Di Chris Grinter, on July 25th, 2011 This Monday I am departing from the usual Arctiinae for something completely different – a microlep! This is a Nepticulidae, Stigmella diffasciae, and it measures in at a whopping 6 mm. I can’t take credit for spreading this moth – all of the nepticulids I have photographed are from the California Academy of Sciences and spread by Dave Wagner while he was here for a postdoctorate position.

The caterpillars mine the upper-side of the leaves of Ceanothus and are known only from the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California. If you’re so inclined the revision of the North American species of the genus is freely available here (.PDF).

Stigmella diffasciae (Nepticulidi)

Di Chris Grinter, il 22 Luglio, 2011 It’s been a little while since the last GOP challenge, ma this is a softball. I’m hoping they were just too lazy to find a more suitable image…

Di Chris Grinter, il 19 luglio, 2011 Cosa farebbe Gesù se avesse avuto un po 'di tempo libero – forse curare una malattia, terminare una guerra, o nutrire gli affamati – ma nah, tutti vedono che venendo. Perché non scioccare al nucleo – bruciare la faccia su una ricevuta Walmart! Almeno, that’s what a couple in South Carolina believe to have found, un Walmart receipt with Jesus’s face on it. This isn’t exactly new or exciting, humans have a wonderful ability to recognize a face in just about anything. Jesus and other characters “appear” on random things all the time, and even in 2005 a shrine was built to the Virgin Mary around a water stain in a Chicago underpass.

Pareidolia anyone? Effettivamente, that face looks pretty convincing, I’m not too sure this wasn’t just faked or “enhanced”. The closeups even look like there are fingerprints all over it. Since I don’t have a walmart anywhere near me or a walmart receipt on hand I can’t determine how sensitive the paper is and how easy it would have been to do – but how long do you think before it shows up on ebay? In ogni caso, it looks much more like James Randi to me than Jesus (at least we actually know what Randi looks like!).

from CNN

Di Chris Grinter, on July 18th, 2011 Over on Arthropoda, fellow SFS blogger Michael Bok shared an image of his field buddy, Plugg the green tree frog. My first thought was of a similar tree frog that haunted welcomed me everywhere I went in Santa Rosa National Park, Costarica. Needless to say, Costa Rica instills a sudden habit of double checking everything you are about to do. This species is known as the milk frog (Phrynohyas venulosa) for their copious amounts of milky white toxic secretions. One of the first stories Dan Janzen told me while while I was with him at Santa Rosa was about this species – and accidentally rubbing his eye after holding it. Thankfully the blindness and burning was only temporary.

Milk Frog: Phrynohyas venulosa

Di Chris Grinter, on July 18th, 2011 I’ll keep the ball rolling with Arctiinae and post a photo today of Ctenucha brunnea. This moth can be common in tall grasses along beaches from San Francisco to LA – although in recent decades the numbers of this moth have been declining with habitat destruction and the invasion of beach grass (Ammophila arenaria). But anywhere there are stands of giant ryegrass (Leymus condensatus) you should find dozens of these moths flying in the heat of the day or nectaring on toyon.

Ctenucha brunnea (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

Di Chris Grinter, on July 12th, 2011 Well as you may have guessed the subject isn’t as shocking as my title suggests, but I couldn’t help but to spin from the Guardian article. I really find it hilarious when I come across anything that says scientists are “astounded”, “baffled”, “shocked”, “puzzled”, – I guess that’s a topic for another time… Nevertheless a veramente cool butterfly has emerged at the “Sensational Butterflies” exhibit at the British Museum in London – un gynandromorph bilaterale! The Guardian reports today that this specimen of Papilio memnon just emerged and is beginning to draw small crowds of visitors. I know I’d love to see one of these alive again – although the zoo situation would take away quite a bit of the excitement. I think the only thing more exciting than seeing one of these live in the field would be to net one myself!

One little thing tripped my skeptical sensors and that is the quote at the end of the article taken from the curator of butterflies, Blanca Huertas. “The gynandromorph butterfly is a fascinating scientific phenomenon, and is the product of complex evolutionary processes. It is fantastic to have discovered one hatching on museum grounds, particularly as they are so rare.”

Bene, I don’t specifically see how these are a “product of … evolutionary processes” inasmuch as tutti life in tutti forms is a product of evolution. These are sterile “glitches” that are cool, but not anything that has been specifically evolved for or against. Perhaps it would be more adept to call this a fascinating process of genetics (which the article actually describes with accuracy). Anche – butterflies emerge as adults and hatch as caterpillars – but that’s just me being picky.

