Por Chris Grinter, on July 25th, 2011 This Monday I am departing from the usual Arctiinae for something completely different – a microlep! This is a Nepticulidae, Stigmella diffasciae, and it measures in at a whopping 6 milímetros. I can’t take credit for spreading this moth – all of the nepticulids I have photographed are from the California Academy of Sciences and spread by Dave Wagner while he was here for a postdoctorate position.

The caterpillars mine the upper-side of the leaves of Ceanothus and are known only from the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California. If you’re so inclined the revision of the North American species of the genus is freely available here (.pdf).

Stigmella diffasciae (Nepticulidae)

Por Chris Grinter, em 22 de julho, 2011 It’s been a little while since the last GOP challenge, mas this is a softball. I’m hoping they were just too lazy to find a more suitable image…

Por Chris Grinter, on July 19th, 2011 What would Jesus do if he had some free time – maybe cure a disease, end a war, or feed the starving – but nah, everyone sees that coming. Why not shock them to the core – burn your face on a Walmart receipt! Pelo menos, that’s what a couple in South Carolina believe to have found, uma Walmart receipt with Jesus’s face on it. This isn’t exactly new or exciting, humans have a wonderful ability to recognize a face in just about anything. Jesus and other characters “appear” on random things all the time, and even in 2005 a shrine was built to the Virgin Mary around a water stain in a Chicago underpass.

Pareidolia anyone? Na realidade, that face looks pretty convincing, I’m not too sure this wasn’t just faked or “enhanced”. The closeups even look like there are fingerprints all over it. Since I don’t have a walmart anywhere near me or a walmart receipt on hand I can’t determine how sensitive the paper is and how easy it would have been to do – but how long do you think before it shows up on ebay? Em qualquer evento, it looks much more like James Randi to me than Jesus (at least we actually know what Randi looks like!).

from CNN

Por Chris Grinter, em 18 de julho, 2011 Over on Arthropoda, fellow SFS blogger Michael Bok shared an image of his field buddy, Plugg the green tree frog. My first thought was of a similar tree frog that haunted welcomed me everywhere I went in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. Needless to say, Costa Rica instills a sudden habit of double checking everything you are about to do. This species is known as the milk frog (Phrynohyas venulosa) for their copious amounts of milky white toxic secretions. One of the first stories Dan Janzen told me while while I was with him at Santa Rosa was about this species – and accidentally rubbing his eye after holding it. Thankfully the blindness and burning was only temporary.

Milk Frog: Phrynohyas venulosa

Por Chris Grinter, em 18 de julho, 2011 Vou manter a bola rolando com Arctiinae e postar uma foto hoje de Ctenucha Brunnea. Esta mariposa pode ser comum em gramíneas altas ao longo das praias de São Francisco a Los Angeles – embora nas últimas décadas os números desta mariposa tenham diminuído com a destruição do habitat e a invasão de grama de praia (Ammophila arenaria). Mas em qualquer lugar há plantações de azevém gigante (Leymus condensatus) você deve encontrar dezenas dessas mariposas voando no calor do dia ou nectar em toyon.

Ctenucha Brunnea (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

Por Chris Grinter, on July 12th, 2011 Well as you may have guessed the subject isn’t as shocking as my title suggests, but I couldn’t help but to spin from the Guardian article. I really find it hilarious when I come across anything that says scientists are “astounded”, “baffled”, “shocked”, “puzzled”, – I guess that’s a topic for another time… Nevertheless a realmente cool butterfly has emerged at the “Sensational Butterflies” exhibit at the British Museum in London – um gynandromorph bilateral! The Guardian reports today that this specimen of Papilio memnon just emerged and is beginning to draw small crowds of visitors. I know I’d love to see one of these alive again – although the zoo situation would take away quite a bit of the excitement. I think the only thing more exciting than seeing one of these live in the field would be to net one myself!

One little thing tripped my skeptical sensors and that is the quote at the end of the article taken from the curator of butterflies, Blanca Huertas. “The gynandromorph butterfly is a fascinating scientific phenomenon, and is the product of complex evolutionary processes. It is fantastic to have discovered one hatching on museum grounds, particularly as they are so rare.”

