By Chris Grinter, on July 1st, 2010 And now for the even more infrequently reoccurring series, vox populi! For those without scarring high school memories of latin class (through no fault of my teacher) I’ll bring you up to speed – the title roughly translates to “voice of the people”. Here is another old e-mail that I’ve been saving. It is a 100% real message, but of course I have redacted the real names and addresses to protect the innocent. Enjoy! I also highly encourage submissions of your own-

Vetur 2008:

“Hi, I’m so glad I found you. Now, I hope you can help me. 1982, while camping at an old gold mining camp in the Mendocino National Forest I was bitten by a large brown spider. It took three days for the venom to pass through my system. On day three I was 95% blind, the bite swelled to a large grotesquely deep red bump on my arm. I’ll never forget the 12 hours the venom attacked me. The price I payed to survive this spiders venom was…….to loose absolutely all my body fat. I spoke with a doctor from Santa Rosa by phone from a friends place in (some small CA town). He knew about this spider and couldn’t believe I suvived the venom when I told him I lost all my body fat. He also told me it was impossible for someone to survive loosing all their body fat in 12 klukkustundir. I reminded him that this was an impossible situation. He told me that this spider is being kept from the public. I believe this spider came from China or Russia. These spiders don’t share anything with other Cali spiders. They have big bodies and short stout legs. The female that bit me was about 4 inch’s and, had 5 males. Four years later, while living in the Hayward hills, I couldn’t believe my eyes, running across the floor, another one. This spider was about 6 inch’s. I know these spiders don’t climb walls or spin webs. They build nest’s, and obtain 4-5 males to protect her and find food. The female never leave’s the nest except…………when a larger female drives her out and, kills her males. This is when people are bitten by this spider, as she runs around looking for another nest. Bites are very uncommon. I wondered………….how big was the female that drove that 6 inch from her nest. og………….how big do they get. Can I find this spider on display at (your museum)? Is it possible to find all the information their is on this very dangerous spider?”

Continue reading Vox Populi, bindi II

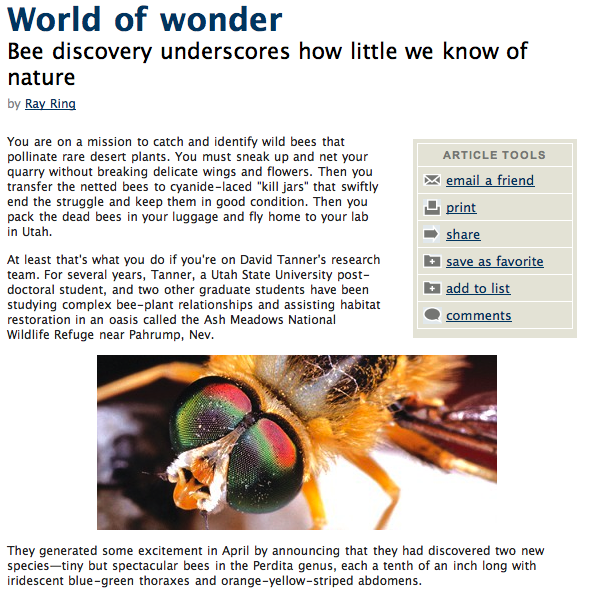

By Chris Grinter, þann 26. júní, 2010 Velkomin í átta bindi af þáttaröðinni sem endurtekur sig ósamræmi, Genius fjölmiðla. Ég rakst á Þessi grein nýlega varðandi landlægt fiðrildi frá Puerto Rico. Hver getur sagt mér nákvæmlega hvers vegna þessi skýrsla er villandi? Það gæti verið aðeins erfiðara en venjulegt GOP (Ég legg til að farga öllum áður tengdum skammstöfunum með þessum stöfum). Vísbending, bara að segja mér að fiðrildið á myndinni sé frá Malasíu er ekki svarið sem ég er að leita að!

