Par Chris Grinter, on July 1st, 2010 And now for the even more infrequently reoccurring series, vox populi! For those without scarring high school memories of latin class (through no fault of my teacher) I’ll bring you up to speed – the title roughly translates to “voice of the people”. Here is another old e-mail that I’ve been saving. It is a 100% real message, but of course I have redacted the real names and addresses to protect the innocent. Enjoy! I also highly encourage submissions of your own-

Winter 2008:

“Salut, I’m so glad I found you. Maintenant, I hope you can help me. 1982, while camping at an old gold mining camp in the Mendocino National Forest I was bitten by a large brown spider. It took three days for the venom to pass through my system. On day three I was 95% blind, the bite swelled to a large grotesquely deep red bump on my arm. I’ll never forget the 12 hours the venom attacked me. The price I payed to survive this spiders venom was…….to loose absolutely all my body fat. I spoke with a doctor from Santa Rosa by phone from a friends place in (some small CA town). He knew about this spider and couldn’t believe I suvived the venom when I told him I lost all my body fat. He also told me it was impossible for someone to survive loosing all their body fat in 12 heures. I reminded him that this was an impossible situation. He told me that this spider is being kept from the public. I believe this spider came from China or Russia. These spiders don’t share anything with other Cali spiders. They have big bodies and short stout legs. The female that bit me was about 4 inch’s and, had 5 males. Four years later, while living in the Hayward hills, I couldn’t believe my eyes, running across the floor, another one. This spider was about 6 inch’s. I know these spiders don’t climb walls or spin webs. They build nest’s, and obtain 4-5 males to protect her and find food. The female never leave’s the nest except…………when a larger female drives her out and, kills her males. This is when people are bitten by this spider, as she runs around looking for another nest. Bites are very uncommon. I wondered………….how big was the female that drove that 6 inch from her nest. Et………….how big do they get. Can I find this spider on display at (your museum)? Is it possible to find all the information their is on this very dangerous spider?”

