By Chris Grinter, on July 25th, 2011 This Monday I am departing from the usual Arctiinae for something completely different – a microlep! This is a Nepticulidae, Stigmella diffasciae, and it measures in at a whopping 6 mm. I can’t take credit for spreading this moth – all of the nepticulids I have photographed are from the California Academy of Sciences and spread by Dave Wagner while he was here for a postdoctorate position.

The caterpillars mine the upper-side of the leaves of Ceanothus and are known only from the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California. If you’re so inclined the revision of the North American species of the genus is freely available here (.pdf).

Stigmella diffasciae (Nepticulidae)

By Chris Grinter, on July 22nd, 2011 It’s been a little while since the last GOP challenge, but this is a softball. I’m hoping they were just too lazy to find a more suitable image…

By Chris Grinter, on July 19th, 2011 What would Jesus do if he had some free time – maybe cure a disease, end a war, or feed the starving – but nah, everyone sees that coming. Why not shock them to the core – burn your face on a Walmart receipt! At least, that’s what a couple in South Carolina believe to have found, a Walmart receipt with Jesus’s face on it. This isn’t exactly new or exciting, humans have a wonderful ability to recognize a face in just about anything. Jesus and other characters “appear” on random things all the time, and even in 2005 a shrine was built to the Virgin Mary around a water stain in a Chicago underpass.

Pareidolia anyone? Actually, that face looks pretty convincing, I’m not too sure this wasn’t just faked or “enhanced”. The closeups even look like there are fingerprints all over it. Since I don’t have a walmart anywhere near me or a walmart receipt on hand I can’t determine how sensitive the paper is and how easy it would have been to do – but how long do you think before it shows up on ebay? In any event, it looks much more like James Randi to me than Jesus (at least we actually know what Randi looks like!).

from CNN

By Chris Grinter, on July 18th, 2011 Over on Arthropoda, fellow SFS blogger Michael Bok shared an image of his field buddy, Plugg the green tree frog. My first thought was of a similar tree frog that haunted welcomed me everywhere I went in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. Needless to say, Costa Rica instills a sudden habit of double checking everything you are about to do. This species is known as the milk frog (Phrynohyas venulosa) for their copious amounts of milky white toxic secretions. One of the first stories Dan Janzen told me while while I was with him at Santa Rosa was about this species – and accidentally rubbing his eye after holding it. Thankfully the blindness and burning was only temporary.

Milk Frog: Phrynohyas venulosa

By Chris Grinter, on July 18th, 2011 I’ll keep the ball rolling with Arctiinae and post a photo today of Ctenucha brunnea. This moth can be common in tall grasses along beaches from San Francisco to LA – although in recent decades the numbers of this moth have been declining with habitat destruction and the invasion of beach grass (Ammophila arenaria). But anywhere there are stands of giant ryegrass (Leymus condensatus) you should find dozens of these moths flying in the heat of the day or nectaring on toyon.

Ctenucha brunnea (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

By Chris Grinter, on July 12th, 2011 Well as you may have guessed the subject isn’t as shocking as my title suggests, but I couldn’t help but to spin from the Guardian article. I really find it hilarious when I come across anything that says scientists are “astounded”, “baffled”, “shocked”, “puzzled”, – I guess that’s a topic for another time… Nevertheless a really cool butterfly has emerged at the “Sensational Butterflies” exhibit at the British Museum in London – a bilateral gynandromorph! The Guardian reports today that this specimen of Papilio memnon just emerged and is beginning to draw small crowds of visitors. I know I’d love to see one of these alive again – although the zoo situation would take away quite a bit of the excitement. I think the only thing more exciting than seeing one of these live in the field would be to net one myself!

One little thing tripped my skeptical sensors and that is the quote at the end of the article taken from the curator of butterflies, Blanca Huertas. “The gynandromorph butterfly is a fascinating scientific phenomenon, and is the product of complex evolutionary processes. It is fantastic to have discovered one hatching on museum grounds, particularly as they are so rare.”

