Door Chris Grinter, on July 25th, 2011 This Monday I am departing from the usual Arctiinae for something completely different – a microlep! This is a Nepticulidae, Stigmella diffasciae, and it measures in at a whopping 6 mm. I can’t take credit for spreading this moth – all of the nepticulids I have photographed are from the California Academy of Sciences and spread by Dave Wagner while he was here for a postdoctorate position.

The caterpillars mine the upper-side of the leaves of Ceanothus and are known only from the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California. If you’re so inclined the revision of the North American species of the genus is freely available here (.pdf).

Stigmella diffasciae (Nepticulidae)

Door Chris Grinter, op 22 juli, 2011 It’s been a little while since the last GOP challenge, maar this is a softball. I’m hoping they were just too lazy to find a more suitable image…

Door Chris Grinter, op 19 juli, 2011 Wat zou Jezus doen als hij wat vrije tijd gehad – misschien genezen van een ziekte, uiteindelijk een oorlog, of voeden de hongerende – maar nah, iedereen ziet dat de komende. Waarom ze niet shockeren om de kern – branden van uw gezicht op een Walmart ontvangst! Tenminste, dat is wat een stel in South Carolina denkt te hebben gevonden, een Walmart-bon met het gezicht van Jezus erop. Dit is niet bepaald nieuw of opwindend, mensen hebben een geweldig vermogen om in bijna alles een gezicht te herkennen. Jezus en andere personages “tevoorschijn komen” altijd over willekeurige dingen, en zelfs in 2005 een heiligdom werd gebouwd om de Maagd Maria rond a watervlek in een onderdoorgang van Chicago.

Pareidolie iedereen? Werkelijk, dat gezicht ziet er behoorlijk overtuigend uit, Ik ben er niet zo zeker van dat dit niet gewoon nep was of “versterkt”. De close-ups zien er zelfs uit alsof er overal vingerafdrukken op zitten. Aangezien ik nergens in de buurt een Walmart of een Walmart-bon bij de hand heb, kan ik niet bepalen hoe gevoelig het papier is en hoe gemakkelijk het zou zijn geweest om te doen – maar hoe lang denk je voordat het op ebay verschijnt?? In ieder geval, het lijkt veel meer op James Randi voor mij dan Jezus (wij tenminste eigenlijk weten hoe Randi eruit ziet!).

van CNN

Door Chris Grinter, on July 18th, 2011 Over op Arthropoda, collega SFS-blogger Michael Bok deelde een afbeelding van zijn veldmaatje, Sluit de groene boomkikker aan. Mijn eerste gedachte was van een soortgelijke boomkikker die behekst verwelkomde me overal waar ik ging in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. Onnodig te zeggen, Costa Rica wekt een plotselinge gewoonte op om alles wat je gaat doen dubbel te controleren. Deze soort staat bekend als de melkkikker (Phrynohyas venulosa) vanwege hun overvloedige hoeveelheden melkachtige witte giftige afscheidingen. Een van de eerste verhalen die Dan Janzen me vertelde toen ik bij hem in Santa Rosa was, ging over deze soort – en per ongeluk in zijn oog wrijft nadat hij het heeft vastgehouden. Gelukkig de blindheid en branden was maar tijdelijk.

Melk kikker: Phrynohyas venulosa

Door Chris Grinter, on July 18th, 2011 I’ll keep the ball rolling with Arctiinae and post a photo today of Ctenucha brunnea. This moth can be common in tall grasses along beaches from San Francisco to LA – although in recent decades the numbers of this moth have been declining with habitat destruction and the invasion of beach grass (Ammophila arenaria). But anywhere there are stands of giant ryegrass (Leymus condensatus) you should find dozens of these moths flying in the heat of the day or nectaring on toyon.