Continue reading Vox Populi, volume II

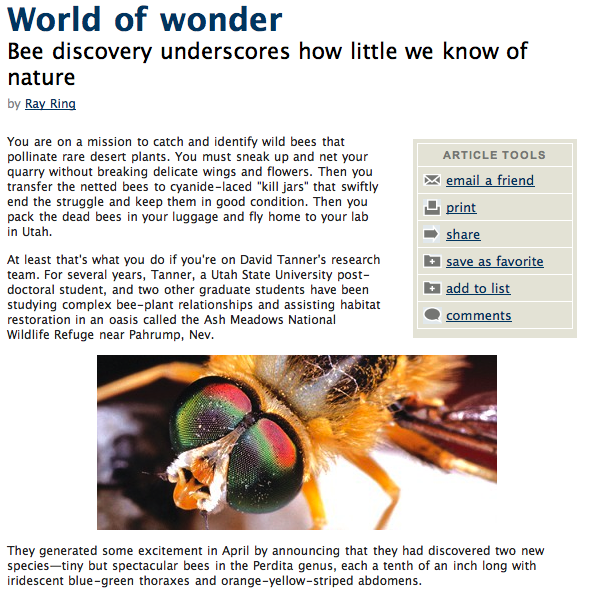

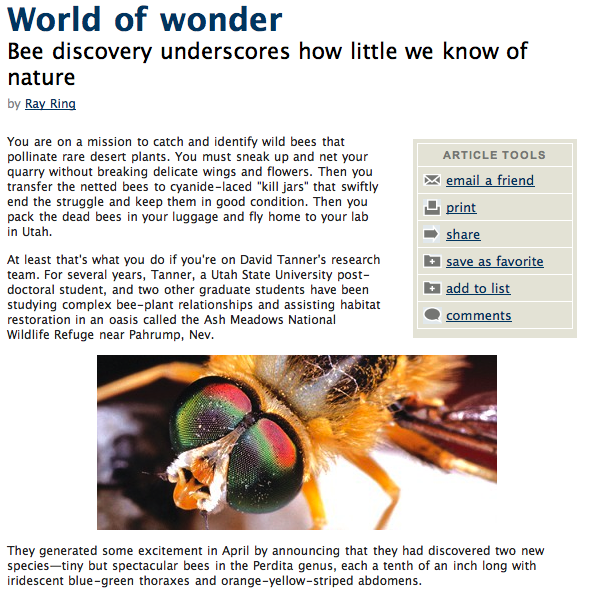

Par Chris Grinter, on June 26th, 2010 Welcome to volume eight of the inconsistently reoccurring series, Génie de la presse. I came across Cet article recently regarding an endemic Puerto Rican butterfly. Who can tell me exactly why this report is misleading? It may be a little trickier than the standard GOP (I suggest discarding any previously associated acronyms with those letters). Hint, just telling me the butterfly in the picture is from Malaysia is not the answer I’m looking for!

Par Chris Grinter, on June 23rd, 2010

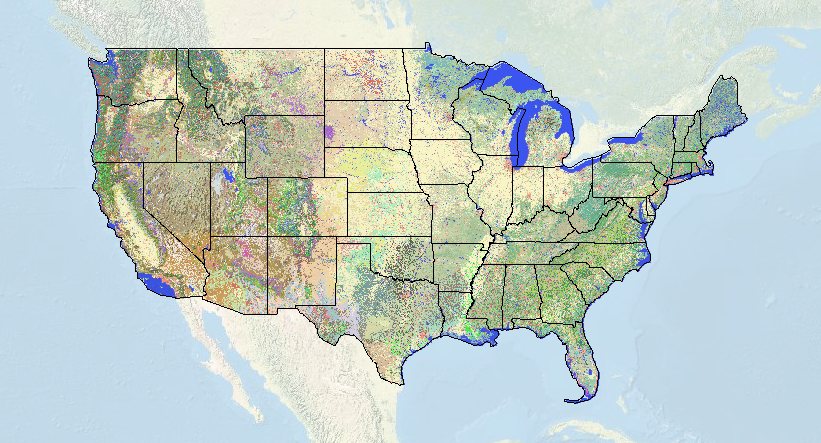

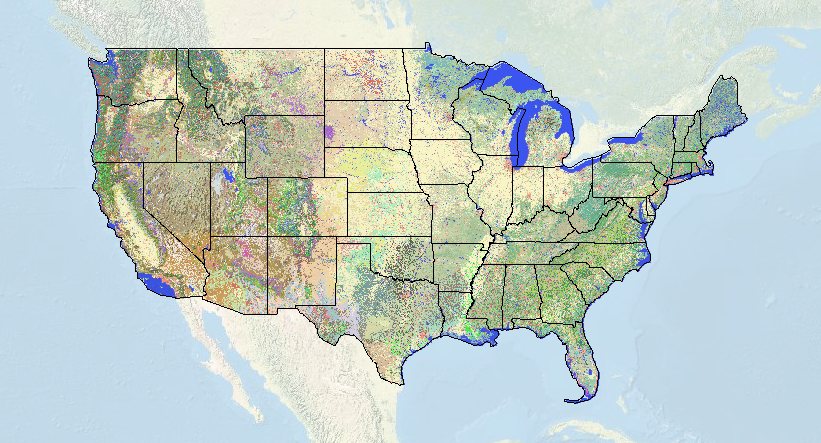

I’ve always wondered how to find the correct terminology for land cover in a given area. Usually, I just ballpark something along the lines of “oak chaparral”. But now I can use this awesome new map brought to us by the USGS/National Biological Information Infrastructure. The level of detail is amazing, and you can specify the degree of accuracy with a drop down tab (1-3). Now with a high-def US topo map I can see exactly where the largest stands of monterrey pine are (actually it’s a California Coastal Closed-Cone Conifer Forest and Woodland) so I can optimally place my trap this weekend.