Bem, I don’t specifically see how these are a “product of … evolutionary processes” inasmuch as tudo life in tudo forms is a product of evolution. These are sterile “glitches” that are cool, but not anything that has been specifically evolved for or against. Perhaps it would be more adept to call this a fascinating process of genetics (which the article actually describes with accuracy). Também – butterflies emerge as adults and hatch as caterpillars – but that’s just me being picky.

Por Chris Grinter, em 11 de julho, 2011 A mariposa de hoje é uma espécie bonita e rara do sudeste do Arizona e do México: Lerina encarnada (Erebidae: Arctiinae). Como muitas outras espécies voadoras diurnas, é brilhantemente colorida e provavelmente aposemática. Afinal, a planta hospedeira é uma serralha e a lagarta é tão impressionante quanto (abaixo).

Lerina encarnada (Erebidae: Arctiinae)

Esta imagem de um velho, espécime espalhado dificilmente faz justiça ao animal, mas um fotógrafo de sorte encontrou uma fêmea ovipositando no topo de uma colina fora de Tucson, Arizona. Enquanto você está nisso, confira algumas das outras ótimas fotografias de Philip no SmugMug.

Lerina encarnada - Philip Kline, BugGuide Como mencionei acima, esta mariposa também tem uma lagarta igualmente impressionante que se alimenta de Ascleápias linaria (serralha de pinheiro).

Por Chris Grinter, em 05 de julho, 2011

Parece que há uma preponderância de lendas urbanas que envolvem insetos rastejando em nossos rostos enquanto dormimos. O mito mais famoso é algo ao longo das linhas de “você come 8 aranhas por ano durante o sono“. Na verdade, quando você procurar no google que o número varia de 4 a 8… up to a pound? Not surprising things get so exaggerated online, especially when it concerns the ever so popular arachnophobia. I doubt the average American eats more than a few spiders over their entire lifetime; your home simply shouldn’t be crawling with so many spiders that they end up in your mouth every night! A similar myth is still a myth but with a grain of truth – that earwigs burrow into your brain at night to lay eggs. It isn’t true that earwigs are human parasites (thankfully), but they do have a predisposition to crawl into tight, damp places. It is possible that this was a frequent enough occurrence in Ye Olde England that the earwig earned this notorious name. Cockroaches have also been documented as ear-spelunkers – but any crawly insect that might be walking on us at night could conceivably end up in one of our orifices.

I have however never heard of a moth crawling into an ear until I came across this story today! I guess a confused Noctuid somehow ended up in this boy’s ear, although I can’t help but to wonder if he put it there himself… Moths aren’t usually landing on people while they are asleep nor are they that prone to find damp, tight spots. But then again anything is possible, some noctuids do crawl under bark or leaves in the daytime for safe hiding. I even came across another story of an ear-moth form the UK (not that the Daily Mail is a reputable source).

Naturalmente, some lazy news sources are using file photos of “moths” instead of copying the photo from the original story. It’s extra hilarious because one of the pictures used is of a new species of moth described last year by Bruce Walsh in Arizona. Litofano Leeae has been featured on my blog twice before, but never like this!

On a closing note here is a poem by Robert Cording (also where the above image was found).

Consider this: a moth flies into a man’s ear

One ordinary evening of unnoticed pleasures.

When the moth beats its wings, all the winds

Of earth gather in his ear, roar like nothing

He has ever heard. He shakes and shakes

His head, has his wife dig deep into his ear

With a Q-tip, but the roar will not cease.

It seems as if all the doors and windows

Of his house have blown away at once—

The strange play of circumstances over which

He never had control, but which he could ignore

Until the evening disappeared as if he had

Never lived it. His body no longer

Seems his own; he screams in pain to drown

Out the wind inside his ear, and curses God,

Who, hours ago, was a benign generalization

In a world going along well enough.

On the way to the hospital, his wife stops

The car, tells her husband to get out,

To sit in the grass. There are no car lights,

No streetlights, no moon. She takes

A flashlight from the glove compartment

And holds it beside his ear and, unbelievably,

The moth flies towards the light. His eyes

Are wet. He feels as if he’s suddenly a pilgrim

On the shore of an unexpected world.

When he lies back in the grass, he is a boy

Será um prazer enviar uma foto se precisar. His wife is shining the flashlight

Into the sky and there is only the silence

He has never heard, and the small road

Of light going somewhere he has never been.

– Robert Cording, Common Life: Poems (Fort Lee: CavanKerry Press, 2006), 29–30.