Di Chris Grinter, on July 11th, 2011 Today’s moth is a beautiful and rare species from SE Arizona and Mexico: Lerina incarnata (Erebidae: Arctiinae). Like many other day flying species it is brilliantly colored and quite likely aposematic. After all, the host plant is a milkweed and the caterpillar is just as stunning (sotto).

Lerina incarnata (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

This image of an old, spread specimen hardly does the animal justice, but one lucky photographer found a female ovipositing at the very top of a hill outside of Tucson, Arizona. While you’re at it go check out some of Philip’s other great photographs on SmugMug.

Lerina incarnata - Philip Kline, BugGuide As I mentioned above this moth also has an equally impressive caterpillar that feeds on Ascleapias linaria (pineneedle milkweed).

Di Chris Grinter, il 5 luglio, 2011

Sembra che ci sia una preponderanza di leggende metropolitane che coinvolgono gli insetti striscianti in faccia mentre dormiamo. Il più famoso mito è qualcosa sulla falsariga di “si mangia 8 ragni un anno durante il sonno“. In realtà quando si google che il numero varia da 4 a 8… fino a una libbra? Non cose sorprendenti ottenere così esagerati in linea, soprattutto quando riguarda il aracnofobia mai così popolare. Dubito le mangia americano medio più di un paio di ragni sopra il loro intero ciclo di vita; la vostra casa semplicemente non dovrebbe essere strisciando con tanti ragni che finiscono in bocca ogni notte! Un mito simile è ancora un mito, ma con un grano di verità – che forbicine scavano nel vostro cervello di notte per deporre le uova. Non è vero che forbicine sono parassiti umani (per fortuna), ma hanno una predisposizione a strisciare in stretto, luoghi umidi. E 'possibile che questo era un evento abbastanza frequente in Ye Olde Inghilterra che la earwig guadagnato questo nome famigerato. Gli scarafaggi sono stati documentati come auricolari speleologi – ma qualsiasi insetto crawly che potrebbero essere camminare su di noi durante la notte, concettualmente, potrebbe finire in uno dei nostri orifizi.

Ho però mai sentito parlare di una falena che striscia in un orecchio fino a quando mi sono imbattuto questa storia oggi! Credo che un Noctuid confuso in qualche modo finito all'orecchio di questo ragazzo, anche se non posso fare a meno di chiedersi se lo ha messo lì se stesso… Falene di solito non sono atterraggio sulle persone mentre dormono né sono che inclini a trovare smorzare, punti stretti. Ma poi di nuovo tutto è possibile, alcuni nottuidi non strisciare sotto corteccia o foglie di giorno per nascondiglio sicuro. Ho anche imbattuto un'altra storia di un orecchio-falena formare il Regno Unito (Non che il Daily Mail è una fonte affidabile).

Naturalmente, alcune fonti di notizie sono pigri usando le foto dei file di “falene” invece di copiare foto dalla storia originale. E 'divertente extra perché una delle immagini utilizzate è di una nuova specie di falena descritti lo scorso anno da Bruce Walsh in Arizona. Leeae litofania è stato descritto sul mio blog due volte prima, ma mai come questo!

Su una nota di chiusura ecco una poesia di Robert Cording (anche il luogo dove l'immagine qui sopra è stato trovato).

Considerate questo: una falena vola nell'orecchio di un uomo

Una sera ordinario di piaceri inosservati.

Quando la falena batte le ali, tutti i venti

Di terra riunire in un orecchio, ruggito come niente

Ha mai sentito parlare. Lui scuote e frullati

La sua testa, ha la moglie scavare in profondità nel suo orecchio

Con un Q-tip, ma il rombo non cesserà.

Sembra come se tutte le porte e le finestre

Della sua casa hanno spazzato via in una volta-

Lo strano gioco di circostanze sulle quali

Non ha mai avuto il controllo, ma che lui poteva ignorare

Fino alla sera scomparso come se avesse

Mai vissuta. Il suo corpo non è più

Sembra la sua; urla di dolore di annegare

Fuori il vento dentro il suo orecchio, e maledice Dio,

Chi, ore fa, era una generalizzazione benigna

In un mondo che va avanti abbastanza bene.

Sulla strada per l'ospedale, sua moglie si ferma

L'auto, dice il marito di uscire,

Per sedersi in erba. Non ci sono luci auto,

Nessun lampioni, senza luna. Prende

Una torcia elettrica del vano portaoggetti

E lo tiene accanto all'orecchio e, incredibilmente,

La falena vola verso la luce. I suoi occhi

Sono bagnato. Si sente come se fosse improvvisamente pellegrino

Sulla riva di un mondo inaspettato.

