good thing). But I have also recently joined the party eight years late to the Twitter train. For daily images of cool insects please follow me over there @skepticalmoth. Of course some stories require a longer format to discuss, and I will continue to do so occasionally here – not to mention I will always keep my reference and technique pages up to date. Thank you!

|

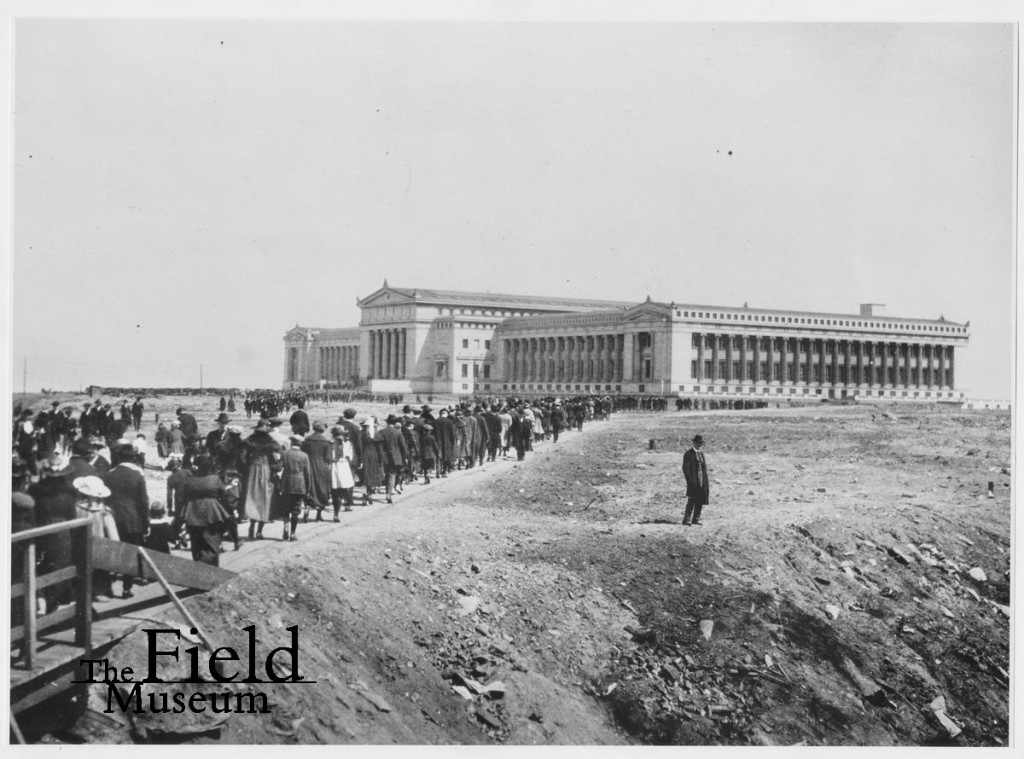

As I was photographing and databsing the Cicindelinae from the collections of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science I came across this specimen collected on the 10th June 1921, Chicago Illinois. The beetle is Cicindela hirticollis hirticollis (could be a boldly marked ssp rhodensis as they readily intergrade along their boundaries) and is one of the most wide-spread species of tiger beetle we have in the US – so this isn’t what caught my eye. As a native Chicagoan and former Field Museum employee, 1921 sounded like a familiar date. I quickly Googled and found the reason why. Summer 1921 was the grand opening of the Field Museum’s new (and still current) location in Grant Park. This famous photograph by Charles Carpenter illustrates just how popular the museum was on opening day, May 2, 1921. The collector of the specimen is unknown and only left a label in their vintage tiny handwriting. We have the specimen here in Denver so the collector was likely not a native Chicagoan (those specimens would have ended up at the Field Museum or even the Smithsonian). I suspect, or at least like to imagine, that our beetle was collected by an amateur Entomologist while he was in Chicago for the opening of the new museum. The Denver Museum of Nature & Science (at the time Denver Museum of Natural History) was only 21 years old at this point in history, but nevertheless an equally popular if not smaller version of the opulent Field Museum. Our collections hold the majority of Edward B. Andrews Rocky Mountain collection from the 1930’s, so perhaps I can wildly speculate that this was one of his earlier specimens collected on a pilgrimage east.

