Por Chris Grinter, on July 25th, 2011 This Monday I am departing from the usual Arctiinae for something completely different – a microlep! This is a Nepticulidae, Stigmella diffasciae, and it measures in at a whopping 6 mm. I can’t take credit for spreading this moth – all of the nepticulids I have photographed are from the California Academy of Sciences and spread by Dave Wagner while he was here for a postdoctorate position.

The caterpillars mine the upper-side of the leaves of Ceanothus and are known only from the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California. If you’re so inclined the revision of the North American species of the genus is freely available here (.pdf).

Stigmella diffasciae (Nepticulidae)

Por Chris Grinter, el 22 de julio, 2011 Ha sido un poco de tiempo desde el último desafío del Partido Republicano, pero esta es una pelota de softball. Espero que eran demasiado perezosos para encontrar una imagen más adecuada…

Por Chris Grinter, el 19 de julio, 2011 ¿Qué haría Jesús si tuviera algo de tiempo libre? – tal vez curar una enfermedad, terminar una guerra, o alimentar a los hambrientos – pero no, todos ven eso venir. ¿Por qué no sorprenderlos hasta la médula? – quemarse la cara en un recibo de Walmart! Al menos, that’s what a couple in South Carolina believe to have found, un Walmart receipt with Jesus’s face on it. This isn’t exactly new or exciting, humans have a wonderful ability to recognize a face in just about anything. Jesus and other characters “appear” on random things all the time, and even in 2005 a shrine was built to the Virgin Mary around a water stain in a Chicago underpass.

Pareidolia anyone? En realidad, that face looks pretty convincing, I’m not too sure this wasn’t just faked or “enhanced”. The closeups even look like there are fingerprints all over it. Since I don’t have a walmart anywhere near me or a walmart receipt on hand I can’t determine how sensitive the paper is and how easy it would have been to do – but how long do you think before it shows up on ebay? En cualquier evento, it looks much more like James Randi to me than Jesus (at least we actually know what Randi looks like!).

from CNN

Por Chris Grinter, el 18 de julio, 2011 Más en Arthropoda, compañero SFS blogger Michael Bok compartió una imagen de su amigo campo, Plugg la rana de árbol verde. My first thought was of a similar tree frog that haunted welcomed me everywhere I went in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. No hace falta decir, Costa Rica instills a sudden habit of double checking everything you are about to do. This species is known as the milk frog (Phrynohyas venulosa) for their copious amounts of milky white toxic secretions. One of the first stories Dan Janzen told me while while I was with him at Santa Rosa was about this species – and accidentally rubbing his eye after holding it. Thankfully the blindness and burning was only temporary.

Milk Frog: Phrynohyas venulosa

Por Chris Grinter, el 18 de julio, 2011 I’ll keep the ball rolling with Arctiinae and post a photo today of Ctenucha brunnea. This moth can be common in tall grasses along beaches from San Francisco to LA – although in recent decades the numbers of this moth have been declining with habitat destruction and the invasion of beach grass (Ammophila arenaria). But anywhere there are stands of giant ryegrass (Leymus condensatus) you should find dozens of these moths flying in the heat of the day or nectaring on toyon.

Ctenucha brunnea (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

Por Chris Grinter, on July 12th, 2011 Well as you may have guessed the subject isn’t as shocking as my title suggests, but I couldn’t help but to spin from the Guardian article. I really find it hilarious when I come across anything that says scientists are “astounded”, “baffled”, “shocked”, “puzzled”, – I guess that’s a topic for another time… Nevertheless a realmente cool butterfly has emerged at the “Sensational Butterflies” exhibit at the British Museum in London – a bilateral gynandromorph! The Guardian reports today that this specimen of Papilio memnon just emerged and is beginning to draw small crowds of visitors. I know I’d love to see one of these alive again – although the zoo situation would take away quite a bit of the excitement. I think the only thing more exciting than seeing one of these live in the field would be to net one myself!

One little thing tripped my skeptical sensors and that is the quote at the end of the article taken from the curator of butterflies, Blanca Huertas. “The gynandromorph butterfly is a fascinating scientific phenomenon, and is the product of complex evolutionary processes. It is fantastic to have discovered one hatching on museum grounds, particularly as they are so rare.”