Quando dice il falso indietro nell'erba, lui è un ragazzo

Di nuovo. Sua moglie è brillante la torcia

Nel cielo e c'è solo il silenzio

Non ha mai sentito parlare, e la piccola strada

Di luce andando da qualche parte non è mai stato.

- Robert Cording, Vita Comune: Poesie (Forte Lee: Cavan Kerry Press, 2006), 29-30.

Di Chris Grinter, il 30 giugno, 2011

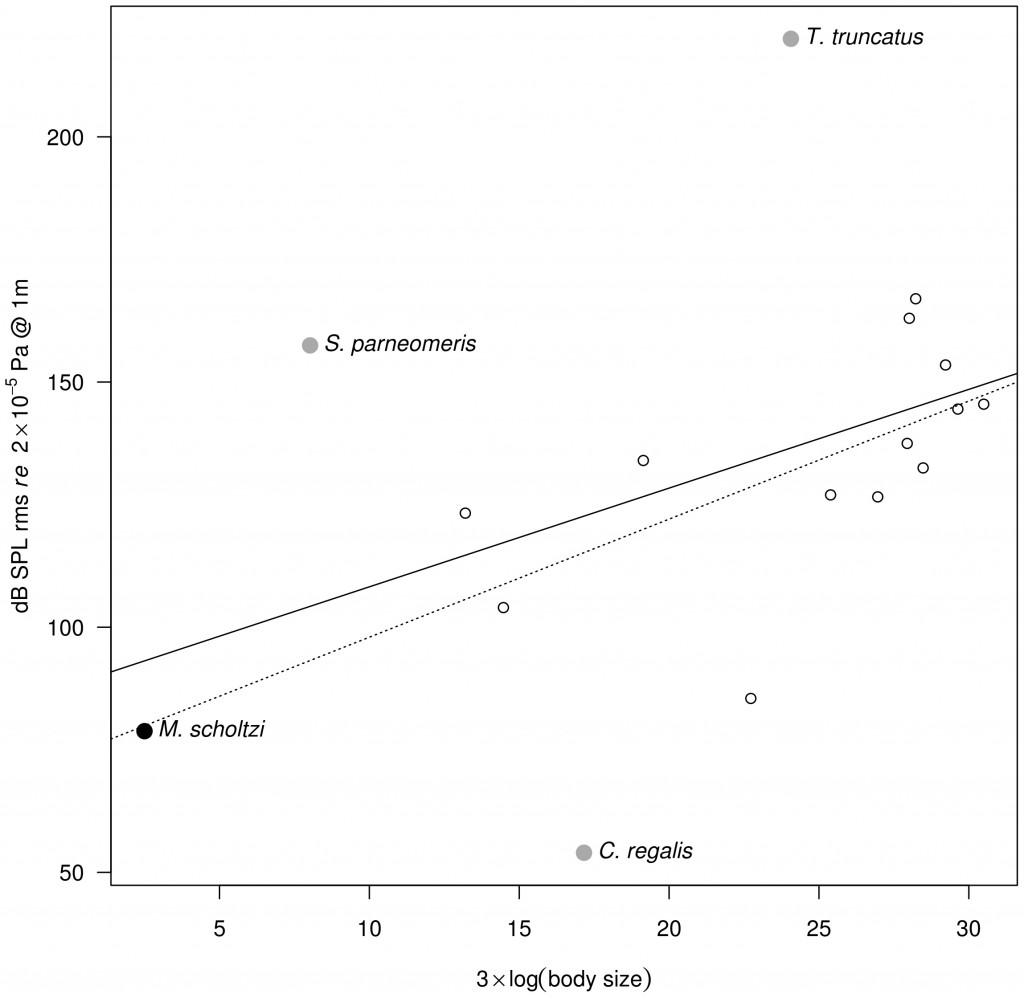

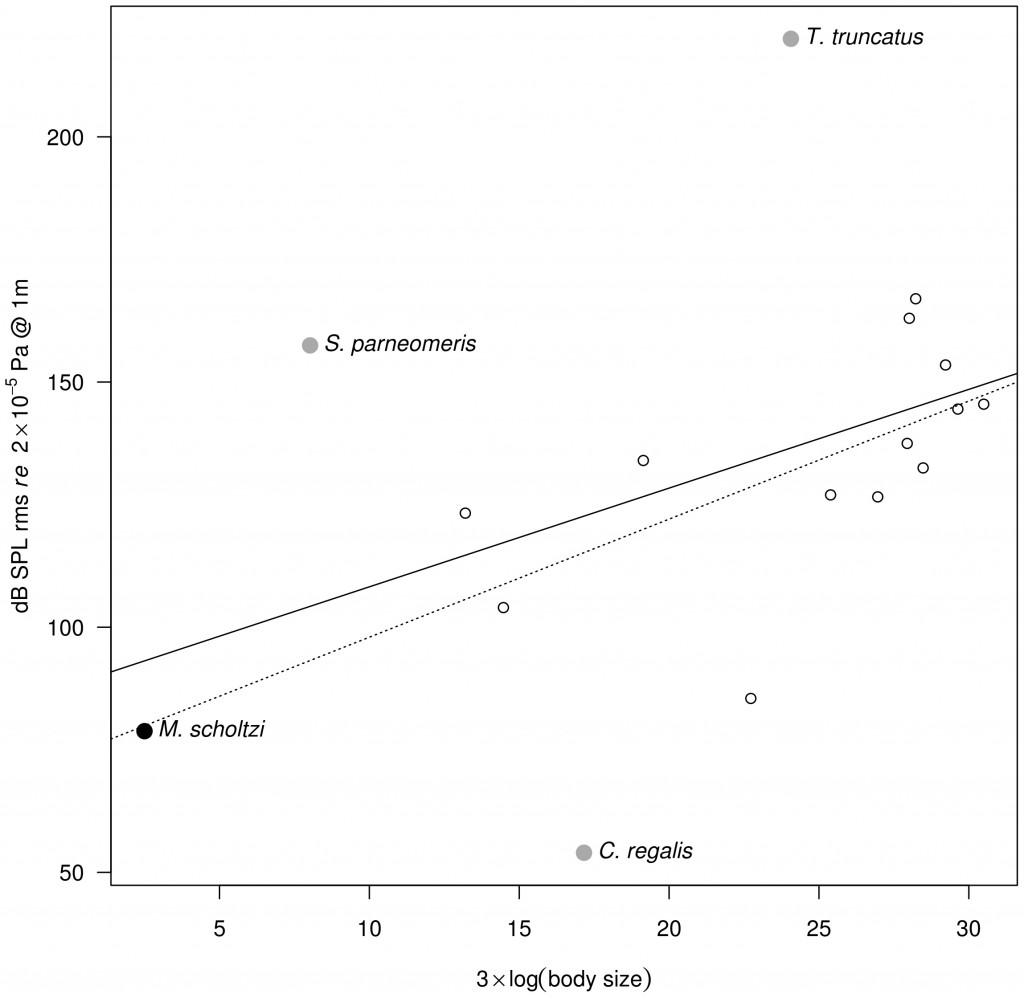

Micronecta Scholtz Le colline della campagna europea sono vivi nel coro di amorosa, urlando, insetti acquatici maschi. Il piccolo insetto sopra, Micronecta Scholtz (Corixidae), misura ben 2,3 mm e tuttavia produce facilmente un clic/ronzio udibile dall'uomo orecchio sopra la superficie dell'acqua. Per mettere che in prospettiva: provare a sentire qualcuno parlare sott'acqua mentre si sta a bordo piscina è quasi impossibile, eppure questo minuscolo insetto genera un clic abbastanza forte da essere scambiato per un artropode terrestre. Anche se ciò non sembra troppo impressionante quando siamo circondati da altri insetti rumorosi come la cicala, M. scöltzi risulta essere un animale incredibilmente rumoroso se si prendono in considerazione le dimensioni del corpo e il mezzo attraverso il quale il suono si propaga per raggiungere il nostro orecchio. Metti in numeri l'intensità dei clic sott'acqua che può raggiungere 100 dB (Livello di pressione sonora, SPL). Riduciamoci nel mondo degli insetti e questa produzione sonora è uguale a a martello pneumatico alla stessa distanza! Allora cosa diavolo ha permesso a questo piccolo insetto di fare questo rumore e farla franca in un mondo pieno di predatori??