Por Chris Grinter, em 30 de junho, 2011

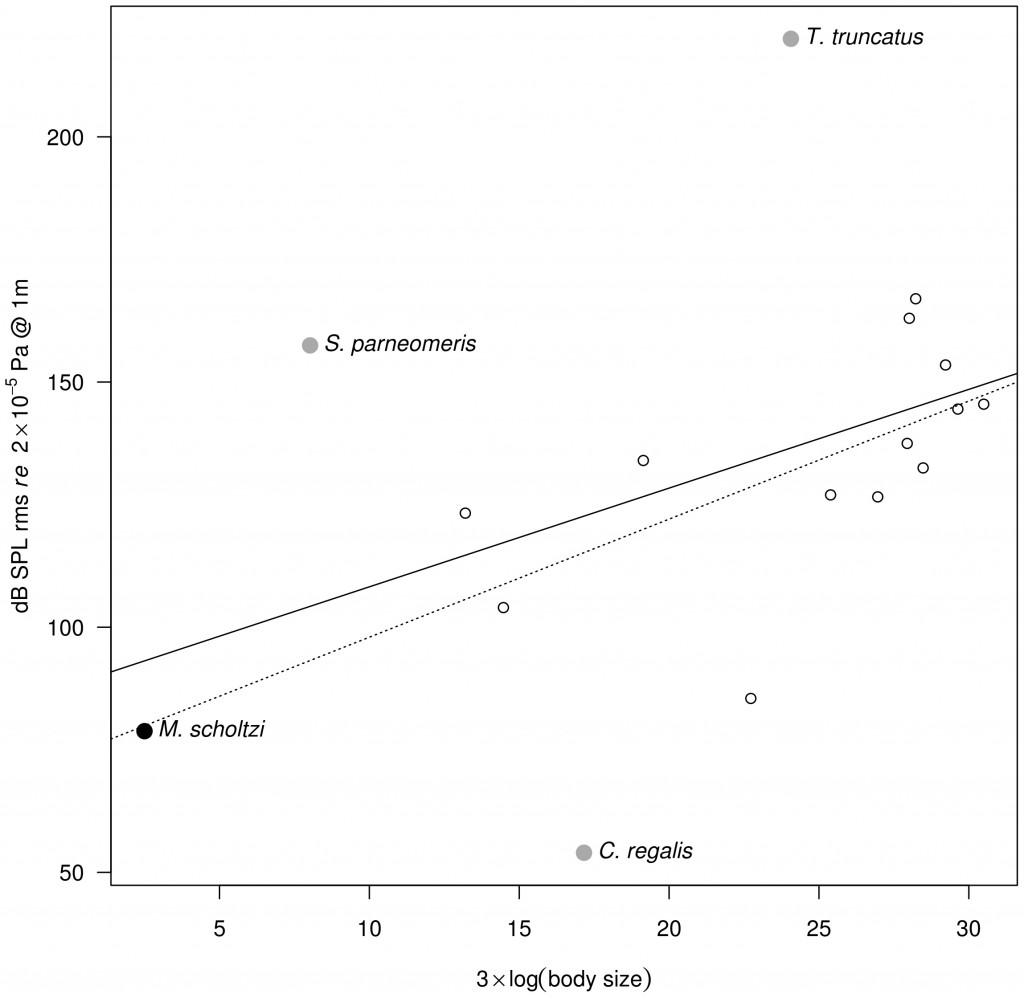

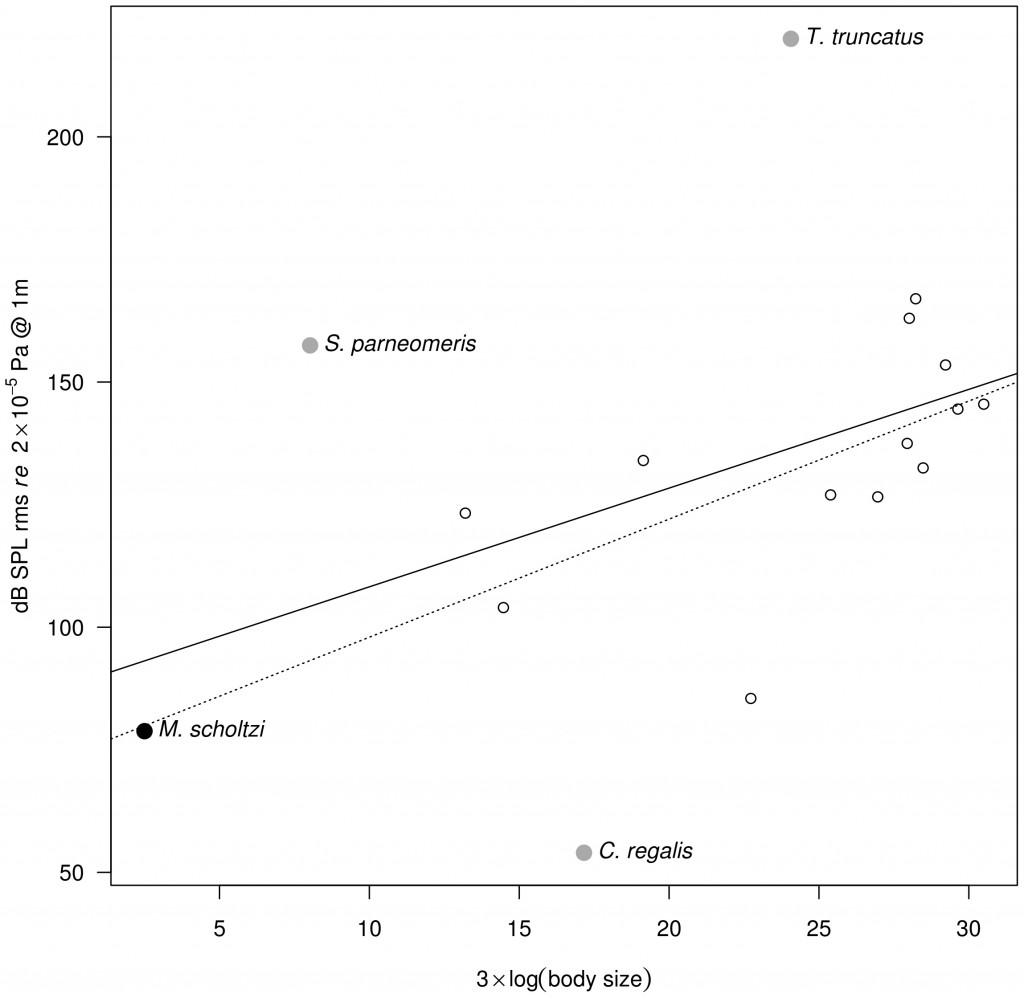

Micronecta scholtzi As colinas da paisagem europeia estão vivos no coro das amorosa, gritando, insetos aquáticos do sexo masculino. O pequeno inseto acima, Micronecta scholtzi (Corixidae), mede 2,3 mm e ainda produz um som de clique/zumbido facilmente audível para o humano orelha acima da superfície da água. Para colocar isso em perspectiva: tentar ouvir alguém falar debaixo d'água enquanto está ao lado da piscina é quase impossível, no entanto, este minúsculo inseto gera um clique alto o suficiente para ser confundido com um artrópode terrestre. Embora isso não pareça muito impressionante quando estamos cercados por outros insetos barulhentos como a cigarra, M. Scholtzi acaba sendo um animal incrivelmente barulhento quando você leva em consideração o tamanho do corpo e o meio pelo qual o som está se propagando para chegar ao nosso ouvido. Colocando em números, a intensidade dos cliques debaixo d'água pode chegar a 100 dB (Nível de pressão sonora, SPL). Reduza-nos para o mundo dos insetos e esta produção de som é igual a um britadeira na mesma distância! Então, o que permitiu que esse pequeno inseto fizesse esse barulho e escapasse impune em um mundo cheio de predadores??