By Chris Grinter, on June 23rd, 2010

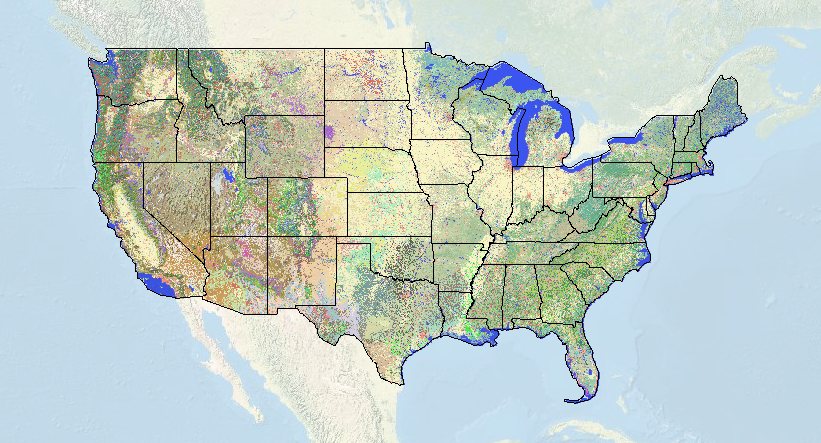

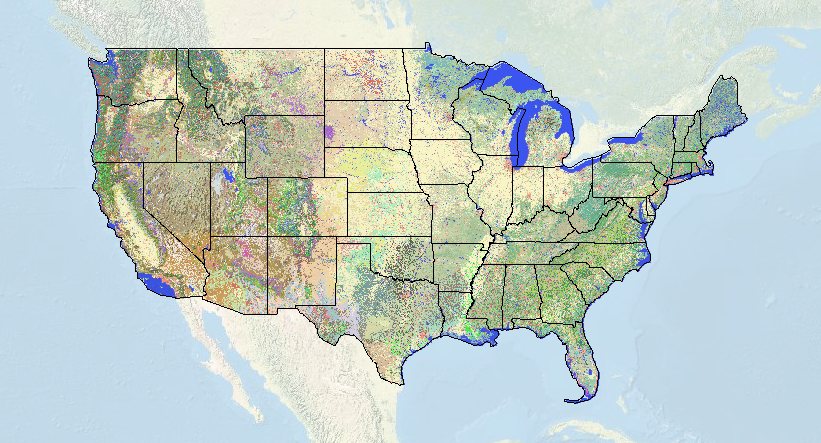

I’ve always wondered how to find the correct terminology for land cover in a given area. Usually, I just ballpark something along the lines of “oak chaparral”. But now I can use this awesome new map brought to us by the USGS/National Biological Information Infrastructure. The level of detail is amazing, and you can specify the degree of accuracy with a drop down tab (1-3). Now with a high-def US topo map I can see exactly where the largest stands of monterrey pine are (actually it’s a California Coastal Closed-Cone Conifer Forest and Woodland) so I can optimally place my trap this weekend.

Continue reading Landscape Cover Map

By Chris Grinter, on June 18th, 2010

Welcome to The Moth and Me #12, and my first blog carnival. Despite blogging for a few months I have yet to take a look back and reflect on exactly how I became enamored with lepidoptera in the first place. Remembering a time or location where this happened is impossible, and like many of my colleagues and I’m sure many of my readers, I had a butterfly net and “bug cage” in hand as soon as I could walk. When it comes to entomology I believe almost everyone falls in love at first with a large and striking insect. For me it was a butterfly, naturally. I can remember staring for endless hours at the diversity of Ornithoptera and Papilio illustrated in Paul Smart’s famous book. Somewhere along the way in pursuit of something new I began to stray into the nocturnal world. Moths comprise the majority of the diversity of Lepidoptera; while there are nearly 11,000 species in the United States, only a few hundred are butterflies. This quickly opened a door (maybe into an abyss…) to the shocking abundance found everywhere around us. This amazing diversity has now drawn me deep into the biology and evolutionary history of the Lepidoptera. Editing these fourteen contributions of moth blogging together I just can’t help but to reflect back on some of my own mothing journey.

Perhaps if I was a child in Europe this moth (Deilephila elpenor porcellus) would have been the first to catch my eye. Over at Urban Moths Ron Laughton has discovered the stunning diversity in his own back yard in much the same way as I did growing up here in the US. Take a look at the types of traps he has been using, most of which he constructed himself. One of the best behaviors of moths is their willingness to dive headlong into the light. Not too far from Ron, Mike Beale has been blogging british moths as well. It can be pretty amazing just how similar our two faunas are (a few moths actually are the same).

