Chris Grinter, július 25-én, 2011 Ez a hétfő én indul a szokásos Arctiinae valami teljesen más – a microlep! Ez egy Nepticulidae, Stigmella diffasciae, és mér egy óriási 6 mm. Nem viszi el terjed ez moly – összes nepticulids általam fényképezett vannak a California Academy of Sciences és terjed Dave Wagner, amíg ő volt itt egy postdoctorate pozíció.

A hernyók enyém a felső oldalán a levelek Ceanothus és ismert, csak a lábainál a Sierra Nevada Kaliforniában. Ha annyira hajlik a felülvizsgálatát az észak-amerikai faj, a nemzetség szabadon elérhető itt (.pdf).

Stigmella diffasciae (paránypillefélék)

Chris Grinter, július 22-én, 2011 It’s been a little while since the last GOP challenge, de this is a softball. I’m hoping they were just too lazy to find a more suitable image…

Chris Grinter, július 19-én, 2011 Mit tenne Jézus, ha volt egy kis szabad ideje – Talán gyógyítható valamilyen betegség, a végén a háború, vagy takarmány az éhező – de nah, mindenki látja, hogy jön. Miért nem sokk őket, hogy a mag – éget arcod egy Walmart átvételét! Legalább, that’s what a couple in South Carolina believe to have found, egy Walmart receipt with Jesus’s face on it. This isn’t exactly new or exciting, humans have a wonderful ability to recognize a face in just about anything. Jesus and other characters “appear” on random things all the time, and even in 2005 a shrine was built to the Virgin Mary around a water stain in a Chicago underpass.

Pareidolia anyone? Tulajdonképpen, that face looks pretty convincing, I’m not too sure this wasn’t just faked or “enhanced”. The closeups even look like there are fingerprints all over it. Since I don’t have a walmart anywhere near me or a walmart receipt on hand I can’t determine how sensitive the paper is and how easy it would have been to do – but how long do you think before it shows up on ebay? Mindenesetre, it looks much more like James Randi to me than Jesus (at least we actually know what Randi looks like!).

from CNN

Chris Grinter, július 18-án, 2011 Több mint ízeltábúakra, fickó SFS blogger Michael Bok megosztott egy képet az ő területén buddy, Plugg a zöld levelibéka. Az első gondolatom egy hasonló levelibéka volt kísértetjárta üdvözölt mindenhol, ahol jártam a Santa Rosa Nemzeti Parkban, Costa Rica. Mondanom sem kell, Costa Rica hirtelen megszokta, hogy mindent kétszer ellenőriz, amit tenni készül. Ezt a fajt tejbéka néven ismerik (Phrynohyas venulosa) bőséges mennyiségű tejfehér mérgező váladékuk miatt. Az egyik első történet, amit Dan Janzen mesélt nekem, miközben vele voltam Santa Rosában, erről a fajról szólt – és véletlenül megdörzsölte a szemét, miután megfogta. Szerencsére a vakság és égés csak átmeneti volt.

Tejbéka: Phrynohyas venulosa

Chris Grinter, július 18-án, 2011 I’ll keep the ball rolling with Arctiinae and post a photo today of Ctenucha brunnea. This moth can be common in tall grasses along beaches from San Francisco to LA – although in recent decades the numbers of this moth have been declining with habitat destruction and the invasion of beach grass (Ammophila arenaria). But anywhere there are stands of giant ryegrass (Leymus condensatus) you should find dozens of these moths flying in the heat of the day or nectaring on toyon.

Ctenucha brunnea (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

Chris Grinter, július 12-én, 2011 Nos, ahogy sejtheti, a téma nem olyan sokkoló, mint a címem sugallja, de nem tudtam nem pörgetni a Guardian cikkéből. Nagyon mulatságosnak tartom, amikor bármivel találkozom, amiről azt mondják, hogy a tudósok azok “elképedve”, “értetlenül”, “döbbent”, “zavart”, – Azt hiszem, ez egy másik téma… Ennek ellenére a tényleg hűvös pillangó jelent meg a “Szenzációs pillangók” kiállítás a londoni British Museumban – kétoldali gynandromorf! – írja a Guardian ma, hogy ez a példány Papilio memnon most jelent meg, és kezdi vonzani a látogatók kis tömegeit. Tudom, hogy szívesen látnék még egy ilyet élve – bár az állatkerti helyzet eléggé elvenné az izgalmakat. Szerintem az egyetlen izgalmasabb dolog, mint ezek közül egyet látni élni a mezőn az lenne, ha magam neteznék egyet!