Ctenucha brunnea (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

Door Chris Grinter, on July 12th, 2011 Well as you may have guessed the subject isn’t as shocking as my title suggests, but I couldn’t help but to spin from the Guardian article. I really find it hilarious when I come across anything that says scientists are “astounded”, “baffled”, “shocked”, “puzzled”, – I guess that’s a topic for another time… Nevertheless a echt cool butterfly has emerged at the “Sensational Butterflies” exhibit at the British Museum in London – een bilaterale gynandromorf imago! The Guardian reports today that this specimen of Papilio memnon just emerged and is beginning to draw small crowds of visitors. I know I’d love to see one of these alive again – although the zoo situation would take away quite a bit of the excitement. I think the only thing more exciting than seeing one of these live in the field would be to net one myself!

One little thing tripped my skeptical sensors and that is the quote at the end of the article taken from the curator of butterflies, Blanca Huertas. “The gynandromorph butterfly is a fascinating scientific phenomenon, and is the product of complex evolutionary processes. It is fantastic to have discovered one hatching on museum grounds, particularly as they are so rare.”

Goed, I don’t specifically see how these are a “product of … evolutionary processes” inasmuch as all life in all forms is a product of evolution. These are sterile “glitches” that are cool, but not anything that has been specifically evolved for or against. Perhaps it would be more adept to call this a fascinating process of genetics (which the article actually describes with accuracy). Ook – butterflies emerge as adults and hatch as caterpillars – but that’s just me being picky.

Door Chris Grinter, op 11 juli, 2011 De mot van vandaag is een mooie en zeldzame soort uit Zuidoost-Arizona en Mexico: Lerina incarnata (Erebidae: Arctiinae). Net als veel andere dagvliegsoorten is hij schitterend gekleurd en hoogstwaarschijnlijk aposematisch. Ten slotte, de waardplant is een kroontjeskruid en de rups is net zo prachtig (onder).

Lerina incarnata (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

Deze afbeelding van een oude, verspreid exemplaar doet het dier nauwelijks recht, maar één gelukkige fotograaf vond een vrouwelijke oviposit op de top van een heuvel buiten Tucson, Arizona. Terwijl je toch bezig bent, ga je kijken naar enkele van Philip's andere geweldige foto's op SmugMug.

Lerina incarnata - Philip Kline, BugGuide Zoals ik hierboven al zei, heeft deze mot ook een even indrukwekkende rups die zich voedt met Ascleapias linaria (dennenaald kroontjeskruid).

Door Chris Grinter, op 5 juli, 2011

Het lijkt erop dat er een overwicht is aan stedelijke legendes waarin insecten in ons gezicht kruipen terwijl we slapen. De beroemdste mythe is iets in de trant van “jij eet 8 spinnen per jaar tijdens het slapen“. Als je googled, varieert het nummer eigenlijk van 4 tot 8… tot een pond? Het is niet verrassend dat dingen online zo overdreven worden, vooral als het de immer zo populaire arachnofobie betreft. Ik betwijfel of de gemiddelde Amerikaan gedurende zijn hele leven meer dan een paar spinnen eet; je huis zou gewoon niet vol moeten zitten met zoveel spinnen dat ze elke nacht in je mond terechtkomen! Een soortgelijke mythe is nog steeds een mythe, maar met een kern van waarheid – dat oorwormen zich 's nachts in je hersenen nestelen om eieren te leggen. Het is niet waar dat oorwormen menselijke parasieten zijn (gelukkig), maar ze hebben wel de neiging om in krappe ruimtes te kruipen, vochtige plaatsen. Het is mogelijk dat dit in Nederland vaak genoeg voorkwam Ye Olde Engeland dat de oorworm deze beruchte naam verdiende. Kakkerlakken zijn ook gedocumenteerd als oor-spelunkers – maar elk kruipend insect dat 's nachts over ons heen loopt, kan mogelijk in een van onze openingen terechtkomen.