Gli autori sottolineano naturalmente quanto siano sorprendenti questi risultati. La prima cosa che diventa evidente è che i barcaioli acquatici non devono avere predatori uditivi poiché praticamente nuotano in giro facendo il maggior rumore fisicamente possibile per qualsiasi piccolo animale ovunque.. In realtà questo non è troppo sorprendente poiché la maggior parte dei predatori sottomarini sono cacciatori esclusivamente visivi (larve di libellula, insetti acquatici e scarafaggi ecc…). È molto probabile che la selezione sessuale abbia guidato lo sviluppo di questi richiami stridulatori a livelli così sorprendenti. La seconda cosa più sorprendente è chiara una volta che si rappresenta graficamente quanto sono rumorosi questi insetti in relazione alle loro dimensioni corporee. Nella parte superiore del grafico c'è il delfino tursiope (T. troncato) con il suo famoso sonar. Ma l'anomalia più grande è in realtà il nostro piccolo insetto in basso a sinistra con il rapporto più alto tra suono e dimensioni del corpo (31.5 con una media di 6.9). Nessun altro animale conosciuto si avvicina a questo. È probabile, però, che ulteriori esami su altri insetti acquatici possano produrre risultati simili, se non addirittura più sorprendenti!

Per essere più precisi riguardo a “urlando”, gli insetti (bug in questo caso è corretto; i Corixidae appartengono all'ordine degli Emitteri – i veri bug) probabilmente strideranno – strofinando insieme due parti per generare il suono invece di espirare l'aria, percussione, eccetera… Nell'articolo gli autori ipotizzano che il “il suono viene prodotto sfregando una pars stridens sul paramere destro (appendice genitale) contro una cresta sul lobo sinistro dell'ottavo segmento addominale [15]”. Senza tirare fuori la loro citazione, sembra che la stridulazione da parte dei maschi del genere sia ben documentata per l'attrazione del compagno. E come ti aspetteresti, leggono i notiziari e i giornalisti scientifici “appendice genitale” e tradurlo in pene: e alla fine ti ritrovi con le storie come questo. La funzione dei parameri può essere liberamente tradotta in simile alle mandibole in quanto sono strutture opposte (solitamente armati di peli) per afferrare. Il il loro utilizzo esatto potrebbe differire per specie o anche per ordini, ma sono molto distinti dal pene (=edeago) poiché aiutano semplicemente a facilitare l'accoppiamento e non forniscono sperma. Quindi in realtà hai i genitali “fermagli” con un “la parte che strilla”. E la migliore illustrazione della pars stridens è sul vecchio blog Archetipo. Questa struttura è evidenziata di seguito in giallo (e sembra esistere sull'addome della formica). Ma in breve – è una superficie scanalata regolare simile a un asse per lavare. Alla fine la frase sopra citata dovrebbe essere tradotta in “due strutture sulla punta dell'addome che si sfregano insieme come se si schioccassero due dita”.

Particolare della pars stridens (in giallo) sul quarto tergite addominale in un'operaia di Pachycondyla villosa (Micrografia elettronica a scansione, Roberto Keller/AMNH) Continue reading The incredibly loud world of bug sex

Di Chris Grinter, on June 20th, 2011 I’m going to keep the ball rolling with this series and try to make it more regular. I will also focus on highlighting a new species each week from the massive collections here at the California Academy of Sciences. This should give me enough material for… at least a few hundred years.

Grammia edwardsii (Erebidae: Arctiinae) This week’s specimen is the tiger moth Grammia edwardsii. Up until a few years ago this family of moths was considered separate from the Noctuidae – but recent molecular and morphological analysis shows that it is in fact a Noctuid. The family Erebidae was pulled out from within the Noctuidae and the Arctiidae were placed therein, turning them into the subfamily Arctiinae. OK boring taxonomy out of the way – all in all, it’s a beautiful moth and almost nothing is known about it. This specimen was collected in San Francisco in 1904 – in fact almost all specimens known of this species were collected in the city around the turn of the century. While this moth looks very similar to the abundant and widespread Grammia ornata, close analysis of the eyes, wing shape and antennae maintain that this is actually a separate species. I believe the last specimen was collected around the 1920’s and it hasn’t been seen since. It is likely and unfortunate that this moth may have become extinct over the course of the last 100 years of development of the SF Bay region. Grammia, and Arctiinae in general, are not known for high levels of host specificity; they tend to be like little cows and feed on almost anything in their path. So it remains puzzling why this moth wouldn’t have habitat today, even in a city so heavily disturbed. Perhaps this moth specialized in the salt marsh areas surrounding the bay – which have all since been wiped out due to landfill for real-estate (1/3 of the entire bay was lost to fill). Or perhaps this moth remains with us even today but is never collected because it is an evasive day flying species. I always keep my eye out in the park in spring for a small orange blur…

|

Scetticismo

|