Egy apróság megzavarta a szkeptikus szenzoraimat, ez a cikk végén található idézet a pillangók kurátorától, Fehér gyümölcsösök. “A gynandromorph pillangó lenyűgöző tudományos jelenség, és összetett evolúciós folyamatok eredménye. Fantasztikus, hogy felfedeztünk egy kikelőt a múzeum területén, főleg, hogy olyan ritkák.”

Jól, Nem látom konkrétan, hogy ezek a “gyártja … evolúciós folyamatok” annyiban összes élet benne összes formák az evolúció terméke. Ezek sterilek “hibákat” amik menők, de semmi olyat, amit kifejezetten mellette vagy ellene fejlesztettek ki. Talán helyénvalóbb lenne ezt a genetika lenyűgöző folyamatának nevezni (amit a cikk valójában pontosan leír). Is – a lepkék kifejlett korukban kelnek elő és hernyóként kelnek ki – de ez csak én vagyok válogatós.

Chris Grinter, on July 11th, 2011 Today’s moth is a beautiful and rare species from SE Arizona and Mexico: Lerina incarnata (Erebidae: Arctiinae). Like many other day flying species it is brilliantly colored and quite likely aposematic. After all, the host plant is a milkweed and the caterpillar is just as stunning (alatt).

Lerina incarnata (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

This image of an old, spread specimen hardly does the animal justice, but one lucky photographer found a female ovipositing at the very top of a hill outside of Tucson, Arizona. While you’re at it go check out some of Philip’s other great photographs on SmugMug.

Lerina incarnata - Philip Kline, BugGuide As I mentioned above this moth also has an equally impressive caterpillar that feeds on Ascleapias linaria (pineneedle milkweed).

Chris Grinter, on July 5th, 2011

It seems like there is a preponderance of urban legends that involve insects crawling into our faces while we sleep. The most famous myth is something along the lines of “you eat 8 spiders a year while sleeping“. Actually when you google that the number ranges from 4 to 8… up to a pound? Not surprising things get so exaggerated online, especially when it concerns the ever so popular arachnophobia. I doubt the average American eats more than a few spiders over their entire lifetime; your home simply shouldn’t be crawling with so many spiders that they end up in your mouth every night! A similar myth is still a myth but with a grain of truth – that earwigs burrow into your brain at night to lay eggs. It isn’t true that earwigs are human parasites (thankfully), but they do have a predisposition to crawl into tight, damp places. It is possible that this was a frequent enough occurrence in Ye Olde England that the earwig earned this notorious name. Cockroaches have also been documented as ear-spelunkers – but any crawly insect that might be walking on us at night could conceivably end up in one of our orifices.

I have however never heard of a moth crawling into an ear until I came across this story today! I guess a confused Noctuid somehow ended up in this boy’s ear, although I can’t help but to wonder if he put it there himself… Moths aren’t usually landing on people while they are asleep nor are they that prone to find damp, tight spots. But then again anything is possible, some noctuids do crawl under bark or leaves in the daytime for safe hiding. I even came across another story of an ear-moth form the UK (not that the Daily Mail is a reputable source).

Természetesen, some lazy news sources are using file photos of “lepkék” instead of copying the photo from the original story. It’s extra hilarious because one of the pictures used is of a new species of moth described last year by Bruce Walsh in Arizona. Lithophane leeae has been featured on my blog twice before, but never like this!

On a closing note here is a poem by Robert Cording (also where the above image was found).

Consider this: a moth flies into a man’s ear

One ordinary evening of unnoticed pleasures.

When the moth beats its wings, all the winds

Of earth gather in his ear, roar like nothing

He has ever heard. He shakes and shakes

His head, has his wife dig deep into his ear

With a Q-tip, but the roar will not cease.