This beautiful animal is a moth I reared from Quercus palmeri down in the Chiricahua Mountains of Arizona. It’s in the family Gracillariidae and most likely in the genus Acrocercops – according to Dave Wagner it may represent a new species, but that’s not an uncommon thing with small moths. It was fairly abundant, so the short series I have will probably remain in the Denver Museum until someone would like to work on the alpha taxonomy of the group (or the day comes when I actually don’t have manuscripts piling up). Finding a caterpillar mining a leaf in the wild and rearing it at home is one of the most rewarding things you can do as a naturalist. Charley Eiseman over on Bug Tracks does this all the time (and illustrates it beautifully) – not only do you end up with a beautiful specimen, but the host plant and often parasitoids are all recorded in this process. Have you seen the beautiful photos taken by Sam Droege for the USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab? Ever wondered how he got those beautiful shots? Tomorrow, September 26th at 1pm eastern time, Sam will be doing a LIVE tutorial on YouTube on how to take these photos and how to do it on your equipment! Go to the YouTube channel and a live feed should pop up as soon as they are online. It should be fascinating!

http://www.youtube.com/USGSI’m excited to be participating this year as an instructor for the Lepidoptera Course at the Southwestern Research Station near Portal, Arizona. I’ll be one of eight other instructors who will provide a hands on and intense 9-day long course on the collection, preservation and identification of Lepidoptera. I really can’t imagine a better way to learn about moths and butterflies than in a setting like the Chiricahua Mountains during the peak of the monsoons. Reservations are still open! Take a moment to go check out the Lepidoptera Course website, and browse talks from past years. I’ll encourage you to attend and hope to see you in a few weeks! I came across this short article today claiming that this recent description of the hairstreak butterfly, Ministrymon janevicroy Glassberg 2013, may in fact be the “last truly distinctive butterfly species left to be discovered in the United States…. [and] the era of new U.S. butterfly species is ending”. I find that statement a little bit odd. One one hand it seems obvious, most of the butterflies in the United States were described long ago. 90% of the hairstreak butterflies were described before 1900 and 97.5% before 2000 (R. Robbins pers. comm.). On the other hand it gives me an itch in the back of my brain that may falsely imply we’ve completed a task and we can move past collecting or research on butterflies. I don’t think the authors intended the latter – and while it’s good to realize we’ve come this far in butterfly taxonomy, it might be helpful to discuss how far we haven’t come (especially when you consider moths!). The paper itself (free from Zookeys above) is great – it very carefully outlines the case to separate these species and I would easily agree with their conclusions. The closest the authors get to saying this is the last butterfly to be described in the US is here at the end of page 14 and onto page 15.

And as it turns out the lines about the last butterfly were from a press release written by the authors (pers. comm.). But to me it sounds like splitting hairs, are these butterflies really that distinct? New butterflies are still being described from the US from less obvious characters as eye color, but often have large differences in the genitalia – and these characters can often be much more distinctive than a color feature that fades in preserved specimens. So, yes, this is perhaps the last species to be found that could be told apart in the field. But if anything it points at how much we need specimens in collections to figure these things out in the first place. The authors used 88 specimens of M. janevicroy and compared them to hundreds of other specimens of other species. Good thing there are collectors working hard in the field to find as many of these butterflies as possible (and often at the time not knowing exactly what they are catching). As lepidopterists look closer at the differences separating many of our more diminutive species new names are created to describe what was once thought to be one larger, wide-ranging, single species. And any readers of my blog should well be aware that many, many moth species are left to be described in the United States. I know of a few revisions that are upcoming that are going to nearly double the size of relatively large families of big and well collected moths – not to mention how little progress we’ve made in the microlepidoptera. One estimate I’ve heard suggests that only 20% of the Tortricidae moth species have been described! When intensive revisions are conducted of these smaller groups the species numbers explode. Go out and collect! The Hop Azure (Celastrina humulus) is a diminutive and uncommon blue found on the front range of the Rockies here in Colorado. Its host plant is the wild hop: Humulus lupulus, varieties of which are of course a critical ingredient in beer! In a week or two I’ll be out in the field looking to photograph this sucker along with the swallowtail Papilio indra indra, hopefully with some luck. And so along comes Robert Schorr who has been intimately aware of this butterfly for years and has wished he had funding to work on it. Robert, being an unparalleled genius, combined two of my favorite things: Lepidoptera and beer. A quick presentation to Odell Brewery based out of Fort Collins, Colorado and voila- Celastrina Saison Ale was born. And of course, $1 of each beer sold will go to Schorr’s research on the Hop Azure butterfly. Genius. Perhaps next up, a beer that supports my research on hop-moths? (there are a few of course!) Better yet the hop-growing industry might be interested in that work… And for the non-beer lovers out there a Saison is a nice and effervescent ale with lots of fruit and spice, but still on the dry end and not very sweet – perfect for drinking on a warm summer day. The time is fast approaching for this years National Moth Week, July 20-28 2013! The first ever Moth Week last year was a huge success with over 300 events from 49 US States and 30 countries! Help make this year even bigger – if you’re interested in moths at all you should find a local event to attend or create one of your own. Public or private, you can participate with a leisurely night where you crack a few beers with friends and watch some moths – or you can invite the public and encourage photography, collecting, and submission of your data! Every event helps to spread the popularity of moths, even if it’s just you in your back yard. I’ll be planning a Moth Week event here in Denver, possibly during the weekend and hopefully at a local State Park. If you can’t travel far out of Denver my colleague David Bettman and I already have a moth-talk scheduled for July 25th at Bluff Lake Park Nature Center which will be followed by a black light sheet (this event will appear separately on the map below). I hope you can join a moth week this year! NMW For this Monday’s Moth I thought I’d post a brief tutorial on how to accurately determine the sex of moths. While there are lots of examples of sexually dimorphic species (where males and females are obviously different), the vast majority of moths are not. Saturniidae make our lives easy by having strikingly different antennae between the sexes. For example you can see the large, plumose antennae of this male Dryocampa rubicunda below. The corresponding females have antennae that are thread-like in comparison. Every time you have two moths with antennae this different then it’s fair to call the larger ones male. Usually these will be Saturniidae, but occasionally some hawk moths, tiger moths, and a scattering of other groups have antennal dimorphism. Most moths out there do not have these obvious differences, or you only have one specimen with no counterpart to compare it to, and so it takes a little more detective work to figure out what sex they are.

