Chris Grinter, on July 25th, 2011 This Monday I am departing from the usual Arctiinae for something completely different – a microlep! This is a Nepticulidae, Stigmella diffasciae, and it measures in at a whopping 6 mm. I can’t take credit for spreading this moth – all of the nepticulids I have photographed are from the California Academy of Sciences and spread by Dave Wagner while he was here for a postdoctorate position.

The caterpillars mine the upper-side of the leaves of Ceanothus and are known only from the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California. If you’re so inclined the revision of the North American species of the genus is freely available here (.PDF).

Stigmella diffasciae (Nepticulidae)

Chris Grinter, 22. heinäkuuta, 2011 Edellisestä GOP-haastuksesta on vähän aikaa, mutta this is a softball. Toivon, että he olivat liian laiskoja löytääkseen sopivamman kuvan…

Chris Grinter, on July 19th, 2011 What would Jesus do if he had some free time – maybe cure a disease, end a war, or feed the starving – but nah, everyone sees that coming. Why not shock them to the core – burn your face on a Walmart receipt! Vähintään, that’s what a couple in South Carolina believe to have found, a Walmart receipt with Jesus’s face on it. This isn’t exactly new or exciting, humans have a wonderful ability to recognize a face in just about anything. Jesus and other characters “appear” on random things all the time, and even in 2005 a shrine was built to the Virgin Mary around a water stain in a Chicago underpass.

Pareidolia anyone? Todella, that face looks pretty convincing, I’m not too sure this wasn’t just faked or “enhanced”. The closeups even look like there are fingerprints all over it. Since I don’t have a walmart anywhere near me or a walmart receipt on hand I can’t determine how sensitive the paper is and how easy it would have been to do – but how long do you think before it shows up on ebay? Joka tapauksessa, it looks much more like James Randi to me than Jesus (at least we actually know what Randi looks like!).

from CNN

Chris Grinter, 18. heinäkuuta, 2011 Yli koskevat Arthropoda, kaveri SFS bloggaaja Michael Bok jakoi kuvan hänen kentän kaveri, Plugg vihreä puu sammakko. My first thought was of a similar tree frog that haunted welcomed me everywhere I went in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. Tarpeetonta sanoa, Costa Rica instills a sudden habit of double checking everything you are about to do. This species is known as the milk frog (Phrynohyas venulosa) for their copious amounts of milky white toxic secretions. One of the first stories Dan Janzen told me while while I was with him at Santa Rosa was about this species – and accidentally rubbing his eye after holding it. Thankfully the blindness and burning was only temporary.

Milk Frog: Phrynohyas venulosa

Chris Grinter, 18. heinäkuuta, 2011 I’ll keep the ball rolling with Arctiinae and post a photo today of Ctenucha brunnea. Tämä koi voi olla yleisempää pitkä heinät pitkin rantoja San Franciscosta LA – vaikka viime vuosikymmeninä numerot tämän koi on vähenemässä elinympäristöjen tuhoutuminen ja hyökkäys rannalla ruoho (Rantakaura). But anywhere there are stands of giant ryegrass (Leymus condensatus) you should find dozens of these moths flying in the heat of the day or nectaring on toyon.

Ctenucha brunnea (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

Chris Grinter, heinäkuun 12. päivänä, 2011 Kuten ehkä arvasit, aihe ei ole niin järkyttävä kuin otsikoni antaa ymmärtää, mutta en voinut muuta kuin poimia Guardianin artikkelista. Minusta on todella hilpeä, kun törmään mihinkään, mikä väittää, että tiedemiehet ovat “hämmästynyt”, “hämmentynyt”, “järkyttynyt”, “ymmällään”, – Taitaa olla toisen kerran aihe… Siitä huolimatta a todella cool butterfly has emerged at the “Sensational Butterflies” exhibit at the British Museum in London – a bilateral gynandromorph! The Guardian reports today that this specimen of Papilio memnon just emerged and is beginning to draw small crowds of visitors. I know I’d love to see one of these alive again – although the zoo situation would take away quite a bit of the excitement. I think the only thing more exciting than seeing one of these live in the field would be to net one myself!

One little thing tripped my skeptical sensors and that is the quote at the end of the article taken from the curator of butterflies, Blanca Huertas. “The gynandromorph butterfly is a fascinating scientific phenomenon, and is the product of complex evolutionary processes. It is fantastic to have discovered one hatching on museum grounds, particularly as they are so rare.”