It seems as if all the doors and windows

Of his house have blown away at once—

The strange play of circumstances over which

He never had control, but which he could ignore

Until the evening disappeared as if he had

Never lived it. His body no longer

Seems his own; he screams in pain to drown

Out the wind inside his ear, and curses God,

Who, hours ago, was a benign generalization

In a world going along well enough.

On the way to the hospital, his wife stops

The car, tells her husband to get out,

To sit in the grass. There are no car lights,

No streetlights, no moon. She takes

A flashlight from the glove compartment

And holds it beside his ear and, unbelievably,

The moth flies towards the light. His eyes

Are wet. He feels as if he’s suddenly a pilgrim

On the shore of an unexpected world.

When he lies back in the grass, he is a boy

Újra. His wife is shining the flashlight

Into the sky and there is only the silence

He has never heard, and the small road

Of light going somewhere he has never been.

– Robert Cording, Common Life: Poems (Fort Lee: CavanKerry Press, 2006), 29–30.

Chris Grinter, on June 30th, 2011

Micronecta scholtzi The hills of the European countryside are alive in the chorus of amorous, screaming, male aquatic bugs. The little insect above, Micronecta scholtzi (Corixidae), measures in at a whopping 2.3mm and yet produces a clicking/buzzing sound easily audible to the human ear above the water surface. To put that in perspective: trying to hear someone talk underwater while standing poolside is nearly impossible, yet this minute insect generates a click loud enough to be mistaken for a terrestrial arthropod. While that doesn’t sound too impressive when we are surrounded by other loud insects like the cicada, M. scholtzi turns out to be a stunningly loud animal when you take into consideration the body size and medium the sound is propagating through to reach our ear. Put into numbers the intensity of the clicks underwater can reach up to 100 dB (Sound Pressure Level, SPL). Shrink us into the insect world and this sound production is equal to a jackhammer at the same distance! So what on earth has allowed this little bug to make this noise and get away with it in a world full of predators?