Well, I don’t specifically see how these are a “product of … evolutionary processes” inasmuch as all life in all forms is a product of evolution. These are sterile “glitches” that are cool, but not anything that has been specifically evolved for or against. Perhaps it would be more adept to call this a fascinating process of genetics (which the article actually describes with accuracy). Also – butterflies emerge as adults and hatch as caterpillars – but that’s just me being picky.

By Chris Grinter, on July 11th, 2011 Today’s moth is a beautiful and rare species from SE Arizona and Mexico: Lerina incarnata (Erebidae: Arctiinae). Like many other day flying species it is brilliantly colored and quite likely aposematic. After all, the host plant is a milkweed and the caterpillar is just as stunning (below).

Lerina incarnata (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

This image of an old, spread specimen hardly does the animal justice, but one lucky photographer found a female ovipositing at the very top of a hill outside of Tucson, Arizona. While you’re at it go check out some of Philip’s other great photographs on SmugMug.

Lerina incarnata - Philip Kline, BugGuide As I mentioned above this moth also has an equally impressive caterpillar that feeds on Ascleapias linaria (pineneedle milkweed).

By Chris Grinter, on July 5th, 2011

It seems like there is a preponderance of urban legends that involve insects crawling into our faces while we sleep. The most famous myth is something along the lines of “you eat 8 spiders a year while sleeping“. Actually when you google that the number ranges from 4 to 8… up to a pound? Not surprising things get so exaggerated online, especially when it concerns the ever so popular arachnophobia. I doubt the average American eats more than a few spiders over their entire lifetime; your home simply shouldn’t be crawling with so many spiders that they end up in your mouth every night! A similar myth is still a myth but with a grain of truth – that earwigs burrow into your brain at night to lay eggs. It isn’t true that earwigs are human parasites (thankfully), but they do have a predisposition to crawl into tight, damp places. It is possible that this was a frequent enough occurrence in Ye Olde England that the earwig earned this notorious name. Cockroaches have also been documented as ear-spelunkers – but any crawly insect that might be walking on us at night could conceivably end up in one of our orifices.

I have however never heard of a moth crawling into an ear until I came across this story today! I guess a confused Noctuid somehow ended up in this boy’s ear, although I can’t help but to wonder if he put it there himself… Moths aren’t usually landing on people while they are asleep nor are they that prone to find damp, tight spots. But then again anything is possible, some noctuids do crawl under bark or leaves in the daytime for safe hiding. I even came across another story of an ear-moth form the UK (not that the Daily Mail is a reputable source).

Naturally, some lazy news sources are using file photos of “moths” instead of copying the photo from the original story. It’s extra hilarious because one of the pictures used is of a new species of moth described last year by Bruce Walsh in Arizona. Lithophane leeae has been featured on my blog twice before, but never like this!

On a closing note here is a poem by Robert Cording (also where the above image was found).

Consider this: a moth flies into a man’s ear

One ordinary evening of unnoticed pleasures.

When the moth beats its wings, all the winds

Of earth gather in his ear, roar like nothing

He has ever heard. He shakes and shakes

His head, has his wife dig deep into his ear

With a Q-tip, but the roar will not cease.

It seems as if all the doors and windows

Of his house have blown away at once—

The strange play of circumstances over which

He never had control, but which he could ignore

Until the evening disappeared as if he had

Never lived it. His body no longer

Seems his own; he screams in pain to drown

Out the wind inside his ear, and curses God,

Who, hours ago, was a benign generalization

In a world going along well enough.

On the way to the hospital, his wife stops

The car, tells her husband to get out,

To sit in the grass. There are no car lights,

No streetlights, no moon. She takes

A flashlight from the glove compartment

And holds it beside his ear and, unbelievably,

The moth flies towards the light. His eyes

Are wet. He feels as if he’s suddenly a pilgrim

On the shore of an unexpected world.