Hyvin, I don’t specifically see how these are a “product of … evolutionary processes” inasmuch as kaikki life in kaikki forms is a product of evolution. These are sterile “glitches” that are cool, but not anything that has been specifically evolved for or against. Perhaps it would be more adept to call this a fascinating process of genetics (which the article actually describes with accuracy). Myös – butterflies emerge as adults and hatch as caterpillars – but that’s just me being picky.

Chris Grinter, on July 11th, 2011 Today’s moth is a beautiful and rare species from SE Arizona and Mexico: Lerina incarnata (Erebidae: Arctiinae). Like many other day flying species it is brilliantly colored and quite likely aposematic. After all, the host plant is a milkweed and the caterpillar is just as stunning (alla).

Lerina incarnata (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

This image of an old, spread specimen hardly does the animal justice, but one lucky photographer found a female ovipositing at the very top of a hill outside of Tucson, Arizona. While you’re at it go check out some of Philip’s other great photographs on SmugMug.

Lerina incarnata - Philip Kline, BugGuide As I mentioned above this moth also has an equally impressive caterpillar that feeds on Ascleapias linaria (pineneedle milkweed).

Chris Grinter, 5. heinäkuuta, 2011

Tuntuu siltä on voittopuolisesti kaupunkien legendaa, joissa hyönteiset ryömimisestä kasvomme, kun nukumme. Tunnetuin myytti on jotain tapaan “syöt 8 hämähäkkejä vuosi nukkuessaan“. Oikeastaan kun google että määrä vaihtelee 4 8… kiloon asti? Ei ole yllättävää, että asiat liioittelevat verkossa, varsinkin kun se koskee aina niin suosittua araknofobiaa. Epäilen, että keskiverto amerikkalainen syö enemmän kuin muutama hämähäkki koko elämänsä aikana; kodissasi ei yksinkertaisesti pitäisi olla niin paljon hämähäkkejä, että ne päätyvät suuhusi joka ilta! Samanlainen myytti on edelleen myytti, mutta jossa on totuuden siemen – että korvahuukut kaivautuvat aivoihisi yöllä munimaan. Ei ole totta, että korvasilmukat ovat ihmisen loisia (onneksi), mutta heillä on taipumus ryömiä tiukkaan, kosteat paikat. On mahdollista, että tämä tapahtui riittävän usein vuonna Ye Olde England että korvaperukka ansaitsi tämän pahamaineisen nimen. Torakat on myös dokumentoitu korvien spellunkersiksi – mutta mikä tahansa ryömivä hyönteinen, joka saattaa kävellä päällämme yöllä, saattaa päätyä johonkin aukkoamme.

En ole kuitenkaan koskaan kuullut koikon ryömivän korvaan ennen kuin törmäsin tämä tarina tänään! Luulen, että hämmentynyt Noctuid päätyi jotenkin tämän pojan korvaan, vaikka en voi muuta kuin ihmetellä, laittoiko hän sen itse… Koit eivät yleensä laskeudu ihmisten päälle heidän nukkuessaan, eivätkä ne ole taipuvaisia kosteaan, tiukat kohdat. Mutta sitten taas kaikki on mahdollista, Jotkut yöeläimet ryömivät päiväsaikaan kuoren tai lehtien alle piiloutuakseen turvallisesti. Jopa törmäsin toinen tarina korvakoi Iso-Britanniasta (ei sillä, että Daily Mail olisi hyvämaineinen lähde).

Luonnollisesti, jotkut laiskot uutislähteet ovat käyttämällä tiedostokuvia “koit” sen sijaan, että kopioit valokuvan alkuperäisestä tarinasta. Se on erityisen hauska, koska yksi käytetyistä kuvista on kuvatusta uudesta koilajista viime vuonna Bruce Walsh Arizonassa. Litofaani leeae on ollut esillä blogissani kahdesti aiemmin, mutta ei koskaan näin!

Lopuksi tässä on Robert Cordingin runo (myös missä yllä oleva kuva Havaittiin).

Harkitse tätä: koi lentää miehen korvaan

Yksi tavallinen huomaamattomien nautintojen ilta.

Kun koi lyö siipiään, kaikki tuulet

Kerää maasta hänen korvaansa, ulvoa kuin ei mitään

Hän on koskaan kuullut. Hän tärisee ja tärisee

Hänen päänsä, on vaimonsa kaivaa syvälle hänen korvaansa

Q-kärjellä, mutta karjunta ei lakkaa.