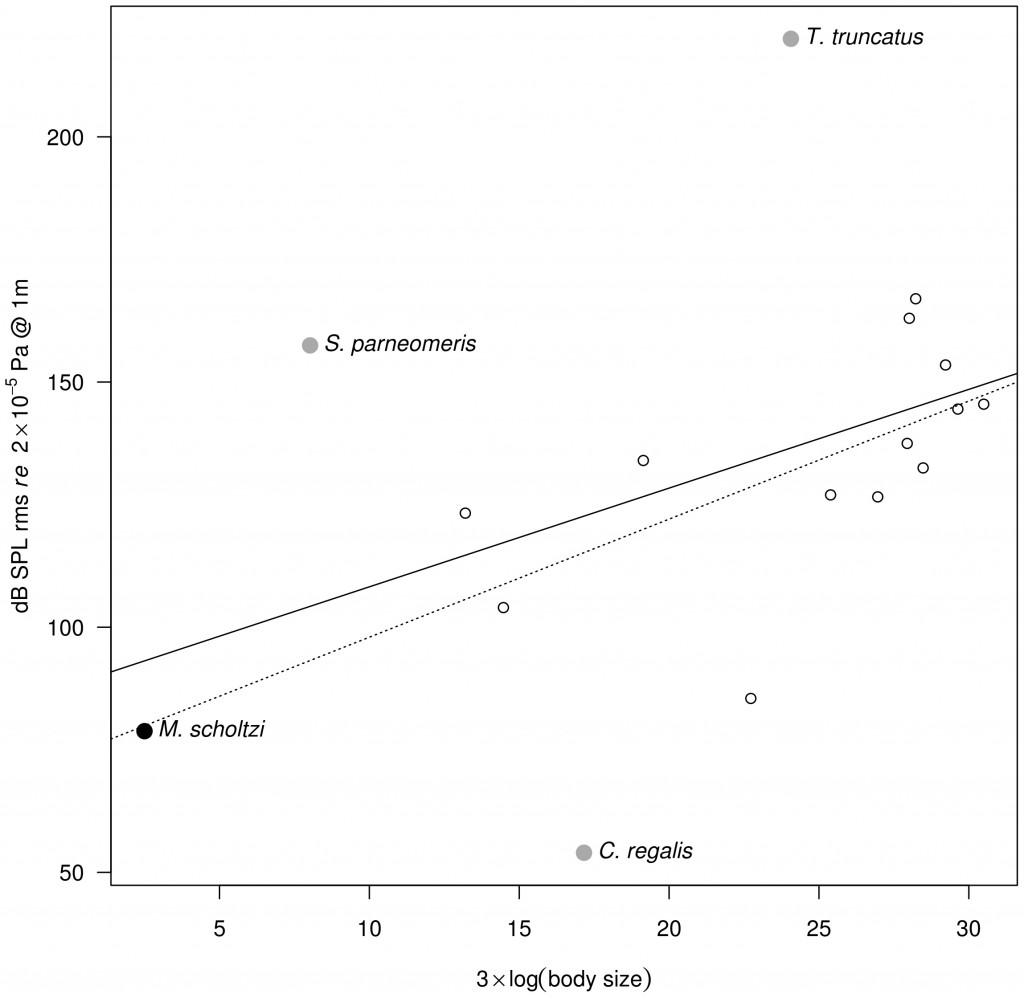

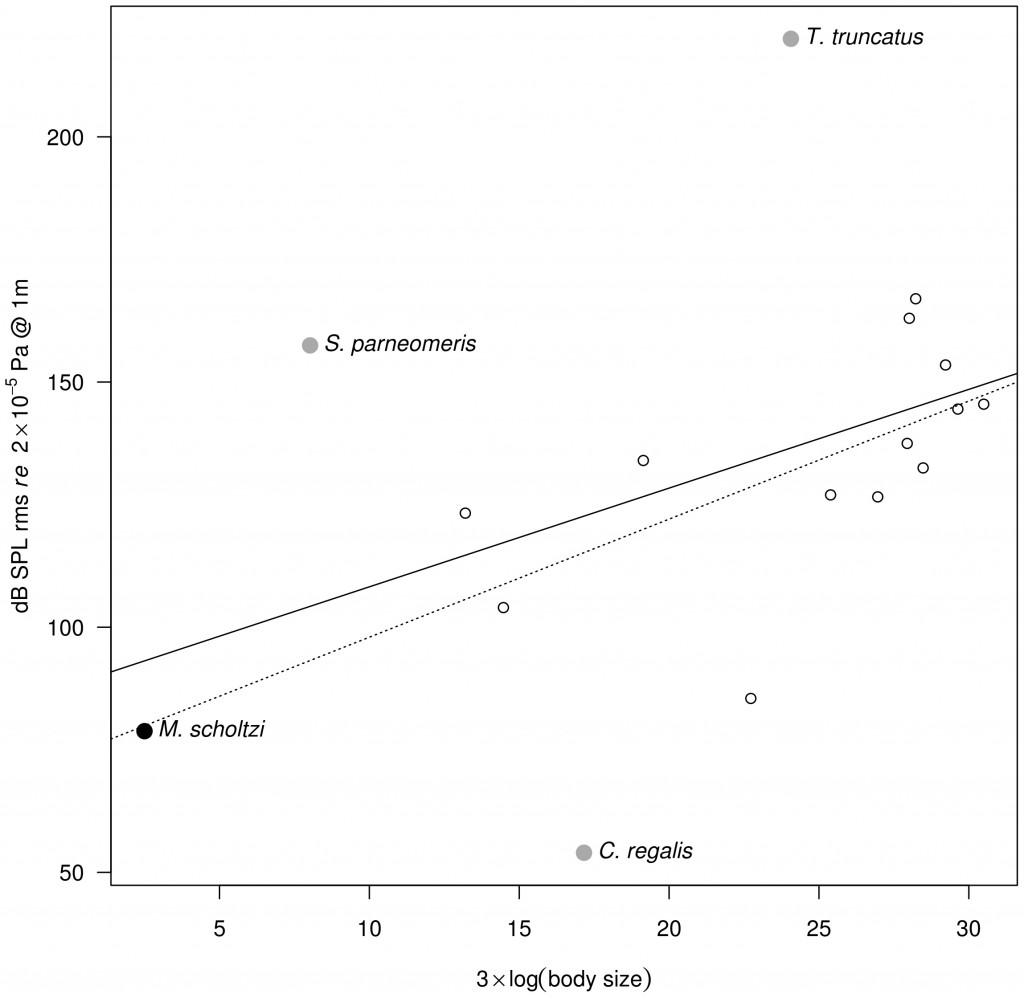

The authors naturally point out how surprising these results are. The first thing that becomes apparent is that the water boatmen must have no auditory predators since they are basically swimming around making the most noise physically possible for any small animal anywhere. Really this isn’t too surprising since most underwater predators are strictly visual hunters (dragonfly larvae, water bugs and beetles etc…). It is very likely that sexual selection has guided the development of these stridulatory calls into such astounding levels. The second most surprising thing is clear once you graph just how loud these insects are relative to their body size. At the top of the graph is the bottlenose dolphin (T. truncatus) with its famous sonar. But the greatest outlier is actually our little insect in the bottom left with the very highest ratio between sound and body size (31.5 with a mean of 6.9). No other known animal comes close. It is likely though that further examination of other aquatic insects may yield similar if not more surprising results!

To be more accurate about the “screaming”, the bugs (bugs in this instance is correct; the Corixidae belong to the order Hemiptera – the true bugs) are likely to be stridulating – rubbing together two parts to generate sound instead of exhaling air, drumming, stb.… In the article the authors speculate that the “sound is produced by rubbing a pars stridens on the right paramere (genitalia appendage) against a ridge on the left lobe of the eighth abdominal segment [15]”. Without pulling up their citation, it appears that stridulation by males in the genus is well documented for mate attraction. And as you would expect, news outlets and science journalists read “genitalia appendage” and translate that to penis: and you end up with stories like this. The function of the parameres can be loosely translated to similar to mandibles in that they are opposing structures (usually armed with hairs) for grasping. A exact use of them may differ by species or even orders, but they are very distinct form the penis (=aedeagus) since they simply help facilitate mating and don’t deliver any sperm. So in reality you have genital “claspers” with a “pars stridens”. And the best illustration of a pars stridens is over on the old blog Archetype. This structure is highlighted below in yellow (and happens to exist on the abdomen of the ant). De röviden – it’s a regular grooved surface akin to a washboard. In the end the sentence quoted above should be translated to “two structures at the tip of the abdomen that rub together like two fingers snapping”.