Continue reading Landscape Cover Map

Par Chris Grinter, le 18 Juin, 2010

Bienvenue à The Moth and Me #12, et mon blog premier carnaval. Malgré les blogs pendant quelques mois, je ne ai pas encore de jeter un regard en arrière et réfléchir sur exactement comment je suis devenu amoureux de lépidoptères en premier lieu. En souvenir d'un temps ou endroit où cela se est passé est impossible, et comme beaucoup de mes collègues et je suis sûr que beaucoup de mes lecteurs, Je ai eu un filet à papillons et “cage à insectes” dans la main dès que je pouvais marcher. Quand il se agit à l'entomologie, je crois presque tout le monde tombe amoureux au premier avec une grande et frappante insectes. Pour moi, ce était un papillon, naturellement. Je me souviens de regarder pendant des heures interminables à la diversité des Ornithoptera et Papilio illustré à Paul Smart de célèbre livre. Quelque part le long du chemin dans la poursuite de quelque chose de nouveau je ai commencé à se aventurer dans le monde nocturne. Mites constituent la majorité de la diversité des lépidoptères; alors qu'il ya près 11,000 espèces aux Etats-Unis, seulement quelques centaines sont des papillons. Cela a ouvert rapidement une porte (peut-être dans un abîme…) à l'abondance choquante trouve partout autour de nous. Cette diversité étonnante a maintenant attiré moi profondément dans la biologie et l'histoire évolutive des lépidoptères. La modification de ces quatorze contributions de papillon blogging ensemble, je ne peux pas me empêcher de réfléchir sur une partie de mon propre voyage de mothing.

Peut-être si je étais un enfant en Europe ce papillon (Déilephila Elpénor porcelet) aurait été le premier à attirer mon attention. Plus à Urban mites Ron Laughton a découvert la diversité étonnante dans sa propre arrière-cour de la même manière que je ne ai grandi ici aux États-Unis. Jetez un oeil à des types de pièges, il a été utilise, dont la plupart il se construit. Un des meilleurs comportements de papillons de nuit est leur volonté de plonger tête baissée dans la lumière. Pas trop loin de Ron, Mike Beale a été blogging papillons britanniques ainsi. Il peut être assez incroyable à quel point nos deux faunes similaires sont (quelques papillons en fait sont le même).

Continue reading The Moth and Me #12

Par Chris Grinter, on June 11th, 2010

This moth is just about as rare as its paranormal namesake (except that it’s real) – it’s a Gazoryctra sp. in the family Hepialidae. They represent a basal lineage of the Lepidoptera and are commonly known as ghost moths or swift moths. Ghost – because males of some species are known to fly in true leks, where they hover up and down in grassy clearings at dusk while females observe. These same males also call for females with pheromones, a bit of a backward situation with insects. Swift- rather self evident, but boreal species have been known to be powerful flyers.

One of the features that help indicate this as a basal lineage is the placement of the wings on the body, some wing venation, reduced or absent mouthparts and the lack of a strong wing coupling device. These moths have a “jugum”, which is a small thumb like projection from the top of the hindwing. Other lineages of moths have a tight coupling mechanism known as the frenulum and retinaculum, where bristles hook the two wings together so they remain coupled during flight. When at rest the jugum folds around and probably helps keep the wings together – but not while in flight; the forewing is out of sync with the hindwing and flight is not dynamic (Scoble 1992).

In the Americas Hepialid biology is very poorly understood. Only a handful of life histories are described globally – all of which seem to be endophagous (boring) in plant root systems. Some early instar larvae may feed in the leaf litter or underground on the root system before entering the rhizome. Australia is fortunate to have a diverse and impressive fauna of Hepialidae – many are brilliantly colored and enormous (250mm or up to 12 pouces!), and a bit better studied. Some larvae are even common enough that aboriginal tribes have used them as a staple food source.

But back to this moth in particular. I collected it in my black light trap last August up in the Sierra Nevada around 10,500 pieds. The species is unknown, and may likely be new. The most frustrating part is that it is the only specimen known to science. The entire genus is very rare, except for one or two commoner species, only a few dozen specimens exist. So is it a female of a species described only from a male? A freakish aberration of an otherwise known species? Or maybe it is actually new. I’ve barcoded the DNA, that actually tells me nothing since there are zero sequences from any closely related species. En fait, as far as I know, the other species in the Sierra haven’t even been collected in decades so I can’t even get a sequence from an older specimen. The icing on the cake is their behavior. They rarely, si jamais, come to light – which may be a result of their crepuscular flight. On the right night they may be on the wing for 20-30 procès-verbal, usually a female searching out a male, or a female flying to oviposit (likely just broadcast scatter their eggs on the ground). So come this late August I’ll be returning to the high Sierra with a few volunteers from the entomology department in hopes of seeing one whiz by me on the steep slopes. If I get some more, it might turn out to be impressive new species for California.