Bien, I don’t specifically see how these are a “product of … evolutionary processes” inasmuch as todo life in todo forms is a product of evolution. These are sterile “glitches” that are cool, but not anything that has been specifically evolved for or against. Perhaps it would be more adept to call this a fascinating process of genetics (which the article actually describes with accuracy). también – butterflies emerge as adults and hatch as caterpillars – but that’s just me being picky.

Por Chris Grinter, el 11 de julio, 2011 La polilla de hoy es una especie hermosa y rara del sureste de Arizona y México: Lerina encarnada (Erebidae: Arctiinae). Como muchas otras especies voladoras diurnas, tiene colores brillantes y es muy probable que sea aposemática.. Después de todo, la planta huésped es un algodoncillo y la oruga es igual de impresionante (abajo).

Lerina encarnada (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

Esta imagen de un viejo, espécimen esparcido apenas hace justicia al animal, pero un fotógrafo afortunado encontró una hembra ovipositando en la cima de una colina en las afueras de Tucson, Arizona. Mientras lo haces, echa un vistazo a algunas de las otras excelentes fotografías de Philip. en SmugMug.

Lerina encarnada - felipe kline, Guía de errores Como mencioné anteriormente, esta polilla también tiene una oruga igualmente impresionante que se alimenta de Ascleapias linaria (algodoncillo).

Por Chris Grinter, el 5 de julio, 2011

Parece que hay una preponderancia de leyendas urbanas que involucran insectos que se meten en la cara mientras dormimos.. El mito más famoso es algo parecido a “comes 8 arañas al año mientras duermes“. En realidad, cuando buscas en Google, el número oscila entre 4 a 8… hasta una libra? No es de extrañar que las cosas se exageren tanto en Internet, especialmente cuando se trata de la siempre tan popular aracnofobia. Dudo que el estadounidense promedio coma más que unas pocas arañas durante toda su vida.; tu casa simplemente no debería estar plagada de tantas arañas que terminen en tu boca todas las noches! Un mito similar sigue siendo un mito pero con una pizca de verdad. – que las tijeretas se esconden en tu cerebro por la noche para poner huevos. No es cierto que las tijeretas sean parásitos humanos (agradecidamente), pero tienen predisposición a meterse en situaciones difíciles., lugares húmedos. Es posible que esto fuera algo bastante frecuente en Ye Olde Inglaterra que la tijereta se ganó este notorio nombre. Las cucarachas también han sido documentadas como espeleólogos. – pero cualquier insecto reptante que pudiera estar caminando sobre nosotros por la noche podría terminar en uno de nuestros orificios..

Sin embargo, nunca había oído hablar de una polilla metiéndose en una oreja hasta que encontré esta historia hoy! Supongo que un Noctuid confundido de alguna manera terminó en el oído de este chico., aunque no puedo evitar preguntarme si él mismo lo puso allí… Las polillas no suelen posarse sobre las personas mientras duermen ni son tan propensas a encontrar humedad., puntos estrechos. Pero claro, todo es posible., Algunos noctuidos se arrastran bajo la corteza o las hojas durante el día para esconderse de forma segura.. Incluso me encontré otra historia de una polilla del oído del Reino Unido (No es que el Daily Mail sea una fuente confiable.).

Naturalmente, Algunas fuentes de noticias perezosas son usando fotos de archivo de “polillas” en lugar de copiar la foto de la historia original. Es muy gracioso porque una de las imágenes utilizadas es la de una nueva especie de polilla descrita. el año pasado por Bruce Walsh en arizona. Lithophane leeae ha aparecido en mi blog dos veces antes, pero nunca así!

Como nota final, aquí hay un poema de Robert Cording. (también donde la imagen de arriba fue encontrado).

Considera esto: una polilla vuela al oído de un hombre

Una velada cualquiera de placeres inadvertidos.

Cuando la polilla bate sus alas, todos los vientos

De la tierra se juntan en su oído, rugir como si nada

Él alguna vez ha escuchado. Él tiembla y tiembla

Su cabeza, hace que su esposa le clave profundamente en la oreja

Con un hisopo, pero el rugido no cesará.

Parece como si todas las puertas y ventanas

De su casa han volado de inmediato.