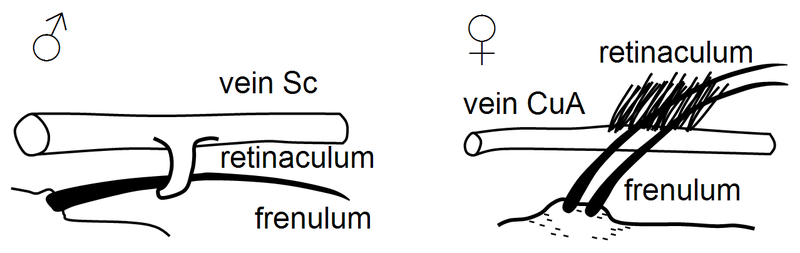

There are two places left to check – the tip of the abdomen and the frenulum under the wings. Male moths have claspers – or spatula like folds of their genitalia that physically grab onto the female while mating. Frequently you can see the outline of these claspers which look like a pair of folded hands on the underside tip of the abdomen. If no split is seen at the tip of the abdomen then it usually is a female. This technique can work well for butterflies since they don’t use a wing-coupling device like a frenulum, but may not be successful in hairy moths where the structure of the abdomen is obscured. Most Lepidoptera have some mechanism for keeping their wings together in flight. Basal orders like the Micropterigidae and Hepialidae have a simple thumb-like process that comes off of the hindwing to help couple the with the forewing. But the vast majority of moths use a frenulum-retinaculum. This illustration from Wikipedia perfectly illustrates the mechanism and the sexual dimorphism. For some unknown reason female moths have multiple smaller bristles while males have a larger single one. Perhaps the multiple bristles provide greater support for an egg-laden female, whereas the single bristle provides more flexibility and power for males. But I don’t believe any hypothesis has ever been tested.

To better illustrate this here is the underside of a male Apamea aurinticolor (Noctuidae) with the frenulum clearly visible on the right. On the left the frenulum is tucked into the retinaculum on the forewing – note this structure is a clump of tightly curled scales on the costa of the forewing – not that patch of hairs that point upwards. The second image is the same moth at a higher magnification with the frenulum colored in green. Sometimes you have to tease out the frenulum from hiding to determine what’s going on – a pin that has been pushed down onto your desk will create a tiny little hook perfect for this job. Occasionally you might break the frenulum, but that’s no major loss if you lose only one and you record the sex on the label.

Here is a female Autographa mappa (Noctuidae) that faintly shows the 3 bristles that make up her retinaculum. Click to embiggen on Flickr. I love digging through the abyssal pit of internet crazy because I get to find gems like this: The Mothman on Mars? Linked in the ‘article’ is a NASA Curiosity rover photo, Mastcam Right. SOL 194. Photo taken on 21 February 2013. The rock they are talking about as “mothman” is in the upper left corner – the triangular one casting a shadow (I added my own arrow). I can’t see it, at all… I see a rock, that looks like a rock and probably flies like a rock. But you’ve got to love crazy anomaly hunting. |

Skepticism |