Continue reading The Moth and Me #12

By Chris Grinter, þann 11. júní, 2010

This moth is just about as rare as its paranormal namesake (except that it’s real) – it’s a Gazoryctra sp. in the family Hepialidae. They represent a basal lineage of the Lepidoptera and are commonly known as ghost moths or swift moths. Ghost – because males of some species are known to fly in true leks, where they hover up and down in grassy clearings at dusk while females observe. These same males also call for females with pheromones, a bit of a backward situation with insects. Swift- rather self evident, but boreal species have been known to be powerful flyers.

One of the features that help indicate this as a basal lineage is the placement of the wings on the body, some wing venation, reduced or absent mouthparts and the lack of a strong wing coupling device. These moths have a “jugum”, which is a small thumb like projection from the top of the hindwing. Other lineages of moths have a tight coupling mechanism known as the frenulum and retinaculum, where bristles hook the two wings together so they remain coupled during flight. When at rest the jugum folds around and probably helps keep the wings together – but not while in flight; the forewing is out of sync with the hindwing and flight is not dynamic (Scoble 1992).

In the Americas Hepialid biology is very poorly understood. Only a handful of life histories are described globally – all of which seem to be endophagous (boring) in plant root systems. Some early instar larvae may feed in the leaf litter or underground on the root system before entering the rhizome. Australia is fortunate to have a diverse and impressive fauna of Hepialidae – many are brilliantly colored and enormous (250mm or up to 12 tommur!), and a bit better studied. Some larvae are even common enough that aboriginal tribes have used them as a staple food source.

But back to this moth in particular. I collected it in my black light trap last August up in the Sierra Nevada around 10,500 feet. The species is unknown, and may likely be new. The most frustrating part is that it is the only specimen known to science. The entire genus is very rare, except for one or two commoner species, only a few dozen specimens exist. So is it a female of a species described only from a male? A freakish aberration of an otherwise known species? Or maybe it is actually new. I’ve barcoded the DNA, that actually tells me nothing since there are zero sequences from any closely related species. Raunverulega, as far as I know, the other species in the Sierra haven’t even been collected in decades so I can’t even get a sequence from an older specimen. The icing on the cake is their behavior. They rarely, ef nokkurn, come to light – which may be a result of their crepuscular flight. On the right night they may be on the wing for 20-30 minutes, usually a female searching out a male, or a female flying to oviposit (likely just broadcast scatter their eggs on the ground). So come this late August I’ll be returning to the high Sierra with a few volunteers from the entomology department in hopes of seeing one whiz by me on the steep slopes. If I get some more, it might turn out to be impressive new species for California.

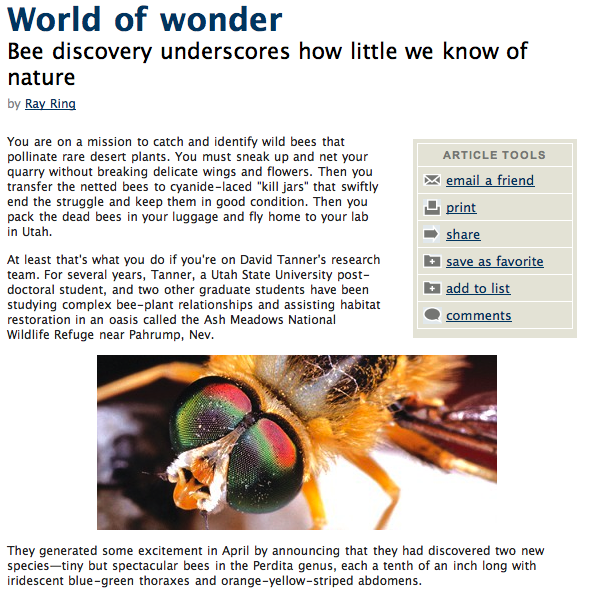

By Chris Grinter, þann 11. júní, 2010 Who can see what’s wrong with Þessi grein?