Ik heb echter nog nooit gehoord van een mot die in een oor kruipt totdat ik hem tegenkwam dit verhaal vandaag! Ik vermoed dat er op de een of andere manier een verwarde Noctuid in het oor van deze jongen terecht is gekomen, al vraag ik me af of hij het daar zelf heeft neergezet… Motten landen meestal niet op mensen terwijl ze slapen, en ze zijn ook niet zo gevoelig voor vocht, krappe plekken. Maar ja, alles is mogelijk, sommige noctuïden kruipen overdag onder schors of bladeren om zich veilig te verstoppen. Kwam ik zelfs tegen nog een verhaal van een oormot uit Groot-Brittannië (niet dat de Daily Mail een betrouwbare bron is).

Natuurlijk, sommige luie nieuwsbronnen zijn dat wel met behulp van bestandsfoto's van “motten” in plaats van de foto uit het originele verhaal te kopiëren. Het is extra hilarisch omdat een van de gebruikte foto’s een nieuwe beschreven soort nachtvlinder is vorig jaar door Bruce Walsh in Arizona. Lithophane leeae is al twee keer eerder op mijn blog verschenen, maar nooit zo!

Ter afsluiting staat hier een gedicht van Robert Cording (ook waar de bovenstaande afbeelding werd gevonden).

Overweeg dit: een mot vliegt in het oor van een man

Een gewone avond vol onopgemerkte genoegens.

Als de mot met zijn vleugels slaat, alle winden

Er komt aarde in zijn oor, brullen als niets

Hij heeft het ooit gehoord. Hij schudt en schudt

Zijn hoofd, laat zijn vrouw diep in zijn oor graven

Met een wattenstaafje, maar het gebrul zal niet ophouden.

Het lijkt alsof alle deuren en ramen

Van zijn huis is in één keer weggeblazen -

Het vreemde spel van omstandigheden waarover

Hij heeft nooit controle gehad, maar die hij kon negeren

Totdat de avond verdween alsof hij dat had gedaan

Heb het nooit geleefd. Zijn lichaam niet meer

Lijkt van hemzelf; hij schreeuwt van de pijn dat hij moet verdrinken

Uit de wind in zijn oor, en vervloekt God,

WHO, uur geleden, was een goedaardige generalisatie

In een wereld die goed genoeg draait.

Op weg naar het ziekenhuis, zijn vrouw stopt

De auto, zegt tegen haar man dat hij weg moet gaan,

Om in het gras te zitten. Er zijn geen autolichten,

Geen straatverlichting, geen maan. Ze neemt

Een zaklamp uit het dashboardkastje

En houdt het naast zijn oor en, ongelooflijk,

De mot vliegt naar het licht. Zijn ogen

Zijn nat. Het voelt alsof hij plotseling een pelgrim is

Aan de oever van een onverwachte wereld.

Als hij weer in het gras ligt, hij is een jongen

Nog een keer. Zijn vrouw schijnt met de zaklamp

De lucht in en daar is alleen de stilte

Hij heeft het nog nooit gehoord, en de kleine weg

Van licht dat ergens naartoe gaat waar hij nog nooit is geweest.

– Robert Cording, Gemeenschappelijk leven: Gedichten (Fort Lee: CavanKerry Press, 2006), 29–30.

Door Chris Grinter, op 30 juni, 2011

Micronecta scholtzi De heuvels van het Europese platteland leven in het koor van amoureuze mensen, schreeuwen, mannelijke waterwantsen. Het kleine insect hierboven, Micronecta scholtzi (Corixidae), measures in at a whopping 2.3mm and yet produces a clicking/buzzing sound easily audible to the human ear above the water surface. To put that in perspective: trying to hear someone talk underwater while standing poolside is nearly impossible, yet this minute insect generates a click loud enough to be mistaken for a terrestrial arthropod. While that doesn’t sound too impressive when we are surrounded by other loud insects like the cicada, M. scholtzi turns out to be a stunningly loud animal when you take into consideration the body size and medium the sound is propagating through to reach our ear. Put into numbers the intensity of the clicks underwater can reach up to 100 dB (Sound Pressure Level, SPL). Shrink us into the insect world and this sound production is equal to a jackhammer at the same distance! So what on earth has allowed this little bug to make this noise and get away with it in a world full of predators?