Näyttää siltä, että kaikki ovet ja ikkunat

Hänen talonsa räjähti heti pois -

Olosuhteiden outo leikki, jonka yli

Hänellä ei koskaan ollut kontrollia, mutta jonka hän saattoi jättää huomiotta

Kunnes ilta katosi kuin olisi

Ei koskaan elänyt sitä. Hänen ruumiinsa ei enää

Näyttää omalta; hän huutaa kivusta hukkuakseen

Tuuli hänen korvansa sisällä, ja kiroaa Jumalaa,

WHO, tunteja sitten, oli hyväntahtoinen yleistys

Maailmassa, joka menee tarpeeksi hyvin.

Matkalla sairaalaan, hänen vaimonsa pysähtyy

Auto, käskee miestään poistumaan,

Istumaan nurmikolla. Autossa ei ole valoja,

Ei katuvaloja, ei kuuta. Hän ottaa

Taskulamppu hansikaslokerosta

Ja pitää sitä korvansa vieressä ja, uskomattoman,

Koi lentää kohti valoa. Hänen silmänsä

Ovat märkiä. Hän tuntee olevansa yhtäkkiä pyhiinvaeltaja

Odottamattoman maailman rannalla.

Kun hän makaa nurmikolla, hän on poika

Uudelleen. Hänen vaimonsa valaisee taskulamppua

Taivaalle ja siellä on vain hiljaisuus

Hän ei ole koskaan kuullut, ja pieni tie

Valo menee jonnekin, jossa hän ei ole koskaan ollut.

– Robert Cording, Yhteinen Elämä: Runoja (Fort Lee: CavanKerry Press, 2006), 29–30.