By Chris Grinter, on June 9th, 2010

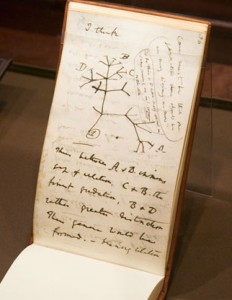

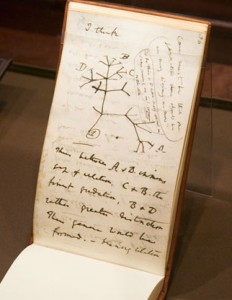

Þetta recent article in the American Naturalist has taken a second look at some of the famously inflated species estimates, some going high as 100 million (Erwin, 1988). Estimates conducted by the authors indicate that projections above 30 million have probabilities of <0.00001. Their estimated range is more likely to be between 2.5 og 3.7 million species (with 90% confidence). This seems somewhat reasonable given that these extraordinary estimates were based heavily on extrapolation. There are clearly many difficulties in assessing diversity based on tropical arthropod surveys – this paper again uses phytophagous (plant-eating) beetles for estimates. They are careful to point out that these methods do not account for non-phytophagous insects, but assume that they will follow traditional biogeographic patterns of diversity. This is somewhat of a new concept given that when I was in college I was taught that parasitoids are counterintuitively not more diverse in tropical regions. This hypothesis is more often than not being proven false in the light of more precise modern taxonomic methodology. Rather proudly I helped play a role with the parasitoid project at the UIUC. Í stuttu máli, host specificity is more extreme in tropical environments with hundreds of cryptic species hidden amongst rapidly radiating groups such as the microgastrine Braconids (Æðavængjum) – the same has held true across similar taxa.

One interesting note about the paper is their inclusion of a secondary estimation based on Lepidoptera canopy assemblages. They assumed that a) all Lepidoptera can be found in the canopy and b) that all leps are phytophagous. This is clearly a very conservative estimation given that not all Lepidoptera are found in the canopy and not all are phytophagous. While I do not have the numbers on hand, a certain percentage of lep diversity must have been excluded from these estimates. I will also go out on a limb and assume that the authors (Novotny 2002) did not include microlepidoptera morphospecies – and most likely estimated abundances with our current taxonomic understanding. However I do not have access to this 2002 paper, so I may be incorrect. Using these Lepidoptera numbers (from the same survey as the Coleoptera) a global diversity was estimated by Hamilton et. al. at around 8.5 millions arthropod species.

While I agree that extraordinary estimates of tens of tens (or hundreds) of millions of arthropod species are probably ridiculous; I am of the camp that current research is indicating that estimates of the lower tens of millions of species are possible. The authors have failed to include research that counterbalances their premise that tropical species exhibit a lower beta diversity (Novotny 2002, 2007). In the same journal, Nature 2007, Dyar et. al. have indicated that the American tropics exhibit a higher beta diversity than previously assumed. Either it can be said that estimates of beta diversity in the australasian tropics are incorrect, or they are incompatible with species assemblages of neotropical forests. All of this speaks to the difficulty in extrapolating estimations of species across all tropical regions. These estimates are based on comprehensive insect surveys of New Guinea, perhaps they do not accurately reflect the true diversity of American tropical forests, and these number ranges are low.

As a final thought, most assesments are focused on tropical arthropods. It seems all too possible that the total number of all species, including bacteria and archaea, can easily exceed tens of millions. But extrapolating those numbers is even more precarious than arthropods, given the extreme lack of knowledge we have.

By Chris Grinter, on June 4th, 2010

Can’t find a way to link the direct video (not even VodPod), but here is the link to the Daily Show site. How many physicists pulled their hair out when they heard this one? Yikes, he is the newly appointed spokesman. Don’t worry Neil, you’re not going anywhere after this.

Having not aired yet I can’t tell exactly how apologetic the show er, but it seems heavily focused on finding the “creator”. I can hear it in John Stewart’s voice when he pulls back from ripping into Freeman’s “god of the gaps” theory. Perhaps there was an edit and we missed the question where John Stewart asked “Morgan, can you define a logical fallacy for us… perhaps the god of the gaps one?” I believe that any physicist who ever says “god was responsible” says it with no deeper meaning than when Einstein famously evoked god’s dice. That’s to say, a non-literal and non-personal god found only in the beauty and splendor of nature.

