For this Monday’s Moth I thought I’d post a brief tutorial on how to accurately determine the sex of moths. While there are lots of examples of sexually dimorphic species (where males and females are obviously different), the vast majority of moths are not. Saturniidae make our lives easy by having strikingly different antennae between the sexes. For example you can see the large, plumose antennae of this male Dryocampa rubicunda below. The corresponding females have antennae that are thread-like in comparison. Every time you have two moths with antennae this different then it’s fair to call the larger ones male. Usually these will be Saturniidae, but occasionally some hawk moths, tiger moths, and a scattering of other groups have antennal dimorphism. Most moths out there do not have these obvious differences, or you only have one specimen with no counterpart to compare it to, and so it takes a little more detective work to figure out what sex they are.

There are two places left to check – the tip of the abdomen and the frenulum under the wings. Male moths have claspers – or spatula like folds of their genitalia that physically grab onto the female while mating. Frequently you can see the outline of these claspers which look like a pair of folded hands on the underside tip of the abdomen. If no split is seen at the tip of the abdomen then it usually is a female. This technique can work well for butterflies since they don’t use a wing-coupling device like a frenulum, but may not be successful in hairy moths where the structure of the abdomen is obscured.

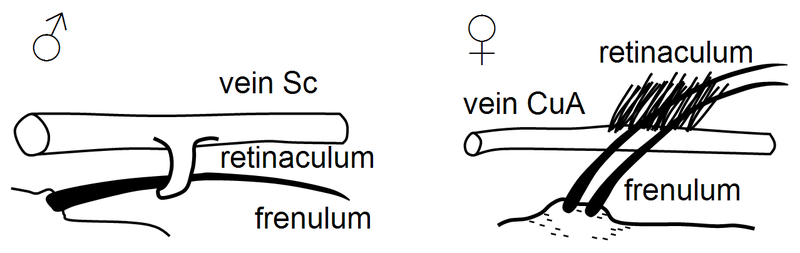

Most Lepidoptera have some mechanism for keeping their wings together in flight. Basal orders like the Micropterigidae and Hepialidae have a simple thumb-like process that comes off of the hindwing to help couple the with the forewing. But the vast majority of moths use a frenulum-retinaculum. This illustration from Wikipedia perfectly illustrates the mechanism and the sexual dimorphism. For some unknown reason female moths have multiple smaller bristles while males have a larger single one. Perhaps the multiple bristles provide greater support for an egg-laden female, whereas the single bristle provides more flexibility and power for males. But I don’t believe any hypothesis has ever been tested.

To better illustrate this here is the underside of a male Apamea aurinticolor (Noctuidae) with the frenulum clearly visible on the right. On the left the frenulum is tucked into the retinaculum on the forewing – note this structure is a clump of tightly curled scales on the costa of the forewing – not that patch of hairs that point upwards. The second image is the same moth at a higher magnification with the frenulum colored in green. Sometimes you have to tease out the frenulum from hiding to determine what’s going on – a pin that has been pushed down onto your desk will create a tiny little hook perfect for this job. Occasionally you might break the frenulum, but that’s no major loss if you lose only one and you record the sex on the label.

Here is a female Autographa mappa (Noctuidae) that faintly shows the 3 bristles that make up her retinaculum. Click to embiggen on Flickr.

We found a gyandromorph L. dispar that retained the dimorphic antennae. Both were “featered”, but the female side had a thicker antenna shaft.