El extraño juego de circunstancias sobre el cual

nunca tuvo el control, pero que podría ignorar

Hasta que la tarde desapareció como si hubiera

nunca lo viví. Su cuerpo ya no

Parece suyo; grita de dolor para ahogarse

Fuera el viento dentro de su oído, y maldice a Dios,

OMS, horas atras, fue una generalización benigna

En un mundo que va bastante bien.

De camino al hospital, su esposa se detiene

El coche, le dice a su marido que se vaya,

Sentarse en la hierba. No hay luces en el auto,

Sin alumbrado público, no LUNA. Ella toma

Una linterna de la guantera.

Y lo sostiene al lado de su oreja y, increíblemente,

La polilla vuela hacia la luz.. Sus ojos

estan mojados. Se siente como si de repente fuera un peregrino.

En la orilla de un mundo inesperado.

Cuando se recuesta en la hierba, él es un muchacho

De nuevo. Su esposa está alumbrando la linterna.

Hacia el cielo y solo existe el silencio.

el nunca ha escuchado, y el pequeño camino

De la luz yendo a algún lugar donde nunca ha estado.

– Robert Cording, Vida común: Poemas (fuerte lee: Prensa Cavan Kerry, 2006), 29–30.

Por Chris Grinter, on June 30th, 2011

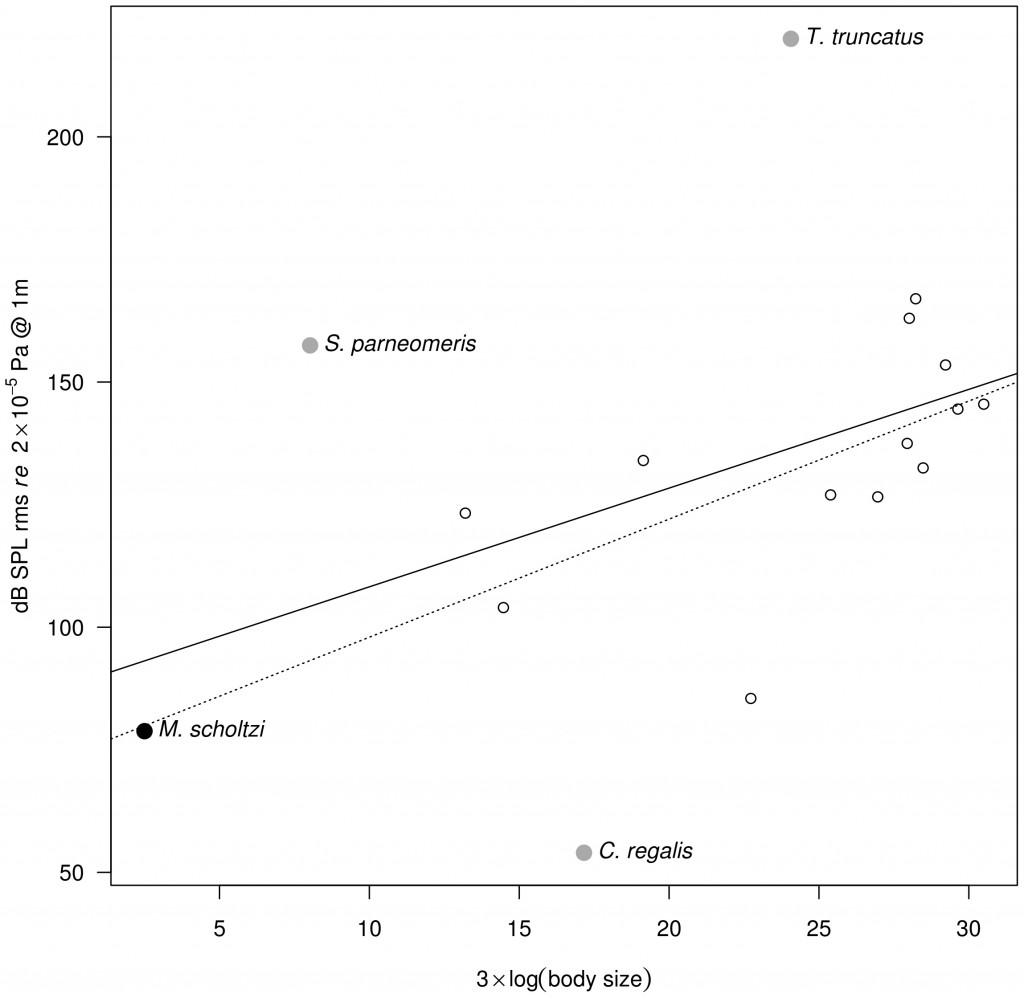

