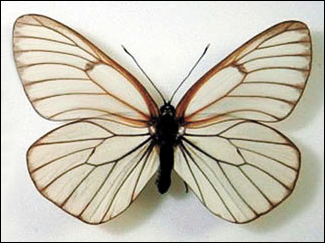

На фота - белы з чорнымі жылкамі (Aporia crataegi ssp), і гэта ёсць у цяперашні час вяртаецца у Карэйскі інстытут біялагічных рэсурсаў. Пазыкі вяртаюцца, як яны павінны быць, кожны дзень – і нават можа налічваць тысячы асобнікаў. У мяне самога ёсць некалькі сотняў месцаў у пазыку ў некалькіх музеях, якія чакаюць даследаванні. Як толькі скончу сваю працу (або запытаць падаўжэнне), узоры неадкладна вяртаюцца разам з маёй паперай. На жаль, гэта не рэдкасць, калі крэдыты выйшлі, і застаўся без дазволу, на працягу дзесяцігоддзяў. Прынамсі, у адным выпадку, наколькі мне вядома (назвы і ўстановы адрэдагаваныя) пазычаныя ўзоры знаходзіліся так доўга, што ўтварылі невялікі міжнародны інцыдэнт. Замежныя амбасадары павінны былі афіцыйна запытаць узоры, якую павінен быў уручыць асабіста наш пасол у іх краіне.

Гэты матылёк, аднак, Я не веру, што гэта была частка пазыкі. Дык чаму ён вяртаецца ў Карэю?

Reading into the article I get the impression that S. Korean researchers are not requesting loan returns, however instead asking for the return of “taken” Korean property.

Korean researchers say this was a unique case – in fact, this is the biggest number of insects to be returned to the country. “We persuaded the Hungarians to return the insect specimens that were taken from Korea by visiting the country twice last year and suggesting we start joint research on the insects,” said expert Oh Kyung-hee at the institute.

I’m a bit confused as to whether this is actually the case or not; perhaps the author has missed the ball on what a “loan” actually is, or perhaps something was lost in translation. But the quote seems to stand on its own. We are all familiar with the trend in the last few years of foreign governments requesting, or demanding in the case of Egyptian antiquities, the return of priceless pieces of cultural heritage. I whole heartedly agree on that matter. Так, the British Museum should return the Parthenon to Greece from whence it was plundered. Так, the mummies of Egyptian kings should be returned to Egypt. These pieces, while they are internationally relevant, are part of a unique cultural history of extant peoples.

Матылькі (all insects and animals), do not fall into the same category as stolen antiquities. Primarily, insects are composed of populations of living animals that can continually be sampled. If Korea would like larger collections of their own insects, then Korean entomologists should be out in the field collecting (I know of some excellent Korean entomologists!). Secondarily, while insects are part of a country’s natural heritage, they were obviously not created or invented by humans – thus they can not be directly owned by the state. Of course that is my own opinion that wouldn’t hold up in court. Аднак, the fact that these insects were either collected during a time where permits did not exist – or they were collected legally under permit – means that new policies or laws should not affect past events. Most permits already have stipulations where you have to leave a certain percentage of everything you collected in the country before you leave. I also highly doubt that anyone would be encouraged to do research in a country that requires 100% of all specimens collected to be returned. That misses the entire point of building collections.

Every country should build and maintain their own scientific collections. One of the strongest reasons for allowing foreign research is to not only further the cause of science on a whole, but to distribute insect specimens globally to assure existence of voucher specimens for perpetuity. There are also secondary benefits of making specimens available to researchers in their home country. Students can come along and have direct access to material that is either too expensive to acquire fresh, or too fragile to ship 10,000 miles.

Human nature tends to lean towards the unstable – war has claimed many museum collections of Poland and Germany (and across Europe as whole). Nature and accidents take care of the rest – на працягу апошняга года значная калекцыя павукоў і змей страчаны ў Сан-Паўлу, Бразілія. Прыкладаў занадта шмат, каб іх пералічыць, і яны ўзыходзяць да страты Александрыйскай бібліятэкі вакол 48 ЕЦБ (які не быў музеем натуральнай гісторыі, але вы зразумелі сутнасць). Яшчэ больш трагічнымі становяцца зборнікі, якія страчаныя з-за занядбанасці. Знакамітая калекцыя чылійскіх двухкрылых тыпаў 19-га стагоддзя амаль уся была страчана дерместидами. Пакуль гэтыя падзеі ашаламляльныя – мы павінны засвоіць важнасць распаўсюджвання нашых ваўчараў як мага шырэй. Калі ў Карэі ёсць мэта размясціць усе ўзоры, калі-небудзь сабраныя з Карэі у Карэя – потым адзін інцыдэнт – сказаць… вайна з Паўночнай Карэяй… можа знішчыць усе вядомыя ўзоры і вярнуць карэйскую навуку на сто гадоў назад.

У мяне ўсё яшчэ застаюцца пытанні. Чаму гэтых асобнікаў ужо няма ў карэйскіх калекцыях. Нават калі яны гэтага не робяць, чаму прасіць усё, а не сінаптычны зборнік? (магчыма, гэта адбылося, але было больш нацыяналістычным). З боку Венгрыі было б ветліва вярнуць некаторыя ўзоры, але мне было б цікава, наколькі палітычнай стала гэтая сітуацыя. Ці пагадзіліся даследчыкі на гэта раней часу? Ці гэта было рашэнне, прынятае дырэктарамі і дэканамі…

Я, напрыклад, моцна спадзяюся, што гэта не тэндэнцыя, якая замацоўваецца. Настроі ў многіх краінах Лацінскай Амерыкі ўжо з'яўляюцца аднымі з строгім скептыцызмам – дазволаў амаль немагчыма сустрэць у першую чаргу. У той час як я магу зразумець пачуццё “гэтыя наша флоры і фауны – трымайцеся далей і дазвольце нам зрабіць працу”, гэта не практычнае рашэнне. The fact remains that science isn’t being done in the countries with the highest biodiversity at a rate fast enough to even approach the rate of habitat loss. While discovering what is in the forest will not help protect it, at least we could rescue the data before it is lost forever.

Perhaps I am naive to hope that science will remain apolitical, but we need to carefully watch the trends before we are all forced to return our international specimens.