Par Chris Grinter, on June 11th, 2010 Who can see what’s wrong with Cet article?

Par Chris Grinter, on June 9th, 2010

This recent article in the American Naturalist has taken a second look at some of the famously inflated species estimates, some going high as 100 million (Erwin, 1988). Estimates conducted by the authors indicate that projections above 30 million have probabilities of <0.00001. Their estimated range is more likely to be between 2.5 et 3.7 million species (avec 90% confidence). This seems somewhat reasonable given that these extraordinary estimates were based heavily on extrapolation. There are clearly many difficulties in assessing diversity based on tropical arthropod surveys – this paper again uses phytophagous (plant-eating) beetles for estimates. They are careful to point out that these methods do not account for non-phytophagous insects, but assume that they will follow traditional biogeographic patterns of diversity. This is somewhat of a new concept given that when I was in college I was taught that parasitoids are counterintuitively not more diverse in tropical regions. This hypothesis is more often than not being proven false in the light of more precise modern taxonomic methodology. Rather proudly I helped play a role with the parasitoid project at the UIUC. En résumé, host specificity is more extreme in tropical environments with hundreds of cryptic species hidden amongst rapidly radiating groups such as the microgastrine Braconids (Hyménoptères) – the same has held true across similar taxa.

One interesting note about the paper is their inclusion of a secondary estimation based on Lepidoptera canopy assemblages. They assumed that a) all Lepidoptera can be found in the canopy and b) that all leps are phytophagous. This is clearly a very conservative estimation given that not all Lepidoptera are found in the canopy and not all are phytophagous. While I do not have the numbers on hand, a certain percentage of lep diversity must have been excluded from these estimates. I will also go out on a limb and assume that the authors (Novotny 2002) did not include microlepidoptera morphospecies – and most likely estimated abundances with our current taxonomic understanding. However I do not have access to this 2002 paper, so I may be incorrect. Using these Lepidoptera numbers (from the same survey as the Coleoptera) a global diversity was estimated by Hamilton et. al. at around 8.5 millions arthropod species.

While I agree that extraordinary estimates of tens of tens (or hundreds) of millions of arthropod species are probably ridiculous; I am of the camp that current research is indicating that estimates of the lower tens of millions of species are possible. The authors have failed to include research that counterbalances their premise that tropical species exhibit a lower beta diversity (Novotny 2002, 2007). In the same journal, Nature 2007, Dyar et. al. have indicated that the American tropics exhibit a higher beta diversity than previously assumed. Either it can be said that estimates of beta diversity in the australasian tropics are incorrect, or they are incompatible with species assemblages of neotropical forests. All of this speaks to the difficulty in extrapolating estimations of species across all tropical regions. These estimates are based on comprehensive insect surveys of New Guinea, perhaps they do not accurately reflect the true diversity of American tropical forests, and these number ranges are low.

As a final thought, most assesments are focused on tropical arthropods. It seems all too possible that the total number of all species, including bacteria and archaea, can easily exceed tens of millions. But extrapolating those numbers is even more precarious than arthropods, given the extreme lack of knowledge we have.

Par Chris Grinter, on June 4th, 2010

Can’t find a way to link the direct video (not even VodPod), but here is the link to the Daily Show site. How many physicists pulled their hair out when they heard this one? Yikes, he is the newly appointed spokesman. Don’t worry Neil, you’re not going anywhere after this.

Having not aired yet I can’t tell exactly how apologetic the show est, but it seems heavily focused on finding the “creator”. I can hear it in John Stewart’s voice when he pulls back from ripping into Freeman’s “god of the gaps” theory. Perhaps there was an edit and we missed the question where John Stewart asked “Morgan, can you define a logical fallacy for us… perhaps the god of the gaps one?” I believe that any physicist who ever says “god was responsible” says it with no deeper meaning than when Einstein famously evoked god’s dice. That’s to say, a non-literal and non-personal god found only in the beauty and splendor of nature.