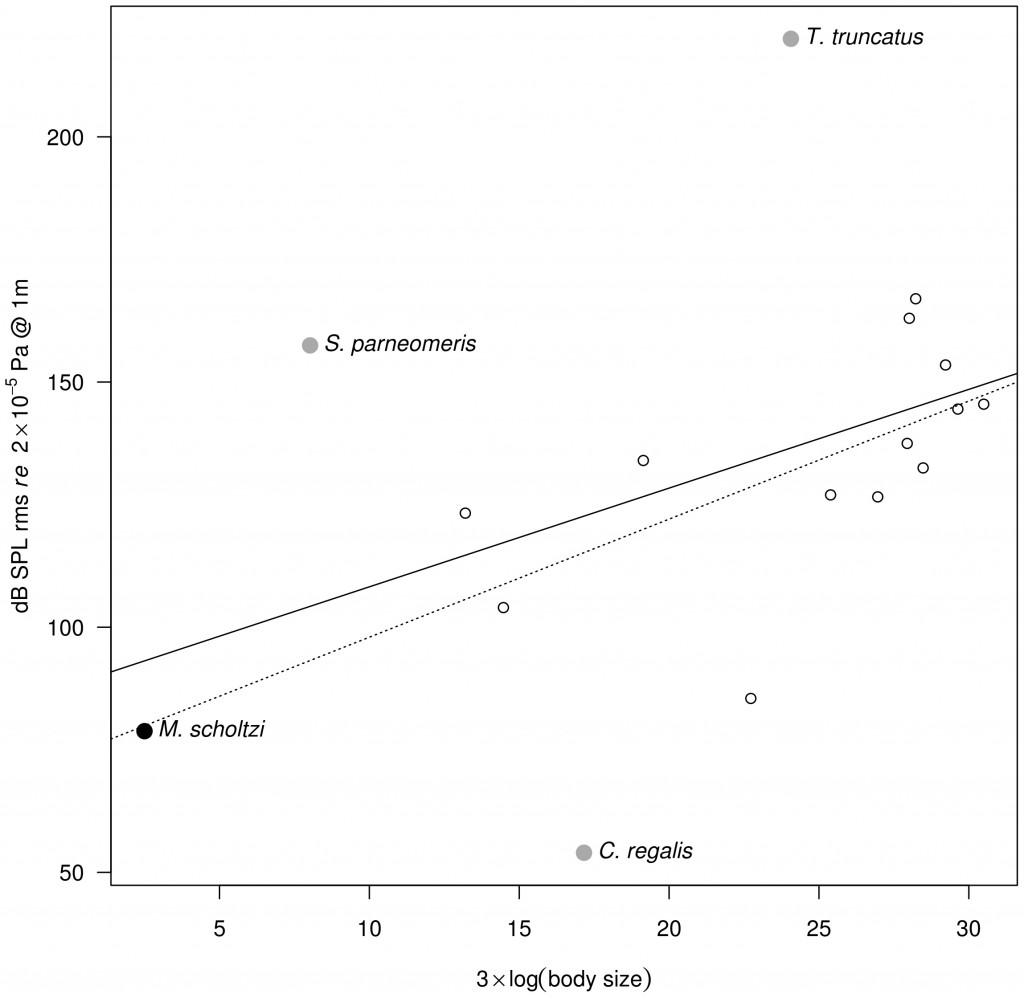

Micronecta scholtzi The hills of the European countryside are alive in the chorus of amorous, screaming, male aquatic bugs. The little insect above, Micronecta scholtzi (Corixidae), measures in at a whopping 2.3mm and yet produces a clicking/buzzing sound easily audible to the human ear above the water surface. To put that in perspective: trying to hear someone talk underwater while standing poolside is nearly impossible, yet this minute insect generates a click loud enough to be mistaken for a terrestrial arthropod. While that doesn’t sound too impressive when we are surrounded by other loud insects like the cicada, METRO. scholtzi turns out to be a stunningly loud animal when you take into consideration the body size and medium the sound is propagating through to reach our ear. Put into numbers the intensity of the clicks underwater can reach up to 100 dB (Sound Pressure Level, SPL). Shrink us into the insect world and this sound production is equal to a jackhammer at the same distance! So what on earth has allowed this little bug to make this noise and get away with it in a world full of predators?