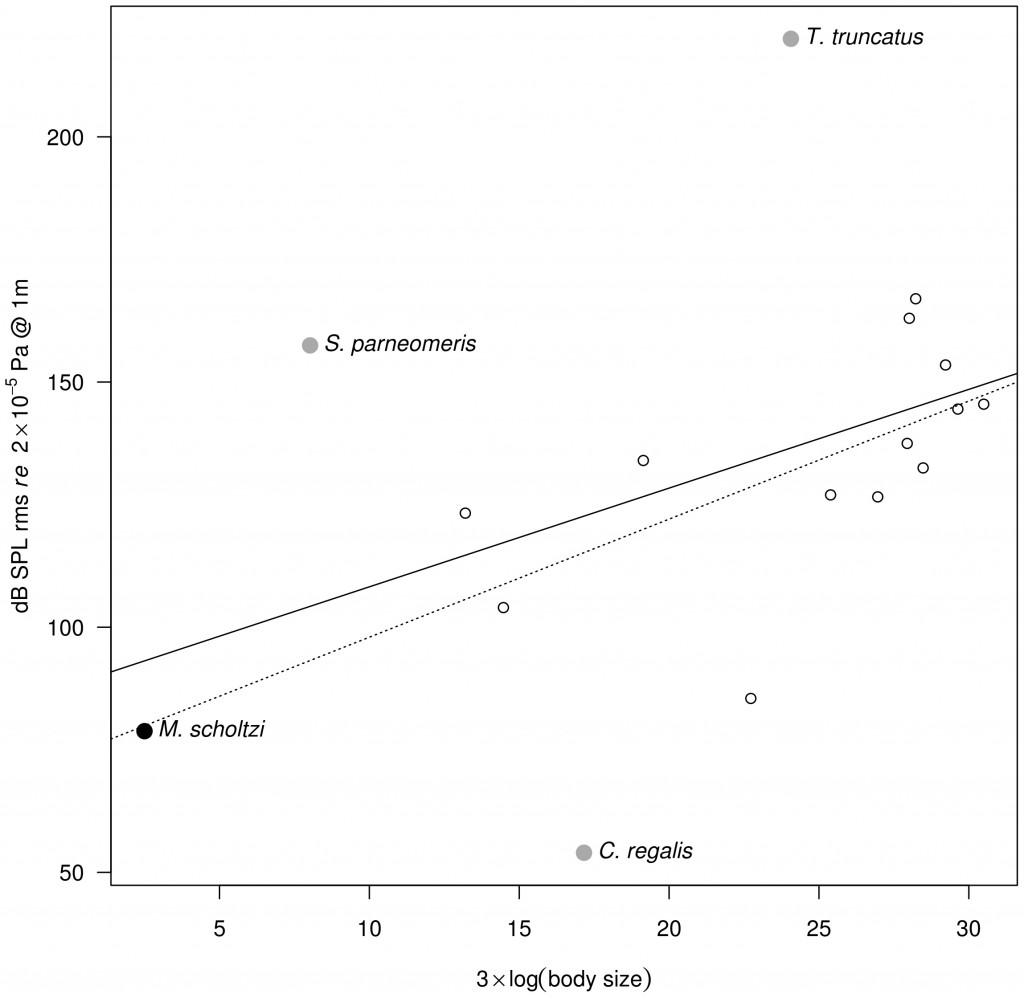

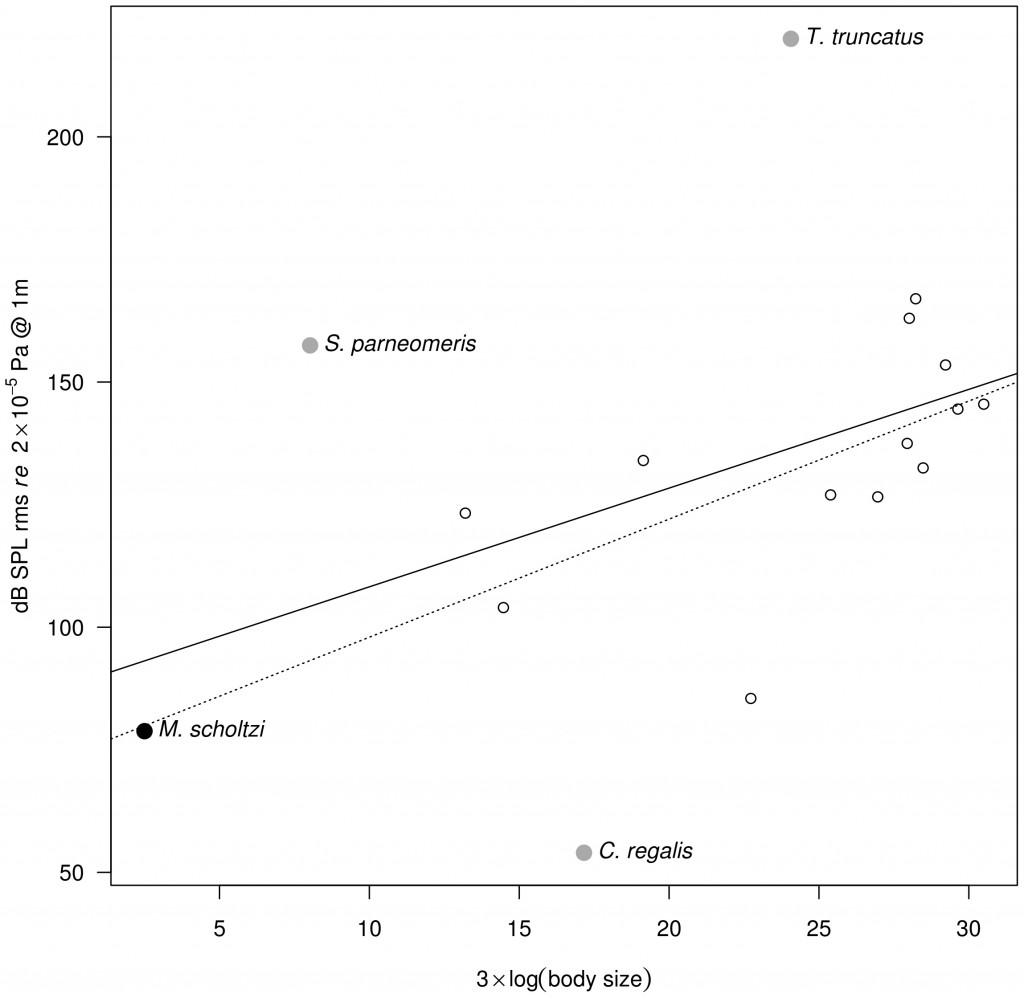

The authors naturally point out how surprising these results are. The first thing that becomes apparent is that the water boatmen must have no auditory predators since they are basically swimming around making the most noise physically possible for any small animal anywhere. Really this isn’t too surprising since most underwater predators are strictly visual hunters (dragonfly larvae, water bugs and beetles etc…). It is very likely that sexual selection has guided the development of these stridulatory calls into such astounding levels. The second most surprising thing is clear once you graph just how loud these insects are relative to their body size. At the top of the graph is the bottlenose dolphin (T. truncatus) with its famous sonar. But the greatest outlier is actually our little insect in the bottom left with the very highest ratio between sound and body size (31.5 with a mean of 6.9). No other known animal comes close. It is likely though that further examination of other aquatic insects may yield similar if not more surprising results!