When he lies back in the grass, he is a boy

Again. His wife is shining the flashlight

Into the sky and there is only the silence

He has never heard, and the small road

Of light going somewhere he has never been.

– Robert Cording, Common Life: Poems (Fort Lee: CavanKerry Press, 2006), 29–30.

By Chris Grinter, on June 30th, 2011

Micronecta scholtzi The hills of the European countryside are alive in the chorus of amorous, screaming, male aquatic bugs. The little insect above, Micronecta scholtzi (Corixidae), measures in at a whopping 2.3mm and yet produces a clicking/buzzing sound easily audible to the human ear above the water surface. To put that in perspective: trying to hear someone talk underwater while standing poolside is nearly impossible, yet this minute insect generates a click loud enough to be mistaken for a terrestrial arthropod. While that doesn’t sound too impressive when we are surrounded by other loud insects like the cicada, M. scholtzi turns out to be a stunningly loud animal when you take into consideration the body size and medium the sound is propagating through to reach our ear. Put into numbers the intensity of the clicks underwater can reach up to 100 dB (Sound Pressure Level, SPL). Shrink us into the insect world and this sound production is equal to a jackhammer at the same distance! So what on earth has allowed this little bug to make this noise and get away with it in a world full of predators?

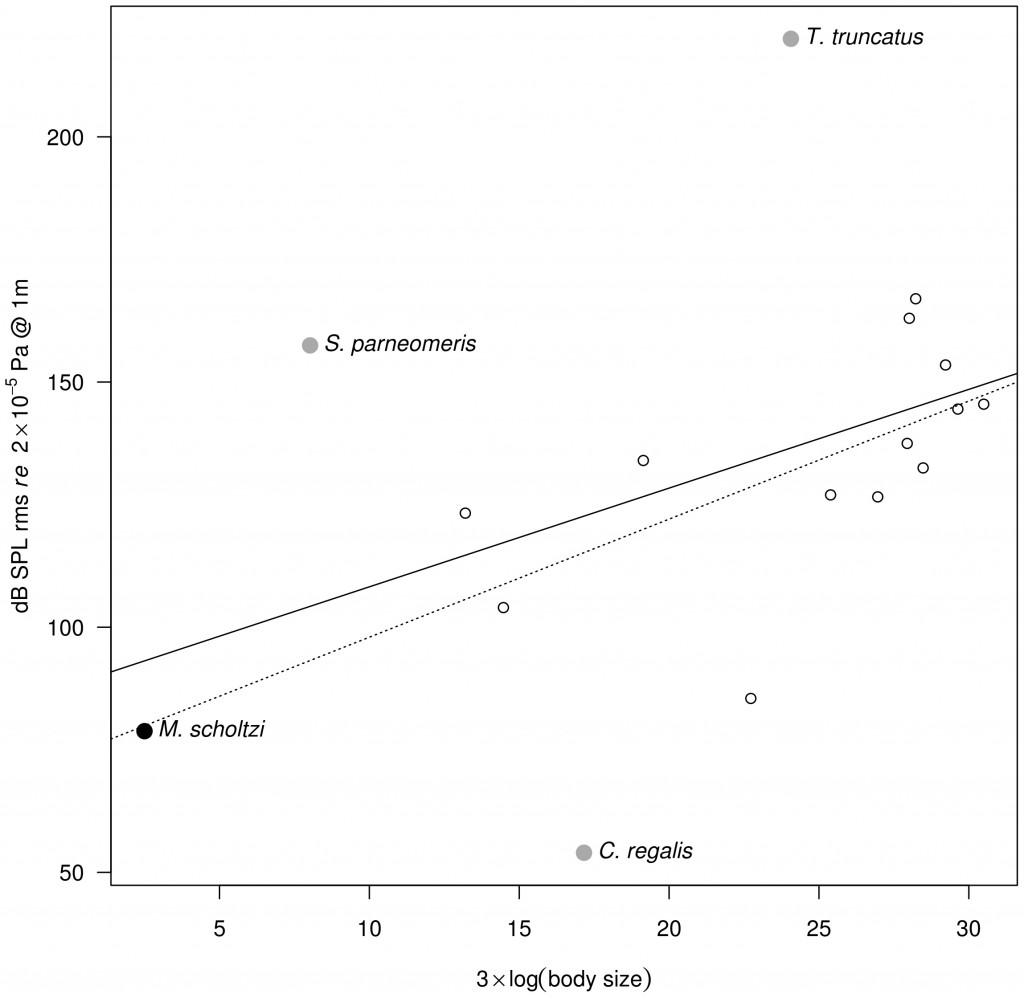

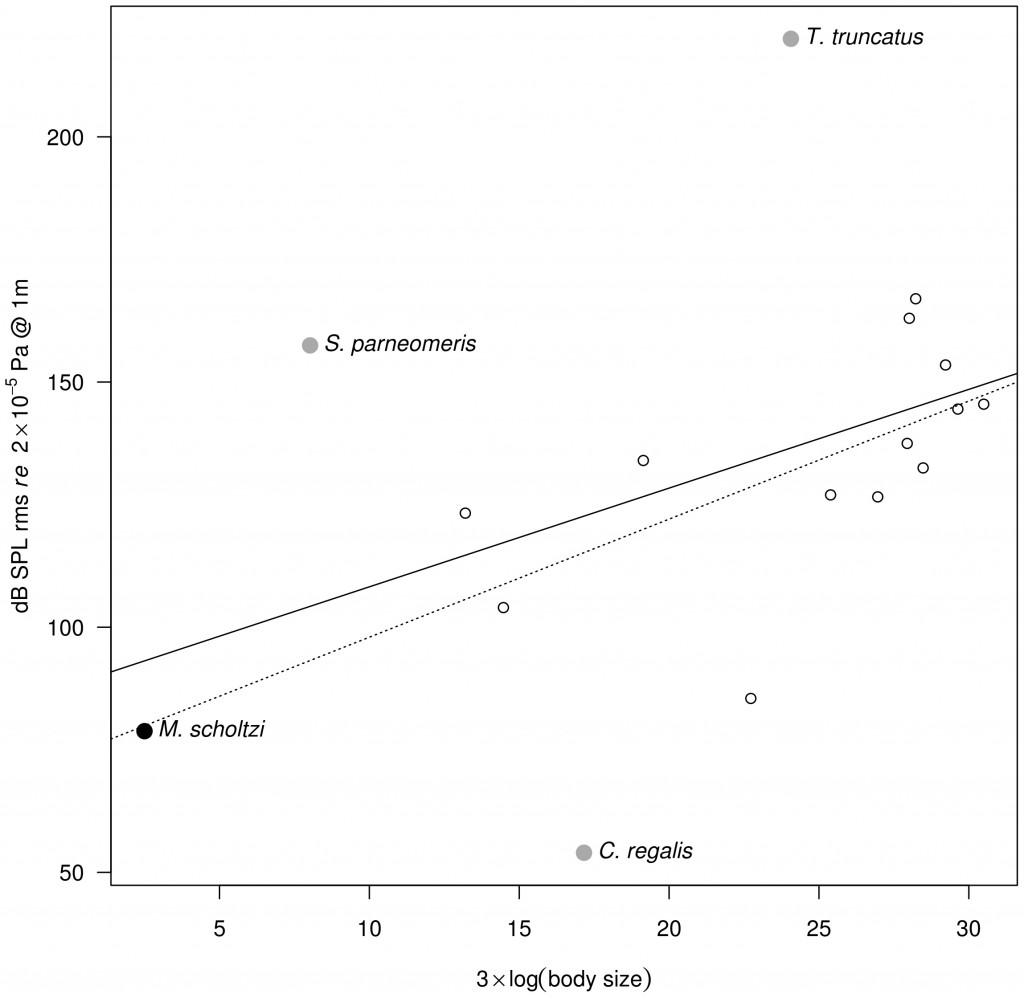

The authors naturally point out how surprising these results are. The first thing that becomes apparent is that the water boatmen must have no auditory predators since they are basically swimming around making the most noise physically possible for any small animal anywhere. Really this isn’t too surprising since most underwater predators are strictly visual hunters (dragonfly larvae, water bugs and beetles etc…). It is very likely that sexual selection has guided the development of these stridulatory calls into such astounding levels. The second most surprising thing is clear once you graph just how loud