Par Chris Grinter, on June 2nd, 2010

S'il y a une chose que j'ai apprise à l'université, c'était comment me distraire facilement. J'ai tendance à laisser ma télé allumée en arrière-plan pendant que je travaille sur mon ordinateur, surtout tard le soir quand je mène habituellement une guerre gagnante contre le sommeil. L'autre nuit, quelque chose a attiré mon attention: un homme tenant des tiges de radiesthésie dans sa cour arrière. Monter le son, laisse couler les conneries. Ce n'était qu'un éclair d'idiotie dans un programme par ailleurs bon sur l'amélioration de l'habitat. Je me suis habitué à la télévision merdique sur des réseaux tels que History Channel ou un réseau Discovery (la qualité de leurs spectacles comprend des joyaux comme “Les hantés: fantômes et animaux de compagnie”), mais j'ai été un peu surpris de voir BS honorer ma station PBS locale.

Plus sur le “Menuiserie américaine” l'hôte Scott Phillips construisait une belle tonnelle de jardin. Vous pouvez regarder le tout ici gratuitement: Épisode 1609: Moulures et garnitures architecturales d'époque. Il n'y a pas d'horodatage sur le clip, mais la radiesthésie arrive vers le milieu. Tout en démontrant les matériaux nécessaires pour fixer le bois au sol, il a mis en garde contre le fait de creuser au hasard dans votre cour sans savoir où se trouve l'eau souterraine., les conduites électriques ou de gaz étaient: des conseils solides. Donc, pour ce faire, vous devez (paraphrasé) “prendre des morceaux de cintre, n'importe quoi fera l'affaire, les transformer en un “L”. Alors que j'avance, les barreaux se croisent – là (ils traversent) – juste là est la ligne d'irrigation. 9 hors de 10 les gens ont cette capacité, mais vous devriez faire appel à un professionnel en cas de doute“. Ma traduction “Ok les gars, ne vous inquiétez pas d'appeler un gars pour faire ça, figure it out this way”. Please tell me what man who seriously watches a home improvement show at midnight would cede authority to someone else before giving it the good ol’ college try? Even if we grant for a moment that 9 hors de 10 people could do this, what about that one guy who can’t? Isn’t it irresponsible to suggest that you can avoid power/water/sewer/gas only 90% of the time? Oups, hit that pesky gas line…

Being a scientist, a skeptic and a procrastinator – I wrote Scott a message about this so I could avoid my work at hand. Today he kindly replied saying: (excerpt)

“Our bodies are electromagnetic fields. Disrupt a field and things happen…. I learned the technique mentioned from a city worker that they used to find lines. Not from a charlatan. My team witnessed the objective use of this technique.”

Briefly, no, our bodies are not electromagnets. Everyone can hold a compass, or TV… without screwing them up. Franz Mesmer coined the idea of “Animal Magnetism” in the last half of the 18th century (also invented “mesmerization” AKA hypnotism) – and had it abruptly debunked by Benjamin Franklin and others. I’m also a bit worried to hear that city workers are relying on dowsing to locate public lines! But to move onward, let us dig into the myths of dowsing. I agree that there seems to be somewhat of an intuitive truth when it comes to dowsing, however false it is scientifically, it remains compelling. Bien sûr… electrical things underground effect sensitive wires above. And wow, look at all these guys who can find water, or power, ou… lost people… ou bombs? D'accord, let’s stick to water for this conversation.

(continued)

Continue reading An Uphill Battle

Par Chris Grinter, le 1er Juin, 2010 Quelques images de leps communs de Californie, prise le long de la côte près de Santa Cruz il y a quelques semaines. Je commence à me frayer un chemin à travers un arriéré de photos…

Euphydryas chalcedona

Plébéjus acmon

Plébéjus acmon

Ethmia arctostaphylella sur Eriodictyon sp.

Une remarque intéressante sur Ethmia arctostaphylella – le nom est un abus de langage, il ne se nourrit pas réellement Arctostaphylos (Manzanita). Au moment de la description dans 1880 Walsingham avait trouvé des larves en train de pupifier sur des feuilles de manzinata et avait supposé que c'était leur plante hôte. Dans la superbe monographie de Jerry Powell sur le groupe, il indique que ce papillon a été élevé à partir de Eriodictyon – qui se trouve être la fleur sur laquelle le papillon est perché. Les deux plantes poussent côte à côte, et il est assez facile de voir comment une chenille errante trouve son chemin vers un voisin.

|

Scepticisme

|