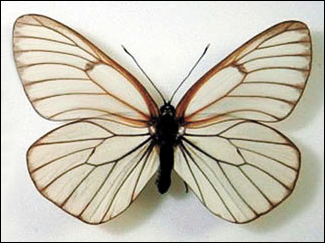

Pictured is a black-veined white (Aporia crataegi ssp), and it is currently being returned to the Korean Institute of Biological Resources. Loans get returned, as they should be, every day – and can even number in the thousands of specimens. I myself have a few hundred moths out on loan from a handful of museums that are pending research. As soon as I finish my work (or request an extension), the specimens are promptly returned accompanying my paper. Unfortunately it is not a rare occurrence where loans have gone out, and remained out without permission, for decades. At least in one case to my knowledge (names and institutions redacted) the loaned specimens were out so long they created a small international incident. Foreign ambassadors had to formally request the specimens, which had to be presented in person by our ambassador to their country.

This butterfly, hala ere, I don’t believe was part of a loan. So why is it going back to Korea?

Reading into the article I get the impression that S. Korean researchers are not requesting loan returns, however instead asking for the return of “taken” Korean property.

Korean researchers say this was a unique case – in fact, this is the biggest number of insects to be returned to the country. “We persuaded the Hungarians to return the insect specimens that were taken from Korea by visiting the country twice last year and suggesting we start joint research on the insects,” said expert Oh Kyung-hee at the institute.

I’m a bit confused as to whether this is actually the case or not; perhaps the author has missed the ball on what a “loan” actually is, or perhaps something was lost in translation. But the quote seems to stand on its own. We are all familiar with the trend in the last few years of foreign governments requesting, or demanding in the case of Egyptian antiquities, the return of priceless pieces of cultural heritage. I whole heartedly agree on that matter. Bai, the British Museum should return the Parthenon to Greece from whence it was plundered. Bai, the mummies of Egyptian kings should be returned to Egypt. These pieces, while they are internationally relevant, are part of a unique cultural history of extant peoples.

Tximeletak (all insects and animals), do not fall into the same category as stolen antiquities. Primarily, insects are composed of populations of living animals that can continually be sampled. If Korea would like larger collections of their own insects, then Korean entomologists should be out in the field collecting (I know of some excellent Korean entomologists!). Secondarily, while insects are part of a country’s natural heritage, they were obviously not created or invented by humans – thus they can not be directly owned by the state. Of course that is my own opinion that wouldn’t hold up in court. Hala ere, the fact that these insects were either collected during a time where permits did not exist – or they were collected legally under permit – means that new policies or laws should not affect past events. Most permits already have stipulations where you have to leave a certain percentage of everything you collected in the country before you leave. I also highly doubt that anyone would be encouraged to do research in a country that requires 100% of all specimens collected to be returned. That misses the entire point of building collections.

Every country should build and maintain their own scientific collections. One of the strongest reasons for allowing foreign research is to not only further the cause of science on a whole, but to distribute insect specimens globally to assure existence of voucher specimens for perpetuity. There are also secondary benefits of making specimens available to researchers in their home country. Students can come along and have direct access to material that is either too expensive to acquire fresh, or too fragile to ship 10,000 miles.

Human nature tends to lean towards the unstable – war has claimed many museum collections of Poland and Germany (and across Europe as whole). Nature and accidents take care of the rest – within the last year a significant collection of spiders and snakes were lost in Sao Paulo, Brasil. Examples are too numerous to list and date back to the loss of the Library of Alexandria around 48 BCE (which wasn’t a natural history museum, but you get the point). Even more tragic are collections that are lost due to neglect. A famous collection of 19th century Chilean Diptera types were almost all lost to dermestids. While these events are jarring – we should learn the importance of distributing our vouchers as widely as possible. If Korea has a goal to house all specimens ever collected from Korea urtean Korea – then one incident – say… a war with North Korea… could wipe out all known specimens and set Korean science back a hundred years.

I am still left with questions. Why don’t these specimens already exist in Korean collections. Even if they don’t, why ask for everything and not a synoptic collection? (perhaps this did happen but was spun to be more nationalistic). It might have been polite of Hungary to return some specimens, but I would be interested in how political this situation became. Did the researchers agree to this ahead of time? Or was it a decision made by directors and deans…

I for one hope strongly that this is not a trend that takes hold. The sentiment in many Latin American countries is already one of closely guarded skepticism – permits are nearly impossible to come across in the first place. While I can understand the feeling of “these are our flora and fauna – keep out and let us do the work”, it is not a practical solution. The fact remains that science isn’t being done in the countries with the highest biodiversity at a rate fast enough to even approach the rate of habitat loss. While discovering what is in the forest will not help protect it, at least we could rescue the data before it is lost forever.

Perhaps I am naive to hope that science will remain apolitical, but we need to carefully watch the trends before we are all forced to return our international specimens.