these insects are relative to their body size. At the top of the graph is the bottlenose dolphin (T. truncatus) with its famous sonar. But the greatest outlier is actually our little insect in the bottom left with the very highest ratio between sound and body size (31.5 with a mean of 6.9). No other known animal comes close. It is likely though that further examination of other aquatic insects may yield similar if not more surprising results!

To be more accurate about the “screaming”, the bugs (bugs in this instance is correct; the Corixidae belong to the order Hemiptera – the true bugs) are likely to be stridulating – rubbing together two parts to generate sound instead of exhaling air, drumming, etc… In the article the authors speculate that the “sound is produced by rubbing a pars stridens on the right paramere (genitalia appendage) against a ridge on the left lobe of the eighth abdominal segment [15]”. Without pulling up their citation, it appears that stridulation by males in the genus is well documented for mate attraction. And as you would expect, news outlets and science journalists read “genitalia appendage” and translate that to penis: and you end up with stories like this. The function of the parameres can be loosely translated to similar to mandibles in that they are opposing structures (usually armed with hairs) for grasping. The exact use of them may differ by species or even orders, but they are very distinct form the penis (=aedeagus) since they simply help facilitate mating and don’t deliver any sperm. So in reality you have genital “claspers” with a “pars stridens”. And the best illustration of a pars stridens is over on the old blog Archetype. This structure is highlighted below in yellow (and happens to exist on the abdomen of the ant). But in short – it’s a regular grooved surface akin to a washboard. In the end the sentence quoted above should be translated to “two structures at the tip of the abdomen that rub together like two fingers snapping”.

Detail of the pars stridens (in yellow) on the forth abdominal tergite in a Pachycondyla villosa worker (Scanning Electron Micrograph, Roberto Keller/AMNH) Continue reading The incredibly loud world of bug sex