Chris Grinter, on June 30th, 2011

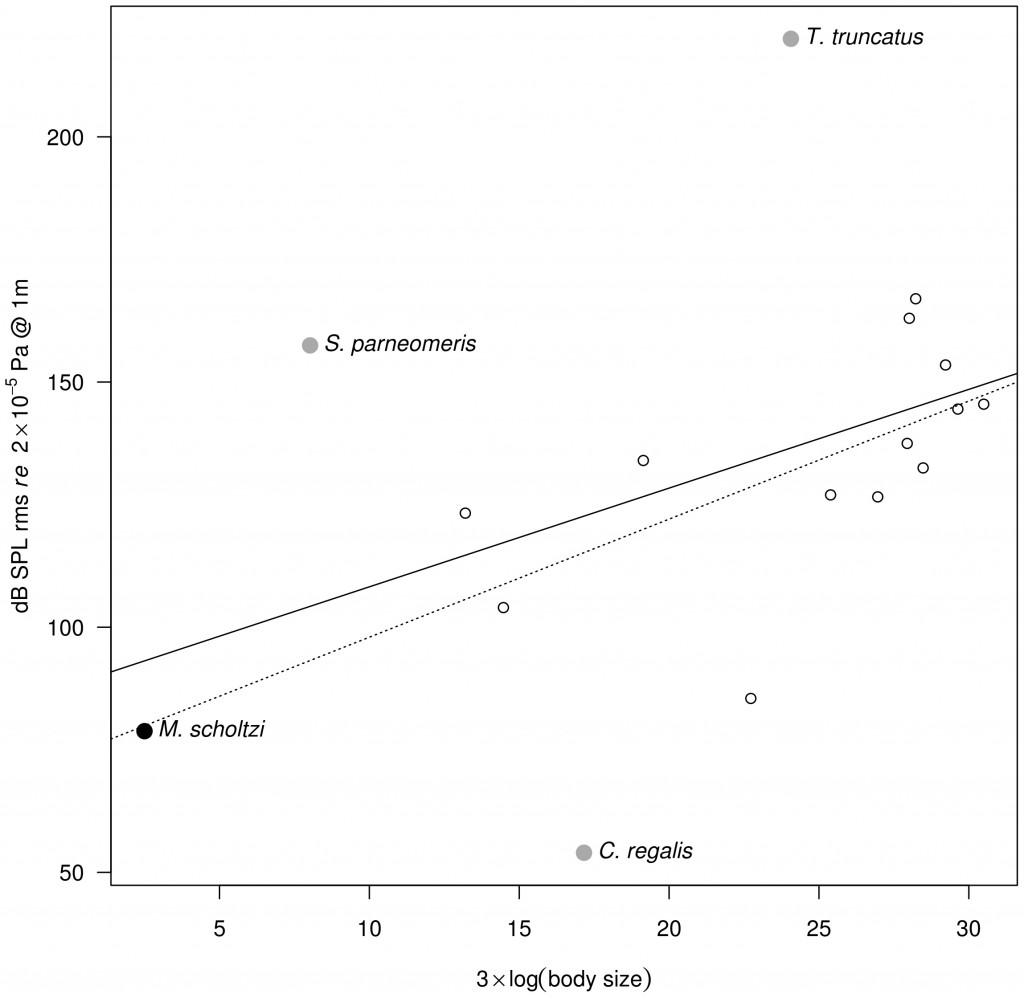

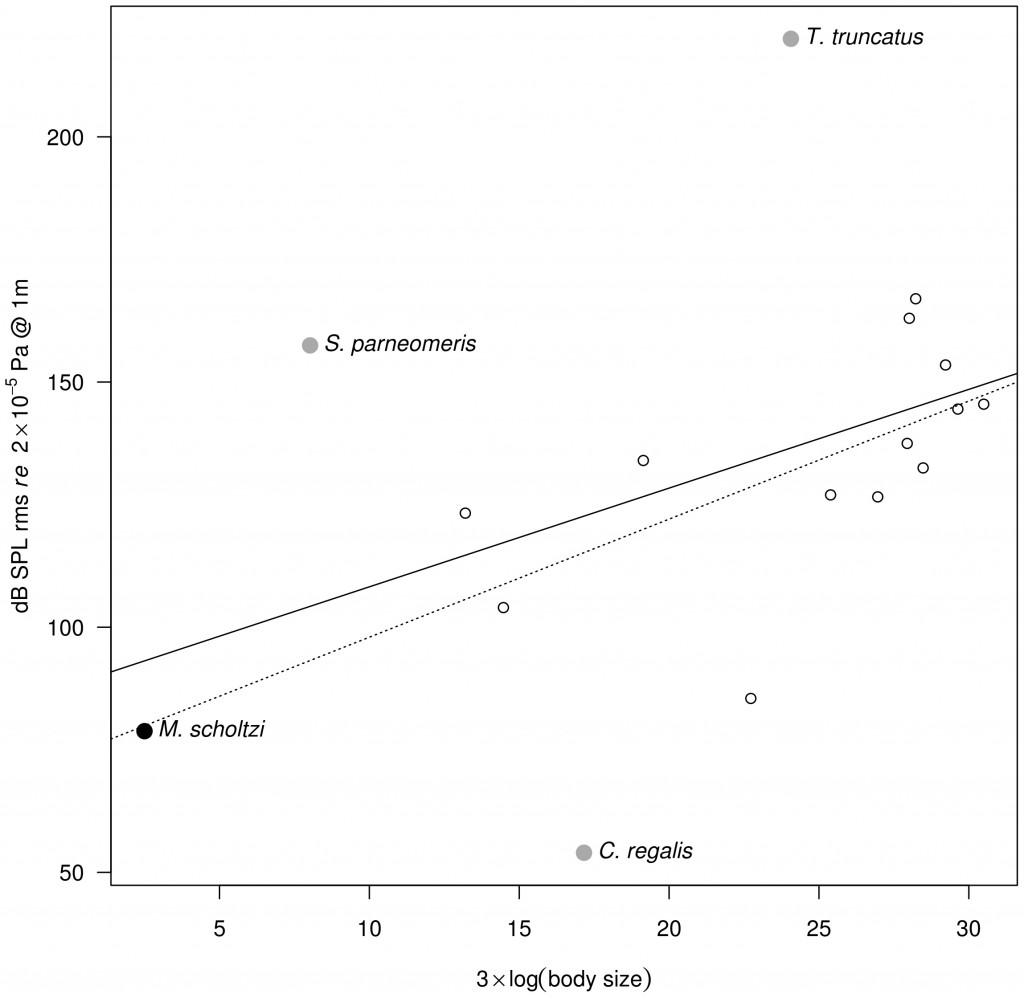

Micronecta scholtzi The hills of the European countryside are alive in the chorus of amorous, screaming, male aquatic bugs. The little insect above, Micronecta scholtzi (Corixidae), measures in at a whopping 2.3mm and yet produces a clicking/buzzing sound easily audible to the human ear above the water surface. To put that in perspective: trying to hear someone talk underwater while standing poolside is nearly impossible, yet this minute insect generates a click loud enough to be mistaken for a terrestrial arthropod. While that doesn’t sound too impressive when we are surrounded by other loud insects like the cicada, M. scholtzi turns out to be a stunningly loud animal when you take into consideration the body size and medium the sound is propagating through to reach our ear. Put into numbers the intensity of the clicks underwater can reach up to 100 dB (Sound Pressure Level, SPL). Shrink us into the insect world and this sound production is equal to a jackhammer at the same distance! So what on earth has allowed this little bug to make this noise and get away with it in a world full of predators?