The authors naturally point out how surprising these results are. The first thing that becomes apparent is that the water boatmen must have no auditory predators since they are basically swimming around making the most noise physically possible for any small animal anywhere. Really this isn’t too surprising since most underwater predators are strictly visual hunters (dragonfly larvae, water bugs and beetles etc…). It is very likely that sexual selection has guided the development of these stridulatory calls into such astounding levels. The second most surprising thing is clear once you graph just how loud these insects are relative to their body size. At the top of the graph is the bottlenose dolphin (T. truncatus) with its famous sonar. But the greatest outlier is actually our little insect in the bottom left with the very highest ratio between sound and body size (31.5 with a mean of 6.9). No other known animal comes close. It is likely though that further examination of other aquatic insects may yield similar if not more surprising results!

To be more accurate about the “screaming”, the bugs (bugs in this instance is correct; the Corixidae belong to the order Hemiptera – the true bugs) are likely to be stridulating – rubbing together two parts to generate sound instead of exhaling air, drumming, etc.… In the article the authors speculate that the “sound is produced by rubbing a pars stridens on the right paramere (genitalia appendage) against a ridge on the left lobe of the eighth abdominal segment [15]”. Without pulling up their citation, it appears that stridulation by males in the genus is well documented for mate attraction. And as you would expect, news outlets and science journalists read “genitalia appendage” and translate that to penis: and you end up with stories like this. The function of the parameres can be loosely translated to similar to mandibles in that they are opposing structures (usually armed with hairs) for grasping. La exact use of them may differ by species or even orders, but they are very distinct form the penis (=aedeagus) since they simply help facilitate mating and don’t deliver any sperm. So in reality you have genital “claspers” con un “pars stridens”. And the best illustration of a pars stridens is over on the old blog Archetype. This structure is highlighted below in yellow (and happens to exist on the abdomen of the ant). But in short – it’s a regular grooved surface akin to a washboard. In the end the sentence quoted above should be translated to “two structures at the tip of the abdomen that rub together like two fingers snapping”.

Detail of the pars stridens (in yellow) on the forth abdominal tergite in a Pachycondyla villosa worker (Scanning Electron Micrograph, Roberto Keller/AMNH) Continue reading The incredibly loud world of bug sex

Por Chris Grinter, on June 20th, 2011 I’m going to keep the ball rolling with this series and try to make it more regular. I will also focus on highlighting a new species each week from the massive collections here at the California Academy of Sciences. This should give me enough material for… at least a few hundred years.

Grammia edwardsii (Erebidae: Arctiinae) This week’s specimen is the tiger moth Grammia edwardsii. Up until a few years ago this family of moths was considered separate from the Noctuidae – but recent molecular and morphological analysis shows that it is in fact a Noctuid. The family Erebidae was pulled out from within the Noctuidae and the Arctiidae were placed therein, turning them into the subfamily Arctiinae. OK boring taxonomy out of the way – all in all, it’s a beautiful moth and almost nothing is known about it. This specimen was collected in San Francisco in 1904 – in fact almost all specimens known of this species were collected in the city around the turn of the century. While this moth looks very similar to the abundant and widespread Grammia ornata, close analysis of the eyes, wing shape and antennae maintain that this is actually a separate species. I believe the last specimen was collected around the 1920’s and it hasn’t been seen since. It is likely and unfortunate that this moth may have become extinct over the course of the last 100 years of development of the SF Bay region. Grammia, and Arctiinae in general, are not known for high levels of host specificity; they tend to be like little cows and feed on almost anything in their path. So it remains puzzling why this moth wouldn’t have habitat today, even in a city so heavily disturbed. Perhaps this moth specialized in the salt marsh areas surrounding the bay – which have all since been wiped out due to landfill for real-estate (1/3 of the entire bay was lost to fill). Or perhaps this moth remains with us even today but is never collected because it is an evasive day flying species. I always keep my eye out in the park in spring for a small orange blur…

|

Escepticismo

|