By Chris Grinter, on June 20th, 2011 I’m going to keep the ball rolling with this series and try to make it more regular. I will also focus on highlighting a new species each week from the massive collections here at the California Academy of Sciences. This should give me enough material for… at least a few hundred years.

Grammia edwardsii (Erebidae: Arctiinae) This week’s specimen is the tiger moth Grammia edwardsii. Up until a few years ago this family of moths was considered separate from the Noctuidae – but recent molecular and morphological analysis shows that it is in fact a Noctuid. The family Erebidae was pulled out from within the Noctuidae and the Arctiidae were placed therein, turning them into the subfamily Arctiinae. OK boring taxonomy out of the way – all in all, it’s a beautiful moth and almost nothing is known about it. This specimen was collected in San Francisco in 1904 – in fact almost all specimens known of this species were collected in the city around the turn of the century. While this moth looks very similar to the abundant and widespread Grammia ornata, close analysis of the eyes, wing shape and antennae maintain that this is actually a separate species. I believe the last specimen was collected around the 1920’s and it hasn’t been seen since. It is likely and unfortunate that this moth may have become extinct over the course of the last 100 years of development of the SF Bay region. Grammia, and Arctiinae in general, are not known for high levels of host specificity; they tend to be like little cows and feed on almost anything in their path. So it remains puzzling why this moth wouldn’t have habitat today, even in a city so heavily disturbed. Perhaps this moth specialized in the salt marsh areas surrounding the bay – which have all since been wiped out due to landfill for real-estate (1/3 of the entire bay was lost to fill). Or perhaps this moth remains with us even today but is never collected because it is an evasive day flying species. I always keep my eye out in the park in spring for a small orange blur…

|

Skepticism

|