The authors naturally point out how surprising these results are. The first thing that becomes apparent is that the water boatmen must have no auditory predators since they are basically swimming around making the most noise physically possible for any small animal anywhere. Really this isn’t too surprising since most underwater predators are strictly visual hunters (dragonfly larvae, water bugs and beetles etc…). It is very likely that sexual selection has guided the development of these stridulatory calls into such astounding levels. The second most surprising thing is clear once you graph just how loud these insects are relative to their body size. At the top of the graph is the bottlenose dolphin (T. truncatus) with its famous sonar. But the greatest outlier is actually our little insect in the bottom left with the very highest ratio between sound and body size (31.5 with a mean of 6.9). No other known animal comes close. It is likely though that further examination of other aquatic insects may yield similar if not more surprising results!

To be more accurate about the “screaming”, the bugs (bugs in this instance is correct; the Corixidae belong to the order Hemiptera – the true bugs) are likely to be stridulating – rubbing together two parts to generate sound instead of exhaling air, drumming, jne… In the article the authors speculate that the “sound is produced by rubbing a pars stridens on the right paramere (genitalia appendage) against a ridge on the left lobe of the eighth abdominal segment [15]”. Without pulling up their citation, it appears that stridulation by males in the genus is well documented for mate attraction. And as you would expect, news outlets and science journalists read “genitalia appendage” and translate that to penis: and you end up with stories like this. The function of the parameres can be loosely translated to similar to mandibles in that they are opposing structures (usually armed with hairs) for grasping. The exact use of them may differ by species or even orders, but they are very distinct form the penis (=aedeagus) since they simply help facilitate mating and don’t deliver any sperm. So in reality you have genital “claspers” with a “pars stridens”. And the best illustration of a pars stridens is over on the old blog Archetype. This structure is highlighted below in yellow (and happens to exist on the abdomen of the ant). But in short – it’s a regular grooved surface akin to a washboard. In the end the sentence quoted above should be translated to “two structures at the tip of the abdomen that rub together like two fingers snapping”.

Detail of the pars stridens (in yellow) on the forth abdominal tergite in a Pachycondyla villosa worker (Scanning Electron Micrograph, Roberto Keller/AMNH) Continue reading The incredibly loud world of bug sex

Chris Grinter, 20. kesäkuuta, 2011 Aion pitää lähtölaskennan tämän sarjan ja yrittää tehdä säännöllisemmin. Aion myös keskittyä esiin uusia lajeja viikoittain massiivinen kokoelmista täällä California Academy of Sciences. Tämän pitäisi antaa minulle tarpeeksi materiaalia… ainakin muutama sata vuotta.

Grammia edwardsii (Erebidae: Arctiinae) This week’s specimen is the tiger moth Grammia edwardsii. Up until a few years ago this family of moths was considered separate from the Noctuidae – but recent molecular and morphological analysis shows that it is in fact a Noctuid. The family Erebidae was pulled out from within the Noctuidae and the Arctiidae were placed therein, turning them into the subfamily Arctiinae. OK boring taxonomy out of the way – all in all, it’s a beautiful moth and almost nothing is known about it. This specimen was collected in San Francisco in 1904 – in fact almost all specimens known of this species were collected in the city around the turn of the century. While this moth looks very similar to the abundant and widespread Grammia ornata, close analysis of the eyes, wing shape and antennae maintain that this is actually a separate species. I believe the last specimen was collected around the 1920’s and it hasn’t been seen since. It is likely and unfortunate that this moth may have become extinct over the course of the last 100 years of development of the SF Bay region. Grammia, and Arctiinae in general, are not known for high levels of host specificity; they tend to be like little cows and feed on almost anything in their path. So it remains puzzling why this moth wouldn’t have habitat today, even in a city so heavily disturbed. Perhaps this moth specialized in the salt marsh areas surrounding the bay – which have all since been wiped out due to landfill for real-estate (1/3 of the entire bay was lost to fill). Or perhaps this moth remains with us even today but is never collected because it is an evasive day flying species. I always keep my eye out in the park in spring for a small orange blur…

|

Skeptisyys

|