Detail of the pars stridens (in yellow) on the forth abdominal tergite in a Pachycondyla villosa worker (Scanning Electron Micrograph, Roberto Keller/AMNH) Continue reading The incredibly loud world of bug sex

Chris Grinter, június 20-án, 2011 Folyamatosan gurulok ezzel a sorozattal és megpróbálom rendszeresebbé tenni. Arra is összpontosítok, hogy minden héten új fajokat emeljek ki a kaliforniai Tudományos Akadémia hatalmas gyűjteményeiből. Ennek elegendő anyagot kell adnom… legalább néhány száz év.

Grammia edwardsii (Erebidae: Arctiinae) This week’s specimen is the tiger moth Grammia edwardsii. Up until a few years ago this family of moths was considered separate from the Noctuidae – but recent molecular and morphological analysis shows that it is in fact a Noctuid. The family Erebidae was pulled out from within the Noctuidae and the Arctiidae were placed therein, turning them into the subfamily Arctiinae. OK boring taxonomy out of the way – all in all, it’s a beautiful moth and almost nothing is known about it. This specimen was collected in San Francisco in 1904 – in fact almost all specimens known of this species were collected in the city around the turn of the century. While this moth looks very similar to the abundant and widespread Grammia ornata, close analysis of the eyes, wing shape and antennae maintain that this is actually a separate species. I believe the last specimen was collected around the 1920’s and it hasn’t been seen since. It is likely and unfortunate that this moth may have become extinct over the course of the last 100 years of development of the SF Bay region. Grammia, and Arctiinae in general, are not known for high levels of host specificity; they tend to be like little cows and feed on almost anything in their path. So it remains puzzling why this moth wouldn’t have habitat today, even in a city so heavily disturbed. Perhaps this moth specialized in the salt marsh areas surrounding the bay – which have all since been wiped out due to landfill for real-estate (1/3 of the entire bay was lost to fill). Or perhaps this moth remains with us even today but is never collected because it is an evasive day flying species. I always keep my eye out in the park in spring for a small orange blur…

|

Szkepticizmus

|