To be more accurate about the “schreeuwen”, the bugs (bugs in this instance is correct; the Corixidae belong to the order Hemiptera – the true bugs) are likely to be stridulating – rubbing together two parts to generate sound instead of exhaling air, drumming, etc.… In the article the authors speculate that the “sound is produced by rubbing a pars stridens on the right paramere (genitalia appendage) against a ridge on the left lobe of the eighth abdominal segment [15]”. Without pulling up their citation, it appears that stridulation by males in the genus is well documented for mate attraction. And as you would expect, news outlets and science journalists read “genitalia appendage” and translate that to penis: and you end up with stories like this. The function of the parameres can be loosely translated to similar to mandibles in that they are opposing structures (usually armed with hairs) for grasping. Het exact use of them may differ by species or even orders, but they are very distinct form the penis (=aedeagus) since they simply help facilitate mating and don’t deliver any sperm. So in reality you have genital “claspers” with a “pars stridens”. And the best illustration of a pars stridens is over on the old blog Archetype. This structure is highlighted below in yellow (and happens to exist on the abdomen of the ant). But in short – it’s a regular grooved surface akin to a washboard. In the end the sentence quoted above should be translated to “two structures at the tip of the abdomen that rub together like two fingers snapping”.

Detail of the pars stridens (in yellow) on the forth abdominal tergite in a Pachycondyla villosa worker (Scanning Electron Micrograph, Roberto Keller/AMNH) Continue reading The incredibly loud world of bug sex

Door Chris Grinter, on June 20th, 2011 Ik ga de bal aan het rollen houden met deze serie en proberen het regelmatiger te maken. Ik zal me ook concentreren op het uitlichten van elke week een nieuwe soort uit de enorme collecties hier in de California Academy of Sciences. Dit zou me genoeg materiaal moeten geven voor… minstens een paar honderd jaar.

Grammia edwardsii (Erebidae: Arctiinae) Het exemplaar van deze week is de tijgermot Grammia edwardsii. Tot een paar jaar geleden werd deze familie van motten als apart beschouwd van de Noctuidae – maar recente moleculaire en morfologische analyse toont aan dat het in feite een Noctuid is. De familie Erebidae werd uit de Noctuidae getrokken en de Arctiidae werden daarin geplaatst, ze veranderen in de onderfamilie Arctiinae. OK saaie taxonomie uit de weg – globaal genomen, het is een prachtige nachtvlinder en er is bijna niets over bekend. Dit exemplaar is verzameld in San Francisco in 1904 – in feite zijn bijna alle bekende exemplaren van deze soort rond de eeuwwisseling in de stad verzameld. Hoewel deze mot erg lijkt op de overvloedige en wijdverspreide Sierlijke Grammy, nauwkeurige analyse van de ogen, vleugelvorm en antennes beweren dat dit eigenlijk een aparte soort is. Ik geloof dat het laatste exemplaar rond 1920 werd verzameld en sindsdien niet meer is gezien. Het is waarschijnlijk en jammer dat deze mot in de loop van de afgelopen tijd is uitgestorven 100 jarenlange ontwikkeling van de SF Bay-regio. Grammia, en Arctiinae in het algemeen, staan niet bekend om hun hoge gastheerspecificiteit; ze hebben de neiging om als kleine koeien te zijn en voeden zich met bijna alles op hun pad. Het blijft dus een raadsel waarom deze mot vandaag geen leefgebied zou hebben, zelfs in een stad die zo zwaar gestoord is. Misschien specialiseerde deze mot zich in de kweldergebieden rond de baai – die sindsdien allemaal zijn weggevaagd als gevolg van stortplaatsen voor onroerend goed (1/3 van de hele baai was verloren om te vullen). Of misschien blijft deze mot zelfs vandaag bij ons, maar wordt nooit verzameld omdat het een ontwijkende dagvliegsoort is. Ik kijk in het voorjaar altijd in het park naar een kleine oranje waas…

|

Scepticisme

|