By Chris Grinter, 2. júní, 2010

Ef það er eitt sem ég lærði í háskóla, það var hvernig til auðveldlega afvegaleiða mig. ÉG hafa tilhneigingu til að halda sjónvarpið mitt á í bakgrunni á meðan ég er að vinna á tölvunni minni, sérstaklega seint á kvöldin þegar ég er yfirleitt að berjast aðlaðandi stríð gegn svefni. The other night something did catch my eye: a man holding dowsing rods in his back yard. Volume up, let the bullshit flow. It was just a flash of idiocy in an otherwise good program on home improvement. I’ve become accustom to crap-based TV on networks such as the History Channel or a Discovery network (quality of their shows include gems like “The Haunted: ghosts and pets”), but I was a little surprised to see BS grace my local PBS station.

Over on the “American Woodshop” host Scott Phillips was constructing a beautiful garden arbor. You can watch the entire thing here for free: Episode 1609: Period Architectural Moldings and Trim. There are no time stamps on the clip, but the dowsing comes in around the mid-point. While demonstrating the materials needed to secure the wood to the ground he cautioned against digging haphazardly into your yard without knowing where the underground water, electrical or gas lines were: solid advice. So in order to do this you should (umorðað) “take pieces of coat-hanger, anything will do, turn them into an “The”. As I walk forward the bars cross – það (they cross) – right there is the irrigation line. 9 out of 10 people have this ability, but you should call in a professional if there is any doubt“. My translation “OK guys, don’t worry about calling in some guy to do this, figure it out this way”. Please tell me what man who seriously watches a home improvement show at midnight would cede authority to someone else before giving it the good ol’ college try? Even if we grant for a moment that 9 out of 10 people could do this, what about that one guy who can’t? Isn’t it irresponsible to suggest that you can avoid power/water/sewer/gas only 90% þess tíma? Oops, hit that pesky gas line…

Being a scientist, a skeptic and a procrastinator – I wrote Scott a message about this so I could avoid my work at hand. Today he kindly replied saying: (excerpt)

“Our bodies are electromagnetic fields. Disrupt a field and things happen…. I learned the technique mentioned from a city worker that they used to find lines. Not from a charlatan. My team witnessed the objective use of this technique.”

Briefly, ekki, our bodies are not electromagnets. Everyone can hold a compass, or TV… without screwing them up. Franz Mesmer coined the idea of “Animal Magnetism” in the last half of the 18th century (also invented “mesmerization” AKA hypnotism) – and had it abruptly debunked by Benjamin Franklin and others. I’m also a bit worried to hear that city workers are relying on dowsing to locate public lines! But to move onward, let us dig into the myths of dowsing. I agree that there seems to be somewhat of an intuitive truth when it comes to dowsing, however false it is scientifically, it remains compelling. viss… electrical things underground effect sensitive wires above. Og vá, sjáðu alla þessa gaura sem geta fundið vatn, eða kraftur, eða… glatað fólk… eða bombs? OK, let’s stick to water for this conversation.

(continued)

Continue reading An Uphill Battle

By Chris Grinter, þann 1. júní, 2010 Just a few images of common California leps, taken along the coast range near Santa Cruz a few weeks ago. Starting to work my way through some photo backlog…

Euphydryas chalcedona

plebeian ACMO

plebeian ACMO

Ethmia arctostaphylella á Eriodictyon sp.

One interesting note on Ethmia arctostaphylella – the name is a misnomer, it does not actually feed on Arctostaphylos (Manzanita). At the time of description in 1880 Walsingham had found larvae pupating on leaves of manzinata and assumed it was their host plant. In Jerry Powell’s stunning monograph of the group he indicates this moth was reared from Eriodictyon – which happens to be the flower the moth is perched on. The two plants grow side by side, and it’s pretty easy to see how a wandering caterpillar finds its way onto a neighbor.

|

Efahyggja

|