Os autores naturalmente apontam o quão surpreendentes são esses resultados. A primeira coisa que se torna aparente é que os barqueiros não devem ter predadores auditivos, pois estão basicamente nadando, fazendo o máximo de barulho fisicamente possível para qualquer pequeno animal em qualquer lugar.. Realmente, isso não é muito surpreendente, já que a maioria dos predadores subaquáticos são caçadores estritamente visuais. (larvas de libélula, insetos aquáticos e besouros etc…). É muito provável que a seleção sexual tenha guiado o desenvolvimento desses chamados estridulários a níveis tão surpreendentes. A segunda coisa mais surpreendente fica clara quando você faz um gráfico de quão barulhentos esses insetos são em relação ao tamanho do corpo.. No topo do gráfico está o golfinho nariz-de-garrafa (T. truncado) com seu famoso sonar. Mas o maior outlier é, na verdade, nosso pequeno inseto no canto inferior esquerdo com a maior proporção entre som e tamanho do corpo. (31.5 com uma média de 6.9). Nenhum outro animal conhecido chega perto. É provável, porém, que um exame mais aprofundado de outros insetos aquáticos possa produzir resultados semelhantes, se não mais surpreendentes.!

Para ser mais preciso sobre o “gritando”, Os insetos (bugs neste caso está correto; os Corixidae pertencem à ordem Hemiptera – os verdadeiros erros) são susceptíveis de estar estridulando – esfregando duas partes para gerar som em vez de exalar o ar, tocar bateria, etc… No artigo, os autores especulam que o “o som é produzido esfregando um pars stridens no parâmetro direito (apêndice da genitália) contra uma crista no lobo esquerdo do oitavo segmento abdominal [15]”. Sem puxar sua citação, parece que a estridulação por machos do gênero está bem documentada para atração de parceiros. E como você esperaria, agências de notícias e jornalistas científicos leem “apêndice da genitália” e traduza isso para pênis: e você acaba com histórias como isso. A função dos parâmeros pode ser vagamente traduzida como semelhante às mandíbulas, pois são estruturas opostas (geralmente armado com cabelos) para agarrar. O o uso exato deles pode diferir por espécies ou mesmo ordens, mas eles são muito distintos do pênis (=edeago) uma vez que eles simplesmente ajudam a facilitar o acasalamento e não entregam nenhum esperma. Então, na realidade, você tem genitais “fechos” com um “a parte que grita”. E a melhor ilustração de pars stridens está no arquétipo de blog antigo. Esta estrutura é destacada abaixo em amarelo (e passa a existir no abdômen da formiga). Mas resumindo – é uma superfície ranhurada regular semelhante a uma tábua de lavar. Ao final, a frase citada acima deve ser traduzida para “duas estruturas na ponta do abdômen que se esfregam como dois dedos estalando”.

Detalhe dos pars stridens (em amarelo) no quarto tergito abdominal em uma operária Pachycondyla villosa (Micrografia Eletrônica de Varredura, Roberto Keller/AMNH) Continue reading The incredibly loud world of bug sex

Por Chris Grinter, em 20 de junho, 2011 Vou manter a bola rolar com esta série e tentar torná-lo mais regular. Eu também vai se concentrar em destacar uma nova espécie a cada semana a partir das imensas coleções aqui na Academia de Ciências da Califórnia. Isso deve dar-me material suficiente para… pelo menos algumas centenas de anos.

Grammia edwardsii (Erebidae: Arctiinae) This week’s specimen is the tiger moth Grammia edwardsii. Up until a few years ago this family of moths was considered separate from the Noctuidae – but recent molecular and morphological analysis shows that it is in fact a Noctuid. The family Erebidae was pulled out from within the Noctuidae and the Arctiidae were placed therein, turning them into the subfamily Arctiinae. OK boring taxonomy out of the way – all in all, it’s a beautiful moth and almost nothing is known about it. This specimen was collected in San Francisco in 1904 – in fact almost all specimens known of this species were collected in the city around the turn of the century. While this moth looks very similar to the abundant and widespread Grammia ornata, close analysis of the eyes, wing shape and antennae maintain that this is actually a separate species. I believe the last specimen was collected around the 1920’s and it hasn’t been seen since. It is likely and unfortunate that this moth may have become extinct over the course of the last 100 years of development of the SF Bay region. Grammia, and Arctiinae in general, are not known for high levels of host specificity; they tend to be like little cows and feed on almost anything in their path. So it remains puzzling why this moth wouldn’t have habitat today, even in a city so heavily disturbed. Perhaps this moth specialized in the salt marsh areas surrounding the bay – which have all since been wiped out due to landfill for real-estate (1/3 of the entire bay was lost to fill). Or perhaps this moth remains with us even today but is never collected because it is an evasive day flying species. I always keep my eye out in the park in spring for a small orange blur